It’s as much about an old dictator trying to keep his replacement out of power.

By Laura Kasinof

On Sunday, Secretary of State John Kerry, along with his British counterpart, Boris Johnson, called for an immediate cease-fire to the war in Yemen. A U.S. Navy ship had fired missiles into Yemen on Thursday, directed at the Houthi rebels controlling the northern half of the country, in response to attacks on U.S. ships in the Red Sea.

Saudi Arabia’s leadership said it would agree to the cease-fire if the Houthis, who have yet to respond, did so as well. (Update, Oct. 18: The U.N. announced Tuesday morning that the Houthis have agreed to a temporary cease-fire, starting Thursday.) But the U.S. is apparently not too keen on continuing its mission creep. We have been providing intelligence and logistical support to Saudi Arabia since it began its assault on Yemen in March 2015 in response to the Houthis taking control of the government. It’s a conflict that generates less attention than Syria yet has nonetheless brought much humanitarian disaster.

The war in Yemen has left at least 10,000 dead, including almost 4,000 civilians, according to the United Nations, and has displaced 3.2 million Yemenis, out of a population of 27 million. It has decimated the economy of what was already the poorest country in the Arab world and sparked a deadly famine. Yemen’s infrastructure is in ruins.

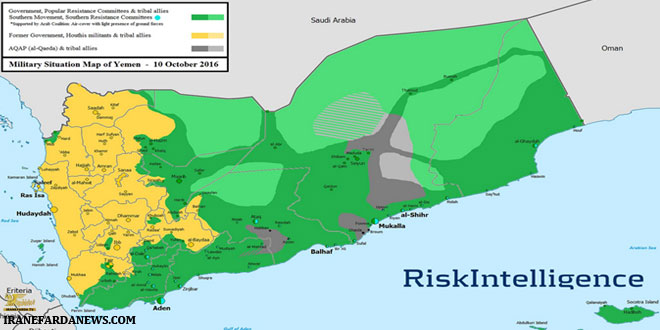

Saudi Arabia’s official reason for continuing its assault on its impoverished southern neighbor is to restore the legitimate president of the country, Abd-Rabbu Mansour Hadi, which is also the U.S.’s excuse for supporting the war. Hadi fled the capital, Sanaa, in February 2015 and now stays in Saudi Arabia. But Saudi Arabia accuses Iran of backing the Houthis, and the war in Yemen is often cast as a proxy battle between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

That portrayal is understandable, given that Iran and the Houthis share ideological affinities. But that description doesn’t do justice to the situation on the ground. The war in Yemen is more of an ongoing domestic power struggle that has spiraled out of control and was exacerbated by the political upheaval of the Arab Spring. When outside countries became involved militarily, Yemen was wedged into the pressure cooker of Middle East geopolitics, making it even harder to reach a modicum of peace. (Tuesday’s announcement of a cease-fire is promising, but unfortunately, cease-fires have come and gone over the past 20 months, and Yemen’s political mess that instigated the war remains unresolved.)

The Houthis and Iranians are both Shiites, though the Houthis are Zaydis, a different branch of Shiite Islam than is practiced by Iranian leadership. Indeed, the Iranian government did work to increase its influence in Yemen after the change in Yemeni leadership in 2012 by supporting activists who were against Hadi’s government. Saudi Arabia was keenly aware of such developments, and the monarchy, fearful of Shiite Islam as it is, did not want Iran to gain any more allies in the region, especially not on its southern border. Yet Yemen analysts agree that Saudi Arabia blew the extent to which Iran supported the Houthis out of proportion. Whether that was an intentional calculation or not, it laid the groundwork for a war against an enemy that would not be as easily defeated as the Saudis had initially planned. Much like the Soviets were pulled into an ongoing, unwinnable war against the mujahedeen in Afghanistan, and the U.S. repeating that mistake in Iraq decades later, the Houthis and their allies are entrenched in northern Yemen, and thus far, no amount of Saudi bombing has changed that.

Earlier this month, for example Saudi Arabia bombed the funeral party of one of northern Yemen’s prominent sheikhs, the traditional tribal leaders who still hold much sway in the country. The attack killed at least 140 civilians, among them moderate leaders who could have played a role in mediating for a peaceful future. Meanwhile, the Houthis are engaged in a bitter battle with their domestic foes (who are being supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), in other Yemeni cities, primarily Taiz. Everywhere, civilians suffer as result, and hospitals can’t keep up with the carnage.

* * *

After the Arab Spring–inspired protests in 2011, Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had ruled Yemen for 33 years, handed over power to his once impotent deputy, Hadi, in February 2012. The breakdown of Saleh’s government paved the way for rebel movements such as the Houthis, who’d been engaged in an on-again, off-again conflict with the government for more than a decade. Islamists were another such group, though that category described everyone from al-Qaida supporters to moderate members of Yemen’s Muslim Brotherhood. The Houthis, who are best thought of as a tribal militia, were longtime rivals with the tribal militias supported by Islamist leaders, and conflict arose between the two sides in Yemen’s rural areas as soon as Saleh stepped down as president.

Hadi, lacking any traditional base of support because his power came almost solely from the U.N. and Western powers that supported him, cozied up to the Islamists. The Houthis fought this all the way to capital, which they took in September 2014, chasing out the failed and weak President Hadi.

In order to do so and to push the Islamists further south, the Houthis partnered, very critically, with their old nemesis, Saleh.

Saleh, who was a corrupt and bloody dictator, had stayed in the country with immunity after stepping down, part of the transition deal that was brokered by the Western powers and their Gulf allies. The importance of this Saleh-Houthi alliance cannot be overstated. Saleh, who is much more affable and well-liked in the north than Hadi, had old, powerful allies in the capital who felt defeated under Hadi’s presidency. Saleh’s allies overnight became fans of the Houthis because it was a way of being anti-Hadi. It was a way of getting their country back after the Arab Spring when the Islamists gained more power. As for Saleh, working with his old foes, the Houthis, was not surprising. The wily former leader had long been a master of playing all sides to benefit his rule, and the Houthis were a tool for him to slip right back into a leadership position. The Saudi bombing campaign has only helped his cause by cementing popular support for the Houthi-Saleh alliance in the capital. The U.S. support for that campaign has only increased anti-American sentiment.

The Houthis’ precise political goals are unclear and have been since the beginning of their rebellion in 2003. What Saleh wants is not vague. He wants Hadi not to be president, and in this way the war in Yemen is really a clash of personalities: Saleh on one side with the Houthis behind him, and on the other is not only Hadi but old political leaders who have had riffs with Saleh, including the Saudi monarchy. They are all fighting over the right to control Yemen, but Yemen is being destroyed in the process. The country is fractured with two de-facto capitals, Sanaa and the southern port city Aden, out of which Hadi’s government functions.

It seems that Saudi Arabia has resigned to try to smoke out the rebels in control of Sanaa. If northern Yemen is desperate and starving enough, maybe Saleh and the Houthis will concede. Yet so far, the Houthi-Saleh alliance has only dug in further because, true to any war of personalities, it has become a matter of pride.

During a recent chat, a friend from Yemen told me that the only way out of this mess for Yemen is for a hero to step in. A Yemeni leader who has legitimacy on all sides, who has no problems with Saleh or the Islamists or southerners. This is a distinctly Yemeni solution, and to the surprise of many, conflict mediation is actually something in which Yemeni tribes have a history of success. However, the tragic part is that too much damage may have been done to ever reach such an agreement.

Laura Kasinof was the Yemen correspondent for the New York Times from 2011–12 and the author of the reporting memoir Don’t Be Afraid of the Bullets: An Accidental War Correspondent in Yemen. She lives in Berlin.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community