By Steve Everly June 23, 2016

Fearing a Russian invasion, the U.S. and Britain were prepared to ravage the region’s oil industry—and even considered going nuclear.

On a cool summer day in London in 1951, an American CIA officer told three British oil executives about a top-secret U.S. government plan. The goal was to ravage the Middle East oil industry if the region were ever invaded by the Soviet Union. Oil wells would be plugged, equipment and fuel stockpiles destroyed, refineries and pipelines disabled—anything to keep the USSR from getting its hands on valuable oil resources. The CIA called it the “denial policy.”

Such a plan couldn’t work without the cooperation of the British and American companies who controlled the oil industry in the Middle East, which is why the CIA operative, George Prussing, ended up at the Ministry of Fuel and Power in London that day. To the British representatives of Iraq Petroleum, Kuwait Oil and Bahrain Oil, Prussing detailed how their production operations in those countries would in effect be transformed into a paramilitary force, trained and ready to execute the CIA’s plan in the event of a Soviet invasion. He asked for their help, and they agreed to cooperate. He also emphasized the need for security, which included keeping the policy secret from the targeted Middle East countries. “Security now is more important than the success of any operations,” Prussing told them.

The CIA’s oil denial policy is a snippet of a Cold War history that is finally giving up more of its secrets. In 1996, a brief description of the plan emerged after the Truman Presidential Library mistakenly declassified it—a security breach the National Archives deemed the worst in its history—and some additional details have trickled out over the years. But a recently discovered trove of documents stashed in Britain’s National Archives, along with some key American documents, now declassified, provide a more complete and more revelatory account—published here for the first time.

It turns out that the denial policy, long believed to have ended during Eisenhower’s presidency, was in place much longer than that, lingering into the Kennedy administration. And the newly discovered British documents reveal Britain was prepared to use nuclear weapons to keep the Soviet Union from Middle Eastern oil. The documents also show that the CIA played a far larger role than previously thought. The State Department and the National Security Council were always known to have been significantly involved, but in fact, it was the intelligence agency that was the driving force of the operation, organizing American and British companies to execute the denial policy, coming up with plans, providing explosives and spying on some of those companies as part of its oversight.

The history of this top secret U.S. government plot is a tumultuous mix of Arab nationalism, Big Oil and the CIA on the most oil-rich chunk of real estate on earth. Fundamentally, it is a tale of the growing importance of Middle Eastern oil and the West’s early thirst to control it. And decades later, with that thirst still driving U.S. involvement in the volatile region, it’s worth remembering the risky scheme that foreshadowed it all.

The oil denial policy was hatched in 1948 during the Berlin Blockade, when the Soviet Union tried to block the West’s access to the German city. The blockade stoked fears that further communist aggression would include a sweep through Iran and Iraq to the Persian Gulf—an invasion, the Truman administration worried, that U.S. troops and their allies wouldn’t be able to stop. But American and British companies controlled Middle Eastern oil, and the U.S. government decided a stop-gap measure could stymie the Soviet military by ensuring its taste for fuel wasn’t slaked with petroleum.

The National Security Council’s plan, officially known as NSC 26/2 (and which was approved by President Harry Truman in 1949), was for those American and British companies to destroy or sideline Middle East oil resources and facilities at the start of a Soviet offensive. According to the NSC 26/2 planning documents, the State Department would provide oversight; the CIA would handle the operational details for each country.

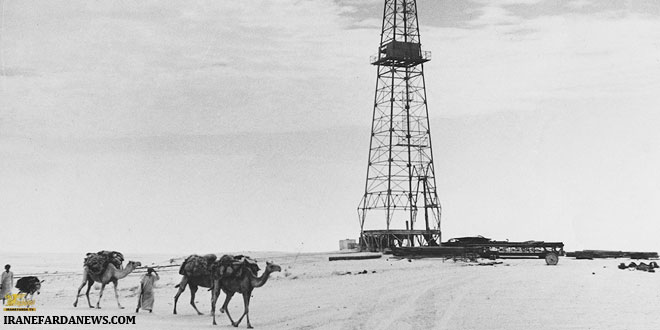

Aramco adds another stretch to the company’s thousand of miles of pipelines in Saudi Arabia in 1951. This section will carry oil from the wells to refineries

Based on National Security Council documents, the intelligence agency immediately approached Terry Duce, Aramco’s vice president of government relations, for advice about implementing a covert denial plan in Saudi Arabia. Aramco owned the rights to produce Saudi Arabian oil and had a working relationship with the country’s government. Duce, who liked to wear a black beret and loved the spy game, had served a stint at the federal government’s Petroleum Administration during World War II and was well known in Washington. Allen Dulles, who later became the CIA’s director, was a frequent guest at Duce’s home.

Aramco, jointly owned at the time by predecessor companies of Exxon Corp., Mobil Inc., Chevron Corp. and Texaco Inc., threw itself into the effort by providing the CIA with crucial advice, including how to plug oil wells and disable refineries. Through Duce, Aramco also volunteered its employees to execute the plan and was even willing to consider their induction into the military if the plan were triggered. (Aramco and U.S. officials hoped military status would protect employees from execution for sabotage if they were captured.)

In the meantime, according to British Foreign Office documents, the British government was notified about NSC 26/2 and threw its support behind the measure, agreeing to prepare denial plans for its oil companies in Iran and Iraq. Britain’s approach differed from the outset: While the CIA’s strategy for Saudi Arabia relied entirely on Aramco employees and not at all on the U.S. military, the British plan used airborne troops to protect and assist the hundreds of oil company employees who would participate in destroying the facilities.

All appeared to be going well for the CIA’s ambitious plot. But it wasn’t long until this promising start began to degenerate. British oil companies turned out to be way more reluctant to cooperate than their government had been. In late 1950, Sir Thomas Fraser, chairman of Anglo-Iranian Oil Co., a jewel in the fading British Empire, learned for the first time his company was expected to provide hundreds of employees for the denial scheme. He feared economic blackmail, even expulsion, if the Iranian government learned about his company’s involvement—and, according to British documents, Fraser pulled Anglo-Iranian Oil out of the plan in late 1950.

George McGhee, an undersecretary at the State Department, was furious. In February 1951, he summoned a British official to Foggy Bottom and told him it was time for his government to make up its mind, regardless of what Anglo-Iranian Oil—later to be renamed British Petroleum—thought. “It was quite unjustifiable that the oil denial arrangements should not be completed to the last detail,” McGhee said, according to a British memo about the meeting. In response a few weeks later, the British offered a denial blueprint for Iran that depended entirely on military troops and suggested a similar approach for Iraq. According to British documents that reveal communication with the State Department, this proposal stunned U.S. officials, who believed the plan would fail without the expertise and manpower provided by the oil companies.

What the United States didn’t know, however, was that the British were in fact willing to tap their oil companies for assistance, and that the oil companies were willing to provide it. London just didn’t want the United States to be aware of this, for fear that U.S. knowledge would jeopardize the secret. “We are bound not to let them know how much British oil companies are cooperating,” said D.P. Reilly of Britain’s Foreign Office to a senior British military official, a few weeks after the McGhee meeting.

When George Prussing, the CIA operative assigned to work with Middle Eastern oil companies on denial plans, stepped into the State Department on May 1, 1951, he hoped to convince the two British diplomatic and military officials there to meet him that they needed the CIA’s help to salvage their strategies. He gave them for the first time a detailed briefing of the Aramco plan he had helped develop, hoping that it would serve as a model for the rest of the region.

The Aramco denial plan, according to British notes of Prussing’s briefing, was organized around the company’s three administrative districts in Saudi Arabia. Forty-five senior Aramco employees were “fully in the picture.” Altogether 645 employees were earmarked to participate, but most knew only of their individual roles to prevent disclosure of the overall plan.

In addition, five CIA undercover agents were embedded in Aramco in jobs such as storekeeper and general manager’s assistant. They were charged with keeping the intelligence agency informed of the company’s work on the denial plan and any developments that might affect it. Outside the CIA, only one Aramco executive and one State Department official were aware of the agents’ real jobs, according to the British notes.

The goal was to keep the Soviets from tapping Saudi Arabia’s oil and refined fuels for up to a year in the event of an invasion. The plan would unfold in phases, starting with the destruction of fuel stockpiles and disabling Aramco’s refinery. Selective demolitions would destroy key refinery components difficult for the Russians to replace. This would leave much of the refinery intact, making it easier for Aramco to resume production after the Soviets were ousted.

According to British notes of this meeting, the CIA had already imported military-grade explosives into Saudi Arabia, specially shaped to fit specific parts, to store in bunkers on Aramco property. Flame throwers were to be widely used to melt small equipment parts. Other weapons included special grenades tested for destroying fuel stockpiles. Cement trucks were ordered for plugging oil wells.

Trucks, railway cars, generators and drilling rigs were also slated for destruction. Aramco employees, besides receiving military commissions, would be evacuated to safety once the denial operation was completed, Prussing said.

The briefing impressed J.A. Beckett, petroleum attaché at the British Embassy in Washington, who fired off a telegram to London advising that Aramco and the CIA had “developed a satisfactory modus operandi for this type of covert planning and are most anxious to extend their activities to cover the remaining [oil] fields.”

Prussing sought approval to install Aramco-style plans in Bahrain, Kuwait and Qatar, where a mix of American and British oil companies were then operating, according to British documents. Britain, the governing authority in those countries, accepted Prussing’s proposal as long as Britain could remain responsible for triggering the execution of the denial plans in Kuwait and Qatar. (A decision about which country would order the plan to begin in Bahrain was deferred although Britain was inclined to give it to the United States.)

Britain remained responsible for developing the denial plans for Iran and Iraq, but Prussing offered the CIA’s assistance. To this end, British officials arranged a meeting in London for the next month, which is how Prussing ended up briefing executives from oil companies in Kuwait, Bahrain and Iraq in June 1951. There, according to British notes off of the meeting, Prussing reviewed the Aramco plan with the businessman and said he was ready to advise and assist their own denial plans. They agreed to the assistance.

Yet, there was one key oil empire conspicuously missing from the meeting: Iran. Arranging plans for that country was proving to be far more difficult than for the others.

In early 1951, Iran was a steaming stew of resentment toward Anglo-Iranian Oil. The British company’s shabby treatment of its Iranian employees and its mercenary grip on the country’s oil riches had long soured relations between the company and the country.

A group of Bedouin men working on the laying of a 560 mile long pipeline from Kirkuk in north Iraq to Bania on the Syrian coast for the Iraq Petroleum Company have lunch surrounded by sections of the pipe on March 4, 1952

Whispers about the denial plan were making things even worse. In December 1950, a Tehran newspaper published a story that reported rumors of high-level British government discussions to destroy Iran’s oil industry in the event of war—arousing astonishment and anxiety in Iranian political circles. The story also set off alarms bells in London and at Anglo-Iranian Oil, where efforts were redoubled to keep its cooperation a secret. Based on British Foreign Office documents detailing a conversation with an Anglo-Iranian executive, the company’s general manager was told—whether by his company or the government, it’s not clear—to disavow any knowledge of the denial plan. “The article was far too near the truth,” A.T. Chisholm, a company executive, said while dropping off a translated copy of the story at the British Foreign Office in London.

At the time, the British government owned 51 percent of Anglo-Iranian Oil, but an unusual clause in the ownership agreement prevented the government from being involved in the company’s commercial matters. According to Foreign Office documents discussing Anglo-Iranian’s participation in the plan, Fraser, the company’s chairman, shrewdly used this provision to push his view that the denial plan would be a financial disaster for the company. He warned that an American competitor might intentionally leak his company’s participation to Iran’s government to gain an advantage in the country—and he said he would not participate.

“He was convinced that no security measure would be effective once the American oil companies were brought into the picture,” said R. Kelf-Cohen, an official with Britain’s Ministry of Fuel and Power, during a meeting in London to discuss the denial policy.

But Fraser, under pressure after the McGhee meeting with British government officials in February 1951, eventually grudgingly agreed to allow a denial plan to use his company’s employees. He had conditions, though. His approval would be required, for instance, to execute the denial plan until he was sure the company could recover any financial losses incurred. The British government decided that his cooperation would be kept secret from the Americans so that U.S. oil companies didn’t try to undercut Ango-Iranian oil.

But then, Iranian politics put a wrench in the plan. On March 7, 1951, Iranian Prime Minister Ali Razmara was assassinated by a nationalist and was replaced in April by Mohammad Mosaddeq, who promptly nationalized the company.

>>

>> Seizure of Anglo-Iranian Oil’s assets by the Iranian government nixed the denial plan with consequences that threatened the entire NSC 26/2 policy. The company produced half the oil in the Middle East and more than half the gasoline, diesel and jet fuel. Its Abadan refinery was the largest in the world and by itself could probably satisfy a Soviet invasion’s thirst for fuel.

The nationalization triggered a scramble for options. According to British documents, the United States asked Britain if the plan’s mission to counter a Soviet invasion could be salvaged with airborne strikes aiding British troops on the ground. Britain rejected this idea, claiming spare troops were not available and the ground demolitions called for by the plan would be too dangerous without the expert assistance of refinery workers.

Iranian demonstrators are seen on the balconies of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’s information center in Tehran after they invaded the building, June 22, 1951.

According to British military documents, Britain’s Joint Chiefs of Staff, responsible for the country’s denial planning, decided instead that “oil denial [in Iran] can only be carried out by air attack.” Still, they were skeptical about having enough aircraft to successfully attack the massive Abadan refinery. Because of this fear, the plan that emerged was highly targeted: If the Soviets invaded Iran, the British Royal Air Force based in Iraq would attack fuel stockpiles at the Abadan facility, which was then idled by a British embargo of Iranian oil, leaving the refinery intact. British aircraft would snip production at the Abadan refinery, if reactivated, by bombing a railway that delivered crude oil to the facility. Airstrike’s would also hit two small refineries in Iran, at Kermanshah and Naft-I-Shah, along with their fuel stockpiles.

By late 1951, as the denial plan for Iran reorganized, the plan for Saudi Arabia was settling in. Prussing was even treating a handful of Aramco employees to a picnic in the desert where they discussed the gritty details of oil denial over sandwiches.

“Refinery explosions would work like Chinese firecrackers; when one exploded it would set off another,” Bill Otto, an Aramco employee and a manager of the company’s denial plan who was at the picnic, told me in an interview.

The CIA wanted a speedy timetable to ensure the plan could be completed before the Soviets arrived. The agency had already arranged a communications channel that would allow the U.S. secretary of state to send the order triggering the denial plan to a boat sitting off the shore of Saudi Arabia. Aramco did its part by filling binders with photos, diagrams and instructions needed to execute the plan. A handful of the company’s American employees stored the 20,000 pounds of dynamite and plastic explosives needed for the demolitions—a job done without arising suspicion since Aramco used explosives in its normal operations.

“The program didn’t have any meat to it until we started putting [demolition details] down,” said Otto, a former Army bomb disposal expert. “[The CIA was] happy to have someone else doing it.”

There were other signs of progress in the region, with Bahrain Petroleum Co. and Kuwait Oil wrapping up their Aramco-style denial plans while the British oil company in Qatar agreed to cooperate with the CIA, according to a National Security Council document tracking the denial plan’s progress. A U.S. delegation visiting the Middle East in late 1951 gushed that “pre-war plans for denial of oil facilities have never before been so perfected.”

But this confidence was premature as Aramco, Kuwait Oil and Bahrain Petroleum executives signaled second thoughts, according to a later NSC progress report. They told U.S. officials in 1952 that they had made no final decisions about their companies’ role in executing the denial plan. “I think they saw the difficulties,” said Parker Hart, the State Department consul general in Saudi Arabia at the time.

These difficulties included using employees to execute the policy. Though the companies had initially embraced the idea, they later had doubts about their authority to force workers to participate in the dangerous operation. That problem could be fixed by using volunteers, but the companies wanted military protection for them, something not part of the CIA’s plans. But the biggest issue for these companies, just like for Anglo-Iranian Oil, centered on the economic consequences if the denial plans leaked to the host governments: Aramco, for example, was producing more than twice the amount of oil it had been when it agreed to help the CIA in 1948—and bigger revenues meant the company was less prepared to risk Saudi Arabia’s wrath.

Looking for some insurance, Kuwait Oil and Bahrain Petroleum requested letters from the British and American governments stating their companies had been commandeered for the denial plan. They could show the letters to local government officials if the plan leaked, which they hoped would save their companies. But the State Department refused to provide the letters, saying they were unnecessary: There was ample evidence in its files to show it pressured the companies to cooperate. British officials summarily rejected the request, fearing the “demand for such a letter appeared to be a lever which might be used in any subsequent discussions on compensation.”

>>

>> The ruler of Kuwait sits with men from the oil company.

Aramco and Kuwait Oil, by then the largest oil producers in the Middle East after production plummeted in Iran following the nationalization of Anglo-Iranian, tried another route and pushed for disclosure of the denial plans to Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. The United States again refused, since it was about to ask some Middle Eastern countries to join a military alliance (which became the Baghdad Pact of 1955). U.S. officials believed disclosure of the denial policy could derail the fledgling alliance.

With that, Aramco decided the economic risk for the company was too great and demanded removal of denial plans and explosives from its property. The company believed the surge in denial training and the growing number of Saudi employees at Aramco made a security leak inevitable, and American diplomats in the country agreed. “You’d never get away with it,” said U.S. Consul General Hart to the State Department.

The setback in Saudi Arabia threatened to kill the denial policy as it limped into the Eisenhower administration in 1953. But just a few weeks after the new president’s inauguration, a report on NSC 26/2 landed at the National Security Council, and ignited efforts to save it. The author of the report was Walter Bedell Smith, a former chief of staff and trusted aide for Ike during World War II who was settling into a State Department job. He told colleagues he was “vexed” by the denial policy, and his report, seasoned by his recent three-year stint as CIA director, reflected it. He sketched out the plan’s problems, which went beyond Aramco’s reluctance to participate. The use of volunteers was under review, but they might not be as effective as hand-picked employees. The program to plug oil wells was also in trouble because of the time it took to complete the job. The report noted high-level discussions taking place about giving the U.S. military more responsibility for the denial policy, which would diminish the CIA’s control.

The report led with a bullet-point list of the changes in oil demand and supply since the approval of NSC 26/2 four years before. The United States had become a net importer of 600,000 barrels of oil per day, double what it was in 1949, and the United Kingdom’s demand for imported oil climbed had to 161 million barrels in 1952, up from 126 million barrels just three years earlier. During the same period, Middle East oil production had soared to meet the needs of the West.

A follow-up review found that while denial plans were still needed to counter the Soviets, it was increasingly important that Middle East oil be preserved for later use by the West. The denial policy’s use of selective demolitions promised a quick production rebound once the Soviets were ousted. The problem was with plugging the oil wells, which could take a week or more to do—not fast enough in the face of a rapid Soviet assault. Unplugged wells could allow the Soviets to cause permanent damage to the oil fields, by setting the wells on fire or letting them flow freely.

A fisherman throws a net in the Persian Gulf. Behind him in the distance stands a large refinery of the Bahrain Petroleum Company, in 1955

>>

>> In 1954, Eisenhower approved NSC 5401, which straddled these disparate goals. The new policy called for “conservation” of Middle East oil, with more emphasis on plugging oil wells in a timely way, while also maintaining ground demolitions. At the same time, a last resort plan was added: If the companies were unable to execute ground demolitions, the U.S. military would destroy the oil facilities with airstrikes.

The State Department also eyed the military to fill the vacuum left by Aramco’s refusal to execute the ground demolitions—that meant sending in troops to do the job. But the Defense Department pushed back. Smith told the National Security Council, as it mulled approval of NSC 5401, that he understood the military’s reluctance but it was inevitable that oil denial in Saudi Arabia was primarily a military job. Allen Dulles, by then director of CIA, agreed that for Saudi Arabia if “anything at all were to be done on D-Day, it would be done by the military.”

But the Defense Department, anticipating a shortage of troops in the region, refused to commit to ground demolitions. Airstrikes were still available as a last resort, but they were not ideal since disabling rather than destroying the fields was the preferred outcome. “The most therefore that could be hoped for was the [ground demolition] job could be done by experts from Aramco and the CIA with some degree of protection by the military,” said Robert Cutler, Eisenhower’s special assistant for national security, according to a National Security Council document in December 1953.

Had Aramco changed its mind? Cutler left it an open question, but William Chandler, vice president at the time of Aramco-owned Tapline, said in an interview before his death in 2009 that the company did resume cooperation, at least to some extent. He received a call in early 1954 from an Aramco executive to expect a briefing about a “special program” involving Tapline, which operated an oil pipeline across Saudi Arabia. The plan was to disable the pipeline if the Soviets invaded by destroying key valves in its pumps. Company supervisors were trained to use plastic explosives, which they stored in footlockers under their beds. “It was something we were ordered to do,” said Chandler.

Meanwhile, Britain was also rethinking its denial plans for Iran and Iraq. In 1953, a coup in Iran, backed by the United States and Britain, installed a friendlier government. An oil consortium, majority owned by British Petroleum and the four American oil companies that owned Aramco, was created to manage the bulk of the country’s oil industry. But Iranian government owned facilities were emerging despite the consortium, according to British documents.

The same thing was happening in Iraq, where hundreds of Iraq Petroleum employees were prepared to disable the company’s massive Kirkuk petroleum complex. The British company’s grip on the Iraqi oil industry had loosened, and the country’s government controlled refineries in Baghdad, Basra and Alwand.

For the denial plans to succeed in these countries, these government-controlled facilities had to be sidelined as well as all the others. But asking Iran and Iraq’s governments to develop denial plans would confirm existence of the policy and likely cause the two countries to lose confidence in their Western allies. That left Britain with the option to use airstrikes, but the military was wary of that option: German refineries during World War II had proven difficult to knock out using conventional bombs.

In 1955, when Britain was just starting to stockpile nuclear weapons, Britain’s Joint Chiefs of Staff showed interest in using nuclear weapons to destroy oil facilities in Iran and Iraq. The “most complete method of destroying oil installations would be by nuclear bombardment,” read a 1955 report endorsed by Britain’s Joint Chiefs of Staff. It’s not clear if U.S. officials were involved in these discussions at this stage. But according to British military documents, reviewing denial plan options, the Joint Chiefs, had minister-level approval to ask the United States to help by using some of its nuclear arsenal on Iran if the denial plan were triggered, according to British Ministry of Defence documents. The request was discussed in a meeting with U.S. officials in London in early 1956. Meeting records don’t mention any American reaction to the proposal. But a decision was deferred until Prussing could review the denial plan for Iran and inspect its oil fields and facilities. A British memorandum to Britain’s Joint Chiefs of Staff after the meeting said in the “near future, the only feasible means [in Iran] of oil denial would be American nuclear action.”

After returning from Iran, Prussing concluded that oil denial using ground demolitions was still workable for the country. In British military documents dated after Prussing’s review, British officials noted the growing number of U.S. nationals working in Iran made it increasingly likely that ground demolitions would be successful, and that nuclear destruction wouldn’t be necessary. Otto, Aramco’s expert on ground demolitions, was dispatched to help the British restructure its denial plan for Iran.

Elsewhere, Britain and the United States agreed to extend the reach of the denial policy. A refinery in Lebanon owned by predecessor companies of Chevron and Texaco, and a British refinery in Egypt for the first time were covered by denial plans. A proposed refinery in Syria was slated for one as soon as it was completed. The United States agreed to be responsible for denial planning in the Kuwait Neutral Zone, a patch of land between Saudi Arabia and Kuwait. The British identified refineries and pipelines in Israel and Turkey to eventually target.

The progress was encouraging enough for the State and Defense Departments and the CIA in 1956 to propose continuing the denial policy essentially unchanged. But a junior staffer at the National Security Council had a different idea. He believed changing politics in the Middle East meant that “the whole operation” should be killed.

George Weber, 31, was no stranger to the denial policy, having assisted the government committee whose recommendations led to NSC 5401. But by 1956 the University of Cincinnati graduate and NSC staffer believed it should be shelved, in part because it only dealt with a war involving the Soviet Union. By that year, the Soviets weren’t the only problem for Western nations in the Middle East; burgeoning Arab nationalism movements were also a threat to the West’s hold on regional oil. President Gamal Abdul Nasser’s 1956 nationalization of the Suez Canal was a prime example.

Weber also questioned the usefulness of selective demolitions to disable facilities since the Soviets would probably completely destroy them when forced to retreat. Meanwhile, increased selective-demolitions training by the oil companies was raising chances of a security leak, “I think the Council should review very carefully the wisdom of such a program,” he said in a memorandum to Cutler, Eisenhower’s national security adviser.

The denial policy was not killed, but Weber triggered a transformation, and in a few months Eisenhower approved its replacement: NSC 5714. The destruction of oil facilities in the event of a Soviet invasion remained part of the plan as a last resort, but only with “direct military action” as opposed to employee involvement directed by the CIA. The CIA partnership with the oil companies was abandoned. “Covert denial by civilian agencies had become impracticable,” said William Rountree, a State Department official, in a memo.

>>

>>

>>

>>

>>

>> The new policy also became more preemptive, swinging toward protection of oil facilities in the face of new threats in addition to Soviet invasion, like sabotage and regional war. In this, Middle Eastern countries were to be asked to play an unprecedented role. Oil companies and local governments were to work together to boost security, including hardening oil facilities for protection against attack. Local governments would also be asked to cooperate in plugging oil wells if they were threatened to save the oil for later use by the West.

“Thus the evolution of this policy has taken another step,” Weber said.

The shift did not put an end to other American and British plans involving Middle East oil. A broader U.S initiative in 1958—unrelated to NSC 5714—called for the possible use of military force as a last resort against Arab nationalists, to keep the oil flowing at reasonable prices. The British in 1957, deeming a Soviet invasion unlikely, refined plans to use its military to protect oil installations in Kuwait, Bahrain and Qatar if threatened by “Egyptian subversion.”

>> On the left, an aerial view of a town erected by Aramco to house some 1500 American oil workers and their families in Saudi Arabia, 1947. On the right, an Aramco drilling rig at Rub’ al Khali in the Arabian Peninsula, circa 1955

How NSC 5714 fit in to this new Middle Eastern security landscape is unclear. It was put in place, but the handful of declassified documents reveals little about its fate, including whether or not any local governments agreed to cooperate. In 1963, the Kennedy White House asked the State Department whether NSC 5714 should be rescinded, replaced by something else, or if it still represented U.S. policy. That is the last document I was able to find about the denial plan in America or Britain. A response is not in the file, and it’s unclear when the policy ended.

Those in the field did notice the shift brought on by NSC 5714. Otto was instructed to destroy the 10 tons of explosives stashed at Aramco, which rattled windows miles away. He was also was dispatched in the late 1950s to Tapline to remove the explosives still tucked under the beds of supervisors. Chandler, who became president of Tapline, was relieved to see them gone. The Saudis believed they owned the pipeline and would have been furious about the denial plan.

So why take the risk from the start? Patriotism was high in the years after World War II, Chandler later recalled, and so was the willingness to help the United States in its fight against communism.

“We had a good crowd and we didn’t have complaints and that was the amazing thing,” he said. “It was just we had to do this and everyone went along with it.”

Steven Everly is a former reporter for the Kansas City Star. The National Security Archive, a non-governmental institute based at George Washington University, is posting U.S. and British documents about the denial policy. They are available by clicking on the following link:

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community