Most of the sanctions on Iran were lifted earlier this year, but the expected rush of international investment has yet to follow. Instead, things have been going frustratingly slowly when it comes to deals being signed.

Trade delegations from Europe and Asia have been filling hotel rooms in Tehran, keen to find out more about a country of 80 million consumers and a well-diversified economy that is the 18thlargest in the world. But not too many of these missions have led to contracts being signed or investments being made.

There are a few good reasons for the impasse, both inside Iran and outside the country. Here are the biggest problems holding things back:

1. The lack of banking links

This is the big one. International companies wanting to do business in and with Iran need to be able to move money in and out of the country and for that they need banks. Iranian banks have been allowed to rejoin the international bank messaging system, Swift. But there are other obstacles still in place which make moving money across the frontier difficult if not impossible.

The problem has its roots in the sanctions era. When large international banks were caught evading sanctions in the past they struck deferred prosecution agreements with the US authorities. These are understood to include conditions whereby the banks promise not to re-engage with Iran for a number of years. If they do they could face huge fines and even, in extremis, the loss of their US operating license. As a result they dare not try to take advantage of the new post-sanctions opportunities. Lord Lamont, the UK trade

2. Some sanctions are still in place

The nuclear sanctions that were removed in January were only one element in a dense network of embargoes and trade restrictions on Iran. There are still several other groups of sanctions in place, designed to punish the country for human rights abuses and terrorist financing. Some nuclear-related sanctions are also still in force and will remain so for several more years. Several hundred Iranian individuals and companies are caught up in these measure. International companies are extremely wary of inadvertently doing business with them.

The most problematic measures are the ongoing US sanctions. The Iranian market is off limits to most American citizens and companies, including US banks, with only a few exceptions. For the rest of the world this means they can’t do any deal with Iran involving US dollars and if a company has US employees it has to ensure they have no involvement in any Iranian transaction.

envoy to Iran, says British banks are “terrified” of being caught doing anything with Iran.

3. The Revolutionary Guards

The Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corp (IRGC) is a military organisation but also a heavyweight in the Iranian economy and its tentacles reach into almost every sector, from telecoms to transport to engineering and construction. It is also still firmly under international sanctions. Over the years it has become adept at disguising its involvement in companies.

That makes it extremely difficult for an international company to be sure that it is not doing business with the IRGC. Even very thorough due diligence may not uncover IRGC involvement and that makes international businesses understandably nervous. “When I talk to clients and potential investors this is one of the biggest concerns,” says Matt Townsend, a partner at law firm Allen & Overy.

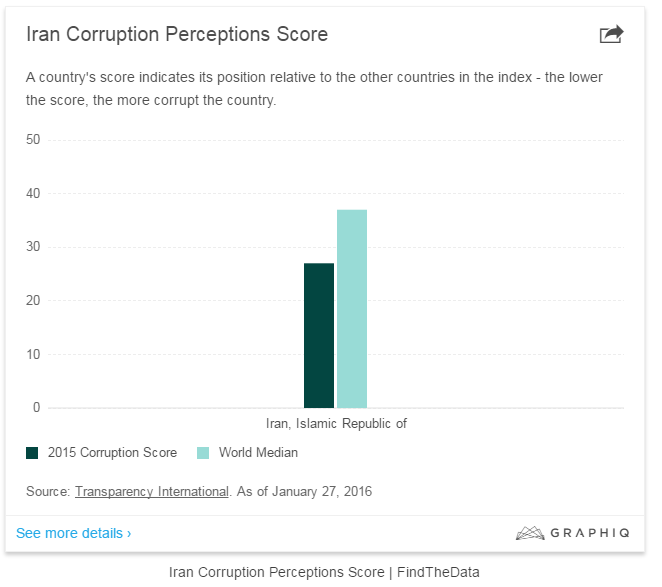

4. Corruption

Iran does not fare very well in many international league tables and corruption is no exception. Iran is ranked at 130 out of 167 countries in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index. The government in Tehran has vowed to tackle the problem, but it’s not likely to disappear any time soon.

“Corruption is absolutely a problem,” says Charles Robertson, global chief economist of Renaissance Capital. “Corruption is going to remain a problem in Iran for the next five to ten years.”

5. The next president of Iran (and the US)

Presidential elections are on the horizon in both the US and Iran, which adds another element of political risk for companies thinking of investing.

Forecasting political events in Iran is a fool’s errand, but at this stage President Hassan Rouhani looks well placed to win a second term next year. That should ensure continuity in Tehran, but the situation in Washington also raises questions for investors.

Most of the Republican candidates for president have vowed to tear up the nuclear deal with Iran. The one exception is, perhaps surprisingly, Donald Trump who has said he will enforce it rigorously. It will not be easy for any US president to annul the deal given the international support it has, but company bosses may still decide it’s best to delay any major investment in Iran until they have a better idea of who will be the next resident of the White House.

6. Currency risk

Iran is one of those countries that have not one but two exchange rates: an official one and a market one. The difference between the two has narrowed substantially over the past year but it remains significant, with the official rate at around 30,000 rials to the US dollar compared to the open market rate of around 37,000 rial.

If you’re sending money through official banking channels you have to use the official rate, which equates to an extra cost of more than 20%. The government has vowed to eliminate the exchange rate gap as soon as it can. Until it does, some companies might prefer to hold off making any formal investment.

7. Snapback

A big fear among some companies is that the whole nuclear deal could come crashing down if Iran fails to meet its obligations under the accord. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action signed by Tehran and the six international powers last year includes a provision for ‘snapback’, a process under which the sanctions that have been lifted would be re-imposed if Tehran was found to have flouted the terms of the deal.

Most observers say it is highly unlikely that would happen, but it is still a risk that needs to be weighed up. “Everyone tells us snapback is only a hypothetical thing, but then why did they put it in the deal?”asks Andreas Schweitzer, senior managing partner at Arjan Capital.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community