Anger at spending on Islamic institutions as soaring living costs hit poor

Najmeh Bozorgmehr in Tehran 17 January 2018

When President Hassan Rouhani unveiled this year’s budget his intention was to shine a spotlight on state funding for institutions under the influence of his hardline opponents. Instead, his attempt at transparency inadvertently stoked public anger that helped trigger the biggest anti-regime protests in almost a decade.

As disgruntlement festered over rising living costs and complaints that Mr Rouhani had failed to back his promises of reform grew louder, the budget exposed the large amounts of taxpayers’ cash allocated to religious institutions and other entities affiliated to factions within the Islamic regime.

One example picked up on by Iranians was the 31.1trn rials ($853m) proposed for about a dozen institutions that promote Islam and the ideological foundations of the Islamic regime. This was a nominal increase of 9 per cent on the previous year and almost the equivalent to the amounts earmarked for the foreign and culture ministries.

At the same time, the December budget, which has to be approved by parliament by March, proposed increasing fuel prices by as much as 50 per cent and amending the welfare system in a move that could end monthly state payments for more than 30m people.

Iranians typically ignore what is a complicated budget process in an opaque financial system. But this time they paid attention as Iranians used social media to post extracts of the government’s spending plans to expose perceived injustices. And it lit a fuse after years of pent up frustration with a theocratic regime among a young, urbanised population fed up with corruption, high unemployment and social restrictions.

“We have to shed tears for ourselves, our families and our country when the budget for the Food and Drug Administration [2trn rials] is less than the budget for the insurance of seminary scholars and unemployed clerics [2.9trn rials],” read one post on Telegram, the messaging app.

The fact that the government of Mr Rouhani has increased spending to religious entities that traditionally relied on donations and agencies under the sway of regime hardliners, exacerbated Iranians’ disillusionment with their leaders. A pragmatic politician, he secured a second term with a landslide election victory in May on a reformist agenda that raised the expectations of Iranians desperate for change.

“Where has that money gone?” asked Saeed Laylaz, a reform-minded economist, citing the hundreds of billions of dollars in oil revenue the Islamic republic has received since 2005. “There are 35m people under the poverty line and 3.2m people who sleep hungry every night.”

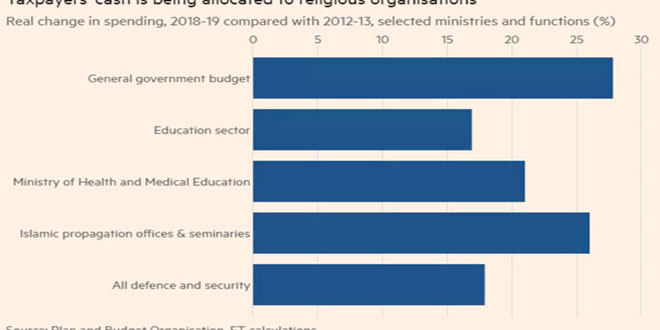

Research by the Financial Times reveals that since Mr Rouhani replaced Mahmoud Ahmadi-Nejad, a hardline president, in 2013, the budgeted spending on defence and security has increased 18 per cent in real terms and allocations for Islamic propagation offices and seminaries have risen by 26 per cent. Over the same period, spending for education and health increased by 17 per cent and 21 per cent in real terms respectively, while the culture ministry’s budget fell by 12 per cent.

About a fifth of the December budget, or $22.1bn, has been earmarked for defence, — almost equivalent to the combined allocations for education, health and social welfare. Of that, $7.7bn is allocated to the Revolutionary Guards, a powerful hardline force that also runs a huge economic empire.

The guards’ overseas arm, the Quds force, is active in conflicts in Syria, where Tehran is believed to have spent billions of dollars propping up Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, and in Iraq where it has been active in the fight against Isis.

When thousands of protesters took to the streets of towns and cities across the country this month, many chanted “Give up on Syria, think of us!”. The protesters also chanted “Death to Rouhani,” and in some towns attacked state buildings, including police stations and banks. At least 25 people, including a policeman and a guards officer, were killed in the 10 days of unrest.

The budget does not refer to the Quds forces. There are, however, about a dozen projects named after martyred commanders and ideological causes that will receive $1.7bn of the guards’ funding this year.

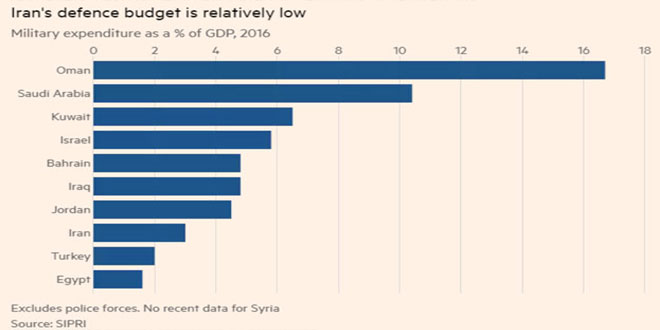

Tehran argues that its defence budget, about 5 per cent of gross domestic product, is not unduly high given the fact that it shares porous borders with countries blighted by conflict. And it is far less than the $84bn (about 10 per cent of GDP) Saudi Arabia, Iran’s main regional rival, plans to spend on defence in 2018.

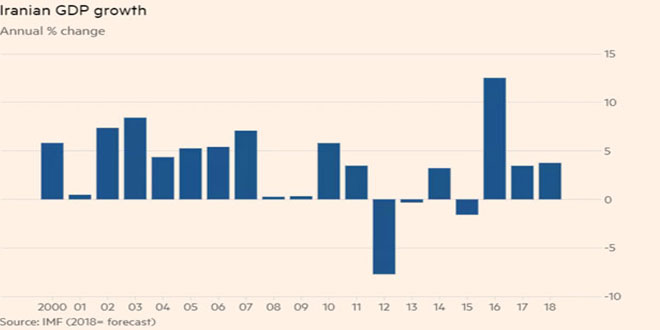

But the furore over the state’s spending plans underlines the challenges Mr Rouhani faces as he struggles to make state entities affiliated to hardliners more accountable and revive an economy that was battered by years of sanctions and populist policies during Mr Ahmadi-Nejad’s two terms.

Annual inflation has fallen from over 40 per cent when Mr Rouhani took office in mid-2013 to 10 per cent, but Iranians’ living costs have risen almost 60 per cent during that time.

Reformist politicians allege that hardliners tapped into people’s frustrations to orchestrate the December 28 rally in Mashhad, which was the catalyst for the nationwide protests, in an attempt to undermine the president and his reforms.

“Mr Rouhani is unable to make the budget transparent. His first step to make hardliners more accountable was answered by the unrest,” said a former finance official. “About 20 or 30 per cent of the budget is spent on [promoting] the Islamic regime’s ideology in various forms and satisfying loyal forces. How can that become transparent?”

Oil exports have more than doubled since Mr Rouhani sealed the 2015 nuclear deal with world powers, helping drag the economy out of recession, and his government has overseen a rise in tax collections. But powerful religious bodies and “revolutionary” institutions of the Islamic regime, are only expected to pay $11.2m of $35bn in tax revenue targeted for this financial year.

The president, who has vowed to crack down on corruption and sought to curb the guards’ business empire, has hinted that he wants to use this month’s unrest to press his case for reforms and greater transparency. But many of the 24m people who voted for him are still not convinced he will deliver.

“Rouhani failed us. I feel hurt by seeing clerics get their budget as usual but the poor will get poorer by day,” says Maryam, a 32-year-old housewife. “Protesters are right. There is no more hope in any reforms. They [Iranian leaders] are all the same.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community