THE WASHINGTON POST

By Adam Bernstein

Richard H. Solomon, a China scholar who assisted in the historic “Ping-Pong diplomacy” that led to the opening of U.S.-Sino relations in the 1970s, who became an authority on China’s pressure tactics during negotiations and who, as a top American diplomat, helped end a long-running conflict in Cambodia, died March 13 at his home in Bethesda, Md. He was 79.

The cause was brain cancer, said his wife, Anne Solomon. He retired in 2012 after 19 years leading the United States Institute of Peace, a congressionally funded research group for conflict resolution.

Dr. Solomon was an intellectual polymath whose interests encompassed science, photography and international affairs. His career took him from academia to senior positions in government and think tanks.

He joined the Institute of Peace after seven years with the State Department, where as assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs from 1989 to 1992 he represented the United States in peace talks on Cambodia. He also served six months as ambassador to the Philippines.

His State Department portfolio, at various times, included democratization movements from Manila to Santiago, Chile, and nuclear arms talks with Moscow and Pyongyang, North Korea. Secretary of State George Shultz praised Dr. Solomon’s skill in strategic long-term planning, particularly on the “evolving relationship” with the collapsing Soviet Union.

But the central focus of his life’s work was China.

In his books — perceptive volumes on revolutionary leader Mao Zedong and Chinese political negotiating strategies — he sought to help U.S. policymakers comprehend a land that for decades was an almost hermetically closed society, hostile toward the West and little understood outside its borders.

Dr. Solomon’s mentor had been Lucian Pye, a noted political scientist and China watcher who helped broaden the parameters of his field to include psychoanalytical and cultural explanations when interpreting behavioral patterns and styles of leaders. Dr. Solomon followed in Pye’s tradition with books such as “Mao’s Revolution and the Chinese Political Culture” (1971) and “A Revolution Is Not a Dinner Party” (1976).

Roderick MacFarquhar, a China scholar at Harvard University, said the books revealed Mao as a man who, as a matter of character, “loved upheaval and revolutionary upsurge.” He said Dr. Solomon provided “very important insight” into how Mao shaped China’s communist system to mirror his own tumultuous personality.

Orville Schell, an author and China authority who is now director of the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations, said Dr. Solomon’s books “help explain the depth of the animus that Mao felt about not only authority figures within China, but how he projected that onto the great powers he saw as oppressing and exploiting China.”

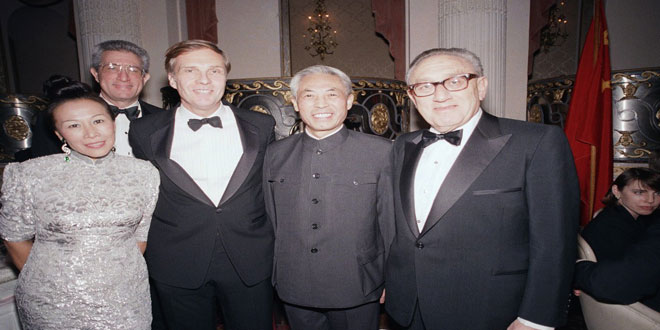

Dr. Solomon had an extraordinary opportunity to help shape China policy when, in the fall of 1971, he was hired by the National Security Council. Virtually no Americans had been on the Chinese mainland since the communist revolution in 1949. But several diplomatic overtures by the Nixon administration, spearheaded by then-national security adviser Henry Kissinger, helped set in motion a thaw in U.S.-China relations.

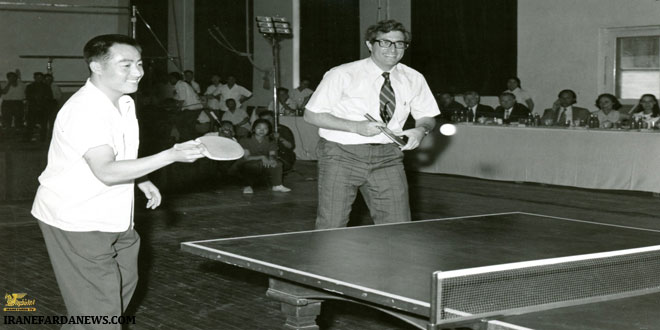

The U.S. table tennis team made a momentous visit to China in April 1971, and President Richard Nixon and Kissinger traveled to Beijing the following February. One of Dr. Solomon’s responsibilities was to escort the visiting Chinese table tennis team around the United States in April 1972 — a trip seen as an important step in reciprocal trust-building.

Dr. Solomon continued to organize cultural and academic exchanges with the Chinese until leaving the council in 1976 to lead the political science department at the Rand Corp. think tank.

One of his most consequential works at Rand was a study commissioned by U.S. intelligence agencies on Chinese political negotiating behavior. In many instances, Dr. Solomon drew directly from his close-up dealings under Kissinger and with the Chinese.

The study, published years later for a general audience, assessed what Dr. Solomon called “a range of manipulative strategies, enticement tactics and pressure tactics” that anyone negotiating a business contract or treaty with the Chinese government would need to understand.

James Mann, a journalist and author who has written extensively about China, called it “a landmark study and a brilliant one” that laid out a “series of cautions” about how China managed frequently to come out ahead in diplomacy. Among the concepts were negotiating on one’s own turf, creating a sense of grandeur and managing personal relationships with opponents in ways to serve Chinese interests, such as exploiting their rivalries and insecurities.

Dr. Solomon noted that the Chinese were deft at enticing the other side to make an opening bid in bargaining — even when they were the guests of a host country.

“We have two sayings,” he quoted Foreign Minister Qiao Guanhua telling Kissinger at one meeting in New York in 1976. “One is that when we are the host, we should let the guests begin. And the other is that when we are guests, we should defer to the host.”

Kissinger laughed off the quip, then proceeded to volunteer: “I will be glad to start.”

Richard Harvey Solomon was born in Philadelphia on June 19, 1937. He was 8 when his father died of a pulmonary embolism and his mother took over his job as a furniture salesman. He was from a Jewish family but attended a nearby Quaker boarding school, where he excelled in the sciences.

He majored in chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology but, on a campus teeming with academics who doubled as high-level scientific advisers to the government amid the Cold War, he found his interests drifting toward international affairs.

He received a bachelor’s degree in 1960 and a doctorate in political science in 1966. He spent five years teaching at the University of Michigan before going to the NSC.

His first marriage, to Carol Schwartz, ended in divorce. Survivors include his wife of 25 years, Anne Greene Keatley Solomon of Bethesda; two children from his first marriage, Lisa Solomon of Santa Monica, Calif., and author and Wall Street Journal reporter Jonathan “Jay” Solomon of Washington; a stepson, Eric Keatley of Manhattan; a brother; and five grandchildren.

Shultz recruited Dr. Solomon to the State Department in 1986 to lead the policy planning staff. He was named assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs just as U.S. relations with China plummeted after the Tiananmen Square massacre.

With little appetite in Washington for normal relations with China, he directed his attention to the bloody conflict in Cambodia. The country had endured the barbarity of the Khmer Rouge regime in the 1970s, followed by Vietnamese occupation and seemingly intractable fighting between warring factions.

Dr. Solomon urged Secretary of State James Baker III to make a push for a settlement brokered by the United Nations Security Council’s five permanent members. The time was ideal, Dr. Solomon said, because the collapse of the Soviet Union meant a cutoff of Soviet aid to the Vietnamese.

Nayan Chanda, a journalist and author of “Brother Enemy,” a well-regarded account of the Cambodian-Vietnamese war, called Dr. Solomon “one of the key architects of the Cambodia peace accord,” noting in particular his assessment about the Soviets and his “indefatigable efforts during the protracted peace negotiations” that led to a peacekeeping mission and U.N.-monitored elections in 1993.

That year, Dr. Solomon took over the Institute of Peace and oversaw the completion of its $180 million steel-and-glass headquarters at the corner of Constitution Avenue and 23rd Street NW, facing the Lincoln Memorial.

In 2005, he received an American Political Science Association award for notable public service.

In a 1996 oral history interview with the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Dr. Solomon recalled that his trips to China were invaluable lessons in diplomacy — not only with the Chinese but also where his boss, Kissinger, was concerned.

At one gathering, Dr. Solomon said he had accepted the congratulations of Premier Zhou Enlai on his ability to speak Chinese when “Kissinger’s head snapped around” and made clear his displeasure at being upstaged.

The next day, Dr. Solomon said, then-Vice Foreign Minister Qiao, “a rather provocative character, turned to me and said something in Chinese that should have called for a response in Chinese, which I did not do. In any event, that was a very interesting personal experience being in China for the first time, and with Kissinger.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community