By JENNIFER HUNTERThe Reader

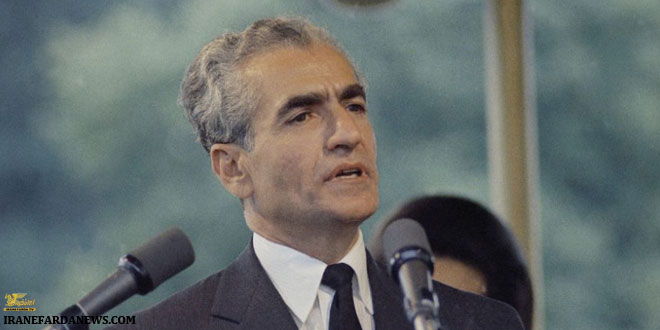

In his book The Fall of Heaven, author Andrew Scott Cooper attempts to “humanize” Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the shah who was swept aside by the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

The shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, went into exile in 1979 following a ruthless revolution that tilted the country from a largely westernized culture to an Islamic regime, ruled by ultra-conservative ayatollahs. At the time, author Andrew Scott Cooper was 9 years old but he followed the events on television and became gripped by what was unfolding. Later, Cooper did graduate work in the history of Iran and wrote two books about the country. The most recent, The Fall of Heaven: The Pahlavis and the Final Days of Imperial Iran, is based not only on documentary evidence but also on interviews with the shah’s widow, Queen Farah, former U.S. National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and other witnesses who watched the unravelling of the Persian kingdom. Our conversation has been edited for length.

Jennifer: I want to ask about your research. You spent over a year constructing a 242-page timeline from January 1977 to Aug. 1, 1978. Yikes!

Andrew: It allows me to keep control of thousands of pages of documents. I had classified U.S. government documents, translated accounts and newspaper articles from the 1970s. The only way I could keep track was to create a timeline.

Jennifer: You write with great empathy about the shah, but he was indecisive, out of touch with his people and took counsel from advisers who were never going to tell him the truth.

Andrew: I wanted to humanize the shah. The most traditional narrative is that he was a bloodthirsty autocrat who suppressed human rights. I try to present the shah as a fully rounded human being who had character flaws but was trying to do what he thought was the right thing.

Jennifer: Look how he treated his wife. He had a Parisian madam flying prostitutes to Tehran whom he would meet in a safe house. And Farah knew.

Andrew: It was the 1970s. There wasn’t social media and the Internet and people could get away with this stuff. So many people in Iran, middle-class people, knew about the shah’s womanizing. It wasn’t a state secret.

The other leader I would draw parallels to is John F. Kennedy, who also ran enormous personal risks. There is something about power and male authority figures who think they can get away with it. Look at Bill Cosby.

Jennifer: Was the revolution in Iran merely a reflection of the student uprisings in the U.S., France and elsewhere? Was it just a time of protest?

Andrew: I thought about that a great deal as I was writing the book. The revolution in Iran was of a time and place. Youth unrest in Europe and the U.S. started in the mid-1960s and continued into the 1970s. In Iran there was a generation coming of age. Many of these people had been educated in the U.S. and Europe. They went back to Iran and took the tools of protest with them.

Jennifer: Ayatollah Khomeini, the religious leader prominent in the overthrow of the shah, was tutored by advisers when he was in exile to hide his misogyny and his extreme political views. In fact, he came across as being very avuncular and hid his views so well that people thought of him as another Che Guevara.

Andrew: People say the shah was dictatorial, but the dictatorial one was really Khomeini. His advisers told him to tone it down when it was apparent he was going to inherit power because he was scaring people. A lot of Iranians say, “We were lied to.” I don’t buy that. If you read his thesis from 1970, which was widely available, you get a sense that this guy was a theocrat and not afraid to use violence in pursuit of power.

Jennifer: But he was very convincing.

Andrew: The U.S. ambassador compared him to Gandhi. Even the American ambassador saw this guy as an elderly peace-loving statesman who had come back to Iran to serve as a figurehead. The Americans did not understand Iran at all.

Jennifer: North Americans, you write, think of the shah as perpetuating repression and allowing mass murder. You say this is misguided and point to his achievements.

Andrew: Enough time has passed since the shah fell for us to have a clearer view of what was going on inside Iran. When I travelled there, I was surprised at the infrastructure of the country. The shah left behind solid, tangible evidence of his accomplishments: health care, literacy and education.

The shah’s attempts to modernize and westernize Iran appeared to collapse in total failure in 1979 but many of the programs he put in place continue today. They’ve just been given new names. Khomeini inherited a country with a very effective central government. He inherited a country that was well on its way in science and technology.

Jennifer: Under Khomeini, women lost their rights. Human rights began to disappear. People didn’t realize at first that this would happen.

Andrew: Many of the young women who opposed the shah and came out in support of Khomeini were university-educated. When Khomeini came back, women took on the chador. They saw it as a political statement. Then they realized they would never be able to take it off again.

The story of the Iranian revolution is disturbing on many levels. We have to keep learning and reading to try to draw out the real story.

I am passionate about getting people to read history. More awareness in our society would help us understand things today and make decisions in the future.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community