the guardian-

Rules impeding the progress of female politicians in the Islamic republic remain firmly in place and the battle to change them advances slowly

By: Farnoosh Amirshahi

Traditionalist clerics often invoke a masculine term to discourage women from running for political office in Iran. While the question of gender isn’t addressed in Iran’s electoral laws, candidates wishing to participate in the Iranian political scene must be considered “Rajol-e-siasi,” or statesmen. If the political arena is legally defined as the purview of statesmen, women have no business entering it, conservatives argue.

This paradox helps explain the status of female politicians in a system where only 49 women have served in parliament since 1979, accounting for only 3% of all parliamentary seats. To maintain any presence at all, female lawmakers must reconcile conservative Islamic values with the social advancement of their gender.

Even if they possess an immaculate political and theological pedigree, female politicians struggle to advance their agendas without altering traditional women’s roles as defined by male Islamic jurists. When addressing basic issues such as workforce participation, successful female lawmakers like conservative MP Soheila Jelodarzadeh take care to only support part-time employment, prioritizing women’s roles as mothers and homemaker.

Outspoken female parliamentarians from across Iran’s political spectrum have been ostracized, even jailed, for their overly progressive views. Others have maintained a merely ornamental presence in politics, voting along factional lines and against their own interests as women.

Iranian women attend a campaign for the upcoming parliamentary elections at the Hejab Hall in downtown Tehran on 18 February.

“Most of the women MPs of the current parliament have not only failed to achieve anything remarkable in the field of women’s rights, but supported anti-women ideas, remained silent and approved such ideas,” Fatemeh Rakei, a reformist political activist, told Isna news agency last April, criticizing female MPs’ silence on such topics as gender segregation at universities, women’s presence at sports complexes, and bills supporting polygamy and temporary marriages.

President Hassan Rouhani has often advocated a greater role for women in the Islamic republic’s public sphere, most recently in an 8 February speech at a conference titled “Women, Moderation and Development.”

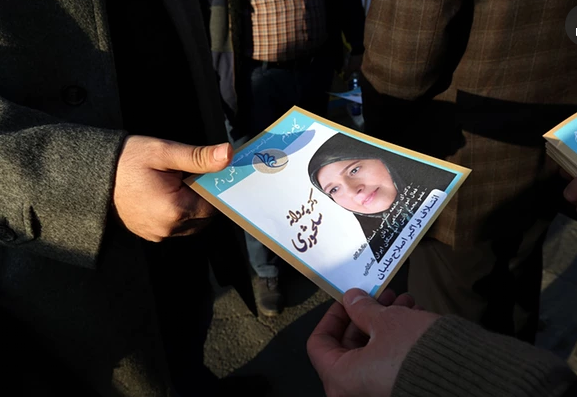

An Iranian man hands out leaflets for reformist candidate Parvaneh Salahshori in the upcoming parliamentary elections.

Encouraged by the promises Rouhani made during his presidential campaign, Iranian women’s rights advocates viewed the upcoming 26 February election as an opportunity to increase their presence in parliament and break into the all-men’s club of the Assembly of Experts, a body charged with choosing Iran’s next supreme leader.

“Towards changing the masculine face of parliament,” a campaign launched last October, aims to raise the number of seats held by female members of parliament from the current 9% to 30%.

But as in the 8 February speech, in which Rouhani said “Women have a big responsibility on their shoulders” and “must fulfill a significant and influential presence” in all fields, the government has done little to show female politicians how they might achieve these goals.

Of the 12,000 candidates for the parliamentary election, more than 1,400 were women. The Guardian Council has qualified 584 of them. Of the 801 total candidates for the Assembly of Experts, all 16 women were disqualified.

Iranian women wave flags of reformists for the parliamentary elections in a campaign rally in Tehran.

To date, only one woman, Zohreh Sefati, a Mujtahid who co-founded the women’s branch of the Qom seminary, passed the stringent vetting of the Guardian Council in 1998. Despite her exemplary credentials, she withdrew her candidacy after a conservative cleric opposed the presence of women in the Assembly.

Despite Rouhani’s campaign promises to eliminate gender discrimination, the current government hasn’t followed up on plans to establish a ministry for women’s affairs. Within the cabinet, all ministerial positions have been filled by men, while women hold subordinate roles as deputies or the heads of governors’ offices.

Last year, Shahindokht Molaverdi, vice president for women and family affairs, asked the Expediency Council to modify the election rules in favor of women, including measures to gradually increase their representation in parliament and city and village councils. The suggestion didn’t gain enough votes at the Expediency Council.

Iranian women, among them activists in the foreground, attend a reformists campaign rally for the parliamentary elections in Tehran.

Women’s rights activists say the key to securing a broader space in the Iranian political sphere is to nurture a dialogue that bridges deep-seated factional divides. Non-collaboration could lead to such disasters as the 2007 debate overMahmoud Ahmadinejad government’s family support bill, whose original wording freed men from the obligation of registering temporary marriages and obtaining their first wife’s consent if they wished to marry a second one.

While reformist female MPs called the bill “catastrophic,” women from conservative factions went along with the opinions of their male colleagues. Laleh Eftekhari, a principlist MP, and speaker of the women’s faction of parliament, advised lawmakers not to abide by what the international community says, adding that “Based on God’s order and Sharia, a man doesn’t need his first wife’s consent to get married again.”

Zohreh Elahian, another principlist MP, even called the bill “progressive” and added that if Iran approves the bill, it doesn’t have to give in to international pressures to accept the convention on the elimination of all forms of discrimination against women.

To educate MPs and bring a spectrum of female opinions into the fold, women’s rights activists should meet regularly with their local representatives – male or female – and develop grassroots pressure on politicians, says Fatemeh Haghighatjoo, who served as a reformist MP from 2000-2004.

Fatemeh Haghighatjoo, who served as a reformist MP from 2000-2004, holding papers, poses for a lawmaker to take a photo after the parliament accepted her resignation.

Haghighatjoo left Iran in 2005 while facing a prison sentence for “inciting public opinion and insulting the judiciary,” but remains an active supporter of the women’s rights movement in her home country. “We have to see how we are more useful,” she said in 2009 of her self-imposed exile.

While she notes that the number of female candidates is higher than in the previous election, in 2012, Haghighatjoo predicts that political differences will challenge the unity of the women who fill the seats of Iran’s next parliament.

“The female MPs of the next parliament are not going to think alike,” Haghighatjoo told Tehran Bureau. “But I think they are going to agree on most of the issues related to women. They just need to sit together and discuss all the matters together.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community