By Kambiz Foroohar

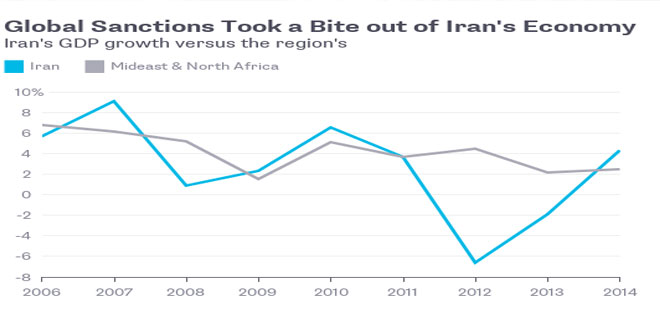

For a decade, the U.S. and other major powers squeezed Iran’s economy to force it to rein in its nuclear program. That’s over, at least for the moment. Now what? An unshackled Iran has plenty going for it.

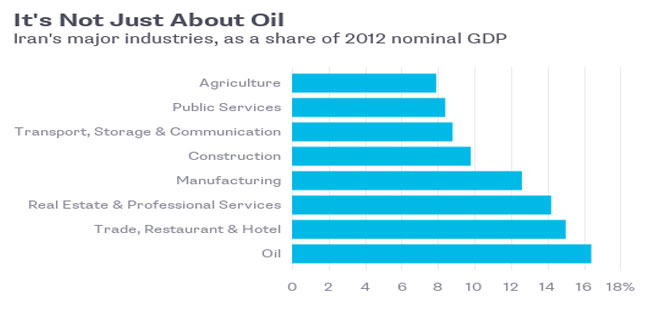

Like its relatively well-educated workforce, a wider range of industries than most oil exporters and a

president determined to liberalize the investment climate and revive the nation’s fortunes. Yet hardliners within the Islamic regime threaten to derail his agenda, and investors remain jittery over U.S. sanctions that are still in place. At stake is more than Iran’s gross domestic product. Its prosperity will affect the role Iran plays in the world’s most volatile region.

The Situation

International sanctions were lifted in January after inspectors certified that Iran curtailed its nuclear program as promised under a 2015 agreement with world powers. Iran’s moderate president, Hassan Rouhani, is courting global companies with the aim of doubling foreign direct investment in 2016 to about $15 billion. Overseas oil and construction companies as well as airplane and car manufacturers like Airbus and Peugeot Citroen have inked deals. But a U.S. restriction on dollar-denominated trades involving Iran has inhibited the sealing of additional agreements. A sweeping 1995 U.S. ban on trade and investment, triggered by concern about Iran’s links to terrorism, will keep most U.S. companies on the sidelines. However, Boeing gained U.S. government approval to sell to Iran as it negotiated a deal for as many as 109 jetliners.

The Background

The Pahlavi monarchy that ruled Iran from 1925 transformed a small agrarian economy into a booming one that included both manufacturing and major oil production. Rapid modernization, however, fueled a backlash that led to the 1979 revolution. Subsequent leaders have never quite settled on the appropriate shape of the economy in an Islamic state. At first, much of the economy was nationalized. Starting in the late 1990s, the country’s leaders tried privatization. Many assets, however, ended up either with the Revolutionary Guards, Iran’s premier security corps and the most powerful economic actor in the country, or with its affiliated corporations or religious charities. Elected in 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad took a populist turn, expanding credit, spending freely and handing out $15 a month in cash to every citizen. These policies fueled inflation just as sanctions began to bite. Rouhani was elected in 2013 promising to end Iran’s economic isolation.

The Argument

Can Iran’s economic revival succeed, and should the rest of the world want it to? The International Monetary Fund expects gross national product to grow by at least 4.5 percent in 2016. The low cost of producing crude in Iran (a third the cost in the U.S.) makes investing in its oil industry attractive even in an era of cheap prices. The auto industry, which made Iran the 13th largest producer of vehicles in 2011, is another draw. A fifth of the labor force is college-educated, twice the percentage in Brazil and India. Iran invests heavily in science-oriented education and research. Rouhani’s opening to foreign investment, however, rankles Iran’s radical theocrats, who are skeptical of Western capitalism. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, whose consent Rouhani requires for major decisions, sometimes sides with them. For investors, there’s always the risk that Iran will violate the nuclear deal, in which case sanctions are supposed to snap back. Some in the U.S. and Europe think that supporting Iran’s economy — about the size of Austria’s — is the best way to boost political moderates represented by Rouhani. They say that better integrating Iran into the global economy will create incentives for the country to abide by the nuclear agreement and other international norms. Skeptics argue that such thinking underestimates the commitment of Iran’s leaders to expanding their power in the region. They say an Iran with more money is just a more dangerous Iran, better able to support allies such as Syrian dictator Bashar al-Assad as well as militant groups like Hezbollah, Hamas and Iraq’s Shiite militias.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community