by:Kate Briquelet

Authorities say an Iranian royal living in Ohio was spending big bucks while misusing food stamps and Medicaid—but the prince claims he’s name-rich and cash-poor.

The wealthy son of an Iranian prince is under investigation for food-stamp fraud in Ohio, authorities say.

But Ali Pascal Mahvi, a 65-year-old businessman who lives between St. Lucia and Geauga County, claims he’s innocent.

On Friday morning, police raided Mahvi’s six-acre residence, hauling away computers and boxes of documents from his $800,000 mansion in Russell Township. Local TV footage zoomed in on his in-ground swimming pool, horse stable, and garage with luxury cars, including a BMW and Lexus convertible.

It’s outrageous to see a situation where somebody is living in a house almost worth a million dollars, a horse barn, driving luxury cars, have millions of dollars in overseas bank accounts and here they are accepting this type of assistance,” Geauga County prosecutor James R. Flaiz told WKYC, which first revealed the raid.

“Certainly, they were very good at manipulating the system,” Flaiz added.

Prosecutors claim Mahvi is a millionaire who gamed the system for two years to snag $300 a month in food stamps—or $8,358 to date, authorities say—as well as Medicaid for his wife and three adult children.

They say the American descendent to royalty has a Swiss bank account worth $4 million—an allegation Mahvi steadfastly denies. (Mahvi told The Daily Beast the account belongs to his late father, Abolfath Mirza Mahvi, and that the money was stolen by his dad’s business executives long ago.)

Cops are probing Mahvi’s bank accounts in an attempt to prove his cries of poverty were all a ploy. Investigators say the family has at least 14 bank accounts with a combined value of more than $4.2 million, WKYC reported.

As the family got food stamps from March 2014 to February 2016, they were also spending on $200 meals at local restaurants and $350 for cable TV, along with transactions at Starbucks and tanning salons, investigators say.

The food stamps were cut off in February “due to discrepancies in the family’s actual monthly income,” according to an affidavit for a search warrant.

But the Persian prince, who goes by “Pascal” and has not been charged with a crime, vehemently denies the allegations against him.

When reached by phone Thursday, Mahvi said, “We’re not guilty. This is total fabrication.”

Mahvi says he qualifies for food stamps because he’s fallen on hard times—stemming from a lawsuit from a former business partner—and that his only “income” is loans from friends helping him get back on his feet. (The Daily Beast could not confirm the existence of the lawsuit by press time.)

The bank, Mahvi says, owns his house.

“They’re saying I have $4 million in a Swiss bank account, that I’m defrauding the government with food stamps. It’s totally ridiculous,” he said.

They weren’t armed with all the facts, and they made a lot of assumptions and they’re false,” Mahvi added.

Mahvi, a developer behind the St. Lucia resort that is now the celebrity-studded Sugar Beach, said he can’t buy or rent another house because of bad credit. He also said that banks won’t lend him money because his home and his land is mortgaged.

“The cheapest thing for me to do and save my family, where I’m working to get myself back on my feet, is to borrow from friends. To pay Wells Fargo so we’re not in the street,” he told The Daily Beast. “That’s the only option I’ve got.”

According to Mahvi—who says he’s land-rich but cash-poor (he estimates his worth at $111 million for land he partially owns in St. Lucia)—he’s only guilty of failing to provide documentation of his loans to the county’s Jobs and Family Services department. He had no idea such paperwork was required, he said.

“I’ll bet you my bottom dollar—that I don’t have—that this is the only case like it in the whole country,” Mahvi said. “People who get food stamps usually can’t borrow [from wealthy friends]. We must be the only family in the U.S. that has the ability to borrow and yet qualify for food stamps.”

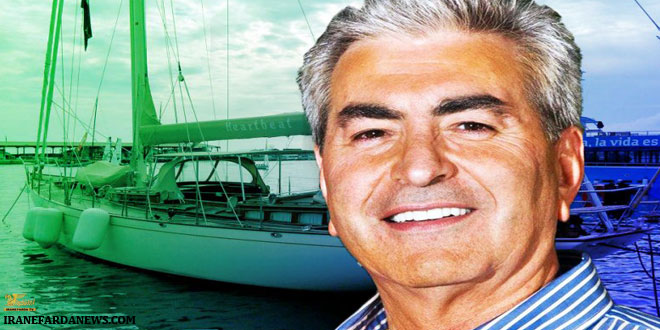

Mahvi’s use of food stamps contradicts the images of wealth littering his Facebook page: yachts and sunsets in St. Lucia and sailboats in Spain.

Investigators say the family’s bank records showed a monthly net income ranging from $3,200 to more than $8,500, according to WKYC. (Mahvi said that cash came as loans or church donations to his family and cannot be counted as income, per federal regulations.)

When Mahvi first filed for food stamps in April 2014, he listed his total net income after taxes and housing costs as zero, WKYC reported. Meanwhile, his cash, savings and checking accounts were less than $100, investigators said in the search warrant affidavit.

The application provided 2012 tax returns showing a negative income of $2.9 million, a search warrant affidavit states. Tax returns for 2013 and 2014 also showed negative income of about $3 million per year, the affidavit says.

In a second application for Medicaid, filed in June 2014, Mahvi indicated he expected to earn more than $300,000 in the next year from his company Idria Energy, and his interest in a Caribbean resort, the affidavit states. (The court document does not confirm whether Mahvi made the $300,000.)

Mahvi’s wife claimed an income of $1,200 in rental fees and $1,700 in “other income,” but it wasn’t disclosed when the family filed for food assistance, investigators say.

In April 2015, the family claimed zero income when they reapplied for Medicaid. That application was approved for one year, WKYC revealed.

But a county investigator allegedly found a pattern of lavish spending in bank statements and an unreported monthly income that allowed it.

According to an affidavit, the Mahvi family net income, based on bank records, was “well over” the maximum amounts approved for food stamps and Medicaid during six months they received assistance.

Authorities also pored through debits made to seven of the Mahvis accounts and tallied their spending on restaurants, Redbox, iTunes, alcohol, and other non-essential transactions.

The affidavit states all monthly spending, excluding three months, went over welfare limits. For example, in April 2014, the Mahvis dropped $9,867 on non-essential and non-business related items, and in November 2014, the family burned through $14,289, the affidavit says.

The most they spent was $16,727 in January 2016, the document states.

Detectives also claim to have unearthed “structuring” bank transactions, or transactions made in specific amounts to avoid federal reporting requirements. Investigators say six deposits totaling $30,000 were made in increments under $10,000 into the Mahvis’s money market account at Huntington National Bank from February 2014 to May 2014.

According to the affidavit, the Mahvis deposited $4,000 at 2:55 p.m. on Feb. 4, then $6,000 at 2:57 p.m., and they twice made similar dual transactions over the next few months, authorities say. (Banks are required by law to report transactions over $10,000 to the federal government.)

The county began investigating Mahvi this year after he asked a welfare official a question that raised suspicions, WKYC reported.

For his part, Mahvi says his loans from friends go to his $4,600 mortgage, car insurance, pet food for seven dogs, two cats, and two horses (“What are we going to do with the animals, put them down?”), and $500 cellphone bills, which are high because he makes international calls for work. Some of his dining expenses are business-related, he says.

“Sometimes I have to meet people, so I go to restaurants and I pay the bill because I’m self-employed,” Mahvi said, adding that he’s now trying to pay his debts by getting into the fuel business.

Mavhi said the stress over his financial ruin led to him having a heart attack in June.

Three months later, he said, cops bombarded his home at 10 a.m. with guns drawn on him and his son, and TV cameras were along for the ride.

“At the end of the day, there’s nothing left,” Mahvi said. “We live hand to mouth every day. I’m so fed up and so tired of fighting. This thing happened and knocked the wind out of me.”

Mahvi thinks people should focus their outrage on the regulations that allow him to receive welfare benefits. “Federal laws say loans are not income and not reportable,” he said. “In other words, in this country, I could borrow a million from you today and still be on food stamps.”

Requests for comment from the Geauga County prosecutor’s office, and the county’s Jobs and Family Services investigator, were not returned Thursday.

The allegations are just the latest road bump for Mahvi, who wrote The Deadly Secrets of Iranian Princes, a memoir about his upbringing within the Shah of Iran’s inner circle after his father became a chief adviser.

Born in New York, Mahvi moved to Iran to work and spend time with his father after he graduated from college, but they fled after the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

Mahvi says he was on a death list from 1980 to 1990 for Crimes Against God, because he previously, and unwittingly, was engaged to a Playboy bunny. “The clergy there put a fatwa on me to have me killed,” he said.

In 1981, the prince met his wife, the daughter of a local police chief, in Cleveland. They stayed in Ohio, and he traveled for work, accumulating an airplane and yacht before his wealth allegedly fell apart.

His new energy venture is his last shot to save his family home, he says.

“I am a real prince. I do not use the title,” Mahvi said. “But I’m not a millionaire.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community