By Robin Wright 19 October 2016

The first season of “House of Cards,” the Netflix series about the demonic American politician Frank Underwood and his duplicitous wife, Claire, recently made its début on Iranian television, just in time for the finale of the American elections. The show has been dubbed in Farsi—as “Khaneh Poushaly,” or “House of Straw”—by a state-run television channel. It ran every night for two weeks. The timing seemed deliberate, and authorized from the top: the Islamic Republic vigorously censors most American programs, and the director of Iran’s broadcasting authority, I.R.I.B., is appointed by the Supreme Leader.

Among hard-liners, the response to the series has been gleeful. It fits their profile of the United States as the Great Satan. Mashregh, a Web site linked to the Revolutionary Guards, commented, “House of Cards has skillfully shown the deception in the complicated political sphere of liberal American civilization, as well as the treason, power-hungriness, promiscuities and crimes behind those ruling in the country.”

Iran’s media has generally been obsessed with the upcoming American contest, even more than with the country’s own Presidential election, scheduled for next May. Mashregh has an entire page devoted to it. For the first time, Iranian television broadcast an American Presidential debate live, in simultaneous translation—the October 9th encounter, in which Donald Trump denied sexually assaulting women and threatened to put Hillary Clinton in prison if he is elected.

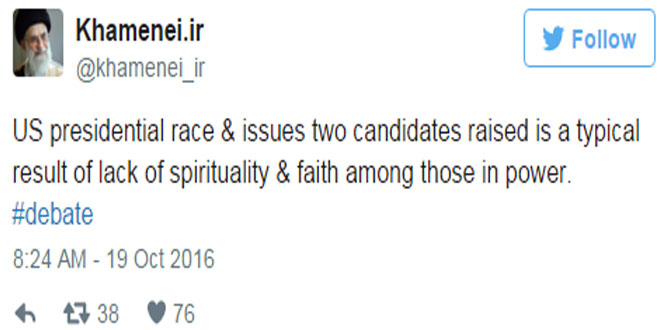

Even the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei weighed in on Twitter:

Foad Izadi, a conservative analyst who is a member of Tehran University’s Faculty of World Studies, told me that the authorities allowed the broadcast “for the same reason they ran ‘House of Cards’: Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton are both seen as manipulative, corrupt, and dishonest, engaging in unethical behavior in both their personal and political lives.”

Iranian newspapers are running front-page caricatures of Trump and Clinton to illustrate stories about their accusations against each other. The video of Trump’s salacious conversation with the “Access Hollywood” host Billy Bush, from 2005, made the front pages of nineteen Iranian newspapers. “Is This the End of the Populist?” a headline in Jahan-e Eqtesad asked.

Trump’s allegations that the U.S. election is rigged have particularly resonated across Iranian media. The coverage is, in some ways, revenge. In 2009, the reëlection of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was marred by widespread allegations of fraud. The ensuing Green Movement demonstrations were the longest and most contentious challenge to the theocracy since the 1979 revolution. Millions turned out in the streets of cities across the country; the protests, which were sparked and sustained by social media in Iran, endured, sporadically, for more than six months. Supreme Leader Khamenei vehemently denied that the election was rigged, and charged instead that foreign agents had launched a “velvet revolution” to oust the regime.

As evidence, Khamenei’s Web site cited a 2009 speech that Clinton gave, as Secretary of State, at Georgetown University. “We can help change agents gain access to and share information through the Internet and mobile phones, so that they can communicate and organize,” Clinton declared. She went on, “With camera phones and Facebook pages, thousands of protesters in Iran have broadcast their demands for rights denied, creating a record for all the world, including Iran’s leaders, to see. I’ve established a special unit inside the State Department to use technology for twenty-first-century statecraft.”

In Tehran today, a Clinton Presidency is viewed as simultaneously reassuring and unnerving. She would represent continuity on the nuclear deal (“We have offered to negotiate directly with the government on nuclear issues,” she said at Georgetown), but she has also expressed “solidarity with those inside Iran struggling for democratic change,” which both frightens the regime and infuriates it.

As for Trump, hard-line media outlets and reformist ones alike have portrayed him as a buffoon. Cartoons highlighting his orange skin and matching pompadour rival any in the American press. Fars, a semi-official news agency, superimposed Trump’s face on the Statue of Liberty; instead of holding a torch, he is thrusting an assault rifle into the air. Skulls lie at his feet. Another Fars cartoon shows him sitting atop the G.O.P. elephant and choking it.

For Tehran, the most important prism on the U.S. election is the fate of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, as the nuclear deal is known. A weekly business magazine, Tejarat Farda, ran a cover story on Clinton and Trump asking, “Which is worse for the J.C.P.O.A.?”

“It is the U.S. President who decides to waive the Iran sanctions now and in the future,” Izadi told me. He said that, in the view of many in the Iranian government, both hard-liners and centrists, “Americans have not fully complied with the terms of J.C.P.O.A. And because of this Iran is not seeing the economic benefits of the agreement—another example of American politicians’ dishonesty.”

Tasnim, a publication associated with the Revolutionary Guards, published a caricature of Clinton with her mouth agape and a roll of toilet paper under her chin, threaded through a pearl necklace. The caption read, “Clinton says U.S. will react firmly if Iran breaks nukes deal even by one iota.” The toilet paper, presumably, implied that she was talking crap.

Trump’s initial pledge to renegotiate the Iran nuclear deal did garner support among hard-liners in Tehran, who opposed the diplomacy and the subsequent compromises with the outside world, particularly the United States. During the spring primaries, Hossein Shariatmadari, the editor of Kayhan, told a local news agency, “The wisest plan of crazy Trump is tearing up the nuclear deal.”

I asked Izadi to tell me what Iranians were concluding from the Presidential debates. “In general, U.S. foreign policy in the Middle East, U.S. relations with Israel, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and so forth, affect people’s lives here,” he replied. “So seeing how U.S. elections are conducted, how American politicians behave toward each other, and what they think about Iran and the rest of the Middle East are of interest to Iranians.” As for “House of Cards,” he said, “for people who begin with a negative view of American politicians, the series reinforces those ideas. I guess people realize that the U.S. political process is at least as complicated as the Iranian political process.” Besides, he said, “ ‘House of Cards’ is also a good show.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community