In Iran, the Wounds of the Revolution Reopen

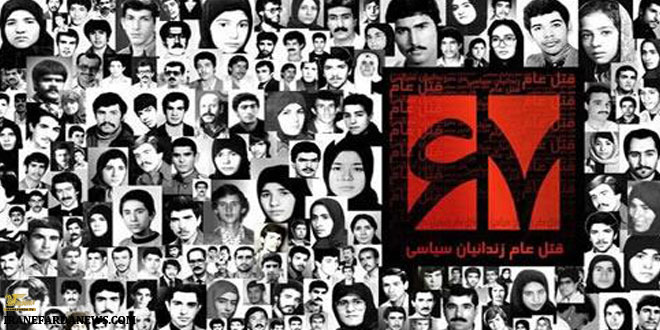

New Evidence of the 1988 Mass Killings

By Kasra Naji

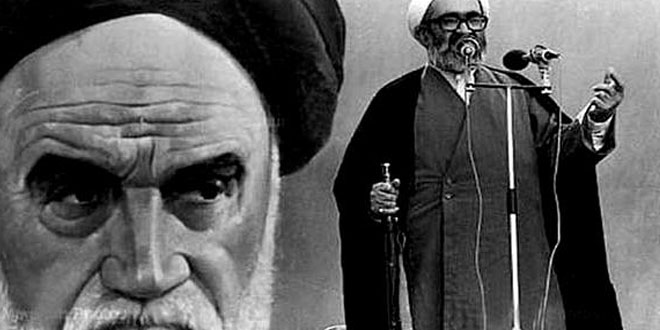

Iran’s Islamic Revolution of 1979 turned violent almost immediately after the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Dozens of top figures of the previous regime were captured, summarily tried, and executed by a firing squad, night after night, on the roof of a school where the leader of the revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, had taken residence in central Tehran.

The photographs of their bullet-riddled bodies, naked from the waist up, were published on the front pages of the newspapers. The message was clear: there was no going back to the previous era. The brutality shocked a nation previously unused to this level of violence, especially as those responsible were Shiite clergymen, men of God. But Iranians, still united in the revolutionary fervor that had just overthrown one of the most powerful regimes in the region, went along with it. In recent memory there was no precedent anywhere in the world for the clergy taking power. Nor was there a revolution on this scale. The revolution had to be protected.

Ayatollah Khomeini, with his flair for ruthlessness, laid the groundwork for a culture of endemic violence and impunity that have endured to this day. In the name of the revolution, this culture of violence led the country astray, earning it a reputation as a rogue state, stunting its development.

There are no shortages of examples of this brutality in the 37-year history of the Iranian Revolution—particularly in the first decade. But an audiotape from nearly three decades ago that has recently surfaced in Iran throws a spotlight on perhaps the most horrific episode of the country’s clerical rule.

The audiotape focuses on the events in the summer of 1988, when, on the order of Khomeini, thousands of political prisoners who had been sentenced to jail for political activities were executed in secret in a matter of weeks. The prisoners belonged to a variety of political groups, such as the Mujahideen Khalq Organization, or the MKO, and the leftist Fedayeen and Paykar.

In the audiotape, of a meeting on August 15, 1988, Khomeini’s then heir apparent, Ayatollah Ali Montazeri, is heard castigating members of the committee in charge of the executions, saying that history will judge them. “Let me be frank with you. You have committed the biggest crime in the Islamic Republic—a crime that will condemn us all in history. You all will be judged as the biggest criminals in history,” a furious Montazeri says during the meeting, which was held in his house in the holy city of Qom.

The committee members, all clergymen, had been summoned to report on the progress of their work. They informed Montazeri that they had executed 750 prisoners in Tehran alone and that there were another 200 or so executions in the pipeline. They didn’t know that Montazeri had sent two handwritten letters to Khomeini listing his reasons for his strong opposition to the massacres. “I didn’t want history to judge Khomeini as a bloodthirsty, brutal, and harsh figure,” he tells those present.

In the meeting, he asks the committee members, “How can you justify killing a prisoner who is in jail, already serving a sentence for what he or she has done? What does that tell us about our justice system?”

The clash over the executions led Khomeini to disown Montazeri a few weeks later and sack him as his heir apparent, paving the way for Ayatollah Ali Khamanei to become the supreme leader.

Montazeri died in 2009. The audiotape was posted on his website, which is run by his son, Ahmad, also a clergyman. He says he has since been ordered to take down the audiotape by Iran’s Intelligence Ministry, although it has already been widely shared on the Internet, including on YouTube.

The audiotape will give new ammunition to victims’ families, many of whom—28 years later—are still seeking justice, looking for where their loved ones were buried. Already there have been calls for an investigation into the murders.

Ahmad Montazeri has told BBC Persian Television that by publishing the tape, he wanted to put an end to efforts by those who have been distorting history as told in a 600-page memoir his father published online in 2000 while under house arrest.

The audiotape highlights not only the ruthlessness of Khomeini but also that of the members of the committee, some of whom still hold key positions today, including in President Hassan Rouhani’s cabinet.

The executions all took place in the space of roughly eight weeks after Iran repulsed the last incursion into its territory by the forces of the Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein at the end of the eight-year Iran-Iraq war. The war had already left a million people on both sides dead and injured. In the last months of the war, Iran was faring badly at the fronts and risked losing the war. Khomeini had just, very reluctantly, agreed to a UN-brokered cease-fire. But Saddam was keen to strengthen his position before the cease-fire came into effect. His forces made a last push into Iran, joined by the Iranian opposition forces of the MKO, exiled in Iraq at the time. The last incursion was repulsed by Iran. But Khomeini, who had said that agreeing to the cease-fire was “like drinking from a poisoned chalice,” turned his wrath on thousands of imprisoned members of the MKO and other left-wing political organizations serving sentences for opposition activities or for waging armed struggle against the Islamic government.

Khomeini wrote to officials calling for the immediate formation of a committee “to execute without mercy all those who remain loyal to their cause.”

In ordering the setting up of the committee, later dubbed the Death Committee by the opposition, Khomeini instructed its members, whom he had appointed, to deliver “swift” justice. He said those who insisted on remaining loyal to their cause were “mohareb”— people waging war against God—who had to be destroyed. “I hope with your revolutionary vengeance toward enemies of Islam you will earn the approval of God,” he said.

Dozens of survivors have recounted how committee members brought prisoners individually to a room, asking them whether they remained loyal to their opposition organization. Even if they said no, they would be asked a few supplementary questions: Would they be prepared to put the noose around the neck of their former comrades who refused to renounce their cause? Would they denounce their organizations and their comrades publicly, on national television? And would they be prepared to walk into a minefield at the fronts in defense of Islam? Leftist prisoners were asked whether they believed in Allah, whether they prayed or fasted during Ramadan. Many answered in the negative and were executed, as they had no idea of the underlying purpose of these questions. They had been told that they were being questioned only in order to segregate the prison wards according to believers and nonbelievers and their affiliations.

At least 4,482 young men and women disappeared during the two-month period, according to Amnesty International. Montazeri said he was told at various times that between 2,800 and 3,800 prisoners were summarily executed. Almost all were reportedly hanged inside the prison compounds to maintain secrecy. Middle East historian Ervand Abrahamian detailed in his 1999 book Tortured Confessions that the committee refused to use a firing squad because of the noise, even when the hangmen complained of the grueling labor involved in hanging so many.

The families of the executed were not told of the killings until several months later, when they were called in to claim the belongings of their loved ones, but even today do not know where they have been buried. Many believe the victims were left in mass graves whose whereabouts remain unknown. Some were buried in unmarked graves in a barren plot of land on the side of a highway leading out of Tehran. Even today, the families are harassed and prevented from holding an annual ceremony to remember their sons and daughters.

The story of the 1988 executions has been told by the families of the victims before. A people’s tribunal, presided over by respected international judges in London and in The Hague in 2012, investigated the murders and found the Iranian leaders during that time guilty of crimes against humanity. But the audiotape that has appeared on the Montazeri’s website allows the public to hear for the first time the voices of those responsible for the executions discussing their own actions—they have otherwise been have silent regarding their roles in the matter.

One member of the committee was Mostafa Pourmohammadi, then deputy intelligence minister. Today he is the minister of justice in Rouhani’s cabinet. In the past, he denied having a role in the mass executions. But now the audiotape places him in the room, where he is described by Montazeri, the second-in-command of the Islamic republic at the time, as one of top criminals in history.

Another of those present, Ebrahim Raeesi, was the deputy prosecutor of Tehran at the time. He is now a close confidant of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, who recently appointed him to head Astan Quds Razavi, the country’s largest charitable organization, which manages the Imam Reza shrine in Mashhad, the biggest Shiite shrine in the country. Some observers have even named him as a possible successor to the supreme leader.

Another member of the committee who was at the meeting in Montazeri’s home was Hussein Ali Nayeri. At the time, he was the religious judge at Evin Prison in Tehran, where many of the executions took place. He was by all accounts the most hard-line of the members of the committee and a favorite of Khomeini, who later gave him a promotion. Today he is a high court judge, having been the deputy head of the Supreme Court for two decades. He is heard on the tape trying to calm Montazeri, saying, “I assure you if anyone else were in charge, the figures”—the number of executions—“would be three times higher.”

The audiotape does not immediately damage Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei. Although he has time and again supported the idea of executing internal opponents of the regime, he was not directly involved.

The prison pogrom of the summer of 1988 came toward the end of the first decade of the Islamic Revolution, during which more than 12,000 people had been executed or disappeared. An international tribunal led by respected international judges heard the testimonies of many survivors and their families, some of which had lost multiple relatives. It found the leaders of Iran at the time guilty of crimes against humanity.

Those present at the meeting have not reacted to the publication of the audiotape, but one longtime senior clerical member of the Iranian judiciary, Ali Razini, has been quoted by the Fars news agency justifying the elimination of regime opponents at the time. “We had the courage to put our signatures to execution orders and we are proud of it,” he said.

In the past year, since Iran reached an agreement with the United States and other world powers to curtail its nuclear program, its human rights record has worsened, according to rights groups, as hard-liners in the judiciary fear they might lose power to the more moderate forces within government. Many journalists, as well as a number of dual nationals visiting their families in Iran, have been jailed—some as de facto hostages. Iran has also stepped up its executions. Human rights groups say Iran has executed at least 230 people since the beginning of 2016, including 20 Kurdish and Sunni prisoners for “enmity against God” this month alone. Nobel Peace laureate Shirin Ebadi, a human rights lawyer and former judge in Iran, has described the latest executions as alarming and reminiscent of the mass executions of the first decade of the revolution. Her own brother-in-law, who was only 17 when he was jailed for distributing an opposition weekly, was executed in the summer of 1988 after serving seven years of a 20-year sentence.

Mass executions subsided with the end of the Iran-Iraq War and the death of Khomeini. But the ayatollah’s decade in power left behind a lasting legacy of summary executions and abuse, endorsed by clerics in the judiciary, some of whom still think nothing of having the blood of thousands of their political opponents on their hands.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community