lobelog–

by Paul R. Pillar

There are several important things to understand about ballistic missiles and Iran, beyond the fact that this topic has become one of the latest on which those who want Iran to be an ostracized and feared pariah forever, and who still want to kill the agreement to restrict Iran’s nuclear program, have seized.

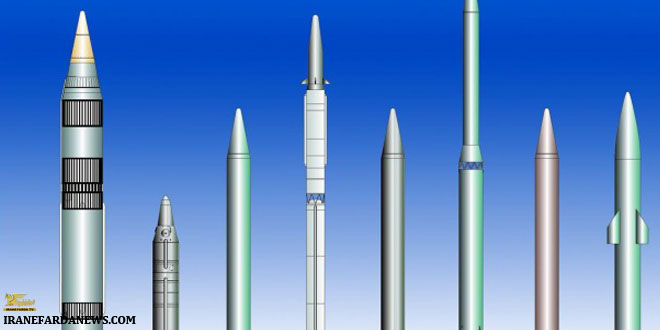

Ballistic missiles are any projectiles that follow, after an initial powered and guided phase, a ballistic trajectory. Devices with this name include an enormously wide variety of sizes, ranges, and capabilities. They run from short-range battlefield weapons to missiles with intercontinental range. Ballistic missiles are in the armed forces of many states. They have become important and accepted parts of the defense posture of many states. Most of those states do not have what are commonly called weapons of mass destruction, and the missiles in their arsenals are not intended or designed to be used with such weapons. Instead they are part of a standard conventional defense strategy. If there is a genie involved with ballistic missiles, it has long been way, way out of the bottle.

Scary rhetoric about Iran has repeatedly referred to the supposed prospect of an Iranian intercontinental ballistic missile, evidently to try to get Americans to believe that Iranian missile programs pose a threat to the United States. Such rhetoric bears little or no resemblance to what the Iranians have been doing in the way of development and testing of ballistic missiles. As missile expert Greg Thielmann, who studies the Iranian program closely, has concluded, an Iranian ICBM “is nowhere in sight.” Iranian work on missiles has focused on shorter-range systems that are more relevant to Iran’s defense needs within its own neighborhood.

Those needs, and how Iranian leaders perceive them, are shaped by a painful history of neighbors using ballistic missiles against Iran and by the prospect that missile-armed neighbors might use such weapons again. The Iran-Iraq war, begun by Saddam Hussein’s aggression against Iran in 1980, included several rounds of the “war of the cities” in which civilian populations were subject to bombardment from the air. Iraq used manned aircraft as well as ballistic missiles to attack Iranian cities, but during the later phases of the war the destruction of cities came mainly from Iraq’s missiles. It is impossible to come up with an accurate figure of losses sustained by these missile strikes amid what was a very bloody war overall, but probably in even just the first round of the war of the cities in 1984, civilian casualties numbered in the tens of thousands.

In the Persian Gulf region it was Saudi Arabia that made the single biggest move in the proliferation of ballistic missiles: its then-secret purchase in the 1980s from China of intermediate-range CSS-2 missiles. Today, Iranian leaders look across the Gulf at their regional rivals in Saudi Arabia and see a substantial missile force incorporating technology from China and Pakistan. It would be a non-starter for any Iranian leader, regardless of his politics or ideology, to disavow continued efforts to try to improve and develop Iran’s own force.

Additional confusion from the sort of rhetoric one hears today concerns exactly how missiles do and do not relate to the recently concluded nuclear agreement. That agreement—one of the signal achievements on behalf of nuclear nonproliferation—was achieved only by the parties agreeing to focus on the nuclear issue itself rather than wading into other grievances that the parties have against each other. Those include not only Western grievances against Iran but also Iranian grievances against the West and the United States, some of which have to do with U.S. military activities in Iran’s immediate neighborhood. Missiles, like a lot of other issues that each side may have otherwise been anxious to raise, were not the target of the nuclear agreement.

Despite frequent references today to Iranian missile tests as a “violation,” they do not constitute any violation of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (i.e., the nuclear agreement) or of the two-year-old preliminary agreement. In fact they do not involve a violation of anything that Iran has agreed to. Iran has never been under any obligation to help sanction itself.

And it is only as sanctions that the issue of missiles legitimately comes up at all in connection with the nuclear agreement. An embargo on export to Iran of missile-related materiel and a variety of other types of conventional armaments was part of a host of nuclear-related sanctions specified in a series of resolutions of the United Nations Security Council enacted prior to the beginning of the negotiations that led to the JCPOA. So was a call in a resolution in 2010 for Iran itself not to engage in missile development activity. All of these sanctions, like the other nuclear-related sanctions, were intended to induce Tehran to negotiate restrictions on its nuclear program. In that respect they were no different from sanctions involving banking access or pistachio exports. The missile-related sanctions had the added purpose of freezing or retarding any possible development of Iranian missiles that could be used to deliver nuclear weapons, as long as there was not yet an agreement precluding Iran from producing the fissile material that would be needed for such a weapon.

Now there is such an agreement. The reason for the nuclear-related sanctions no longer exists. If the principle of ending nuclear-related sanctions in return for Iran accepting the tight restrictions and intrusive monitoring provided for in the JCPOA were to be completely observed, then all of those sanctions—including the ones involving missiles—would end once Iran completes, which it might as early as the next couple of months, the measures it is obliged to complete before the accord is implemented. But somewhere along the line the subject of missiles and conventional armaments acquired a life of its own, with political pressure especially on the U.S. side not to give up those sanctions any time soon no matter what Iran does to dismantle key parts of its nuclear program. Thus there ensued some of the toughest negotiations before the JCPOA could be completed. In what has to be considered a major concession by Iran, it finally was agreed to let the embargo related to missiles run for another eight years, and the one covering other conventional arms five years. These are still all nuclear-related sanctions, even if their removal is being delayed despite Iranian compliance with the nuclear agreement.

International efforts, and not just those aimed at Iran, to restrict development of ballistic missiles always have been motivated by concerns about missiles that could be used to deliver weapons of mass destruction and especially nuclear weapons. That concern has been the focus and rationale of the Missile Technology Control Regime, the principal international effort to check the proliferation of advanced ballistic missiles. Iranian ballistic missiles pose no threat to U.S. interests as long as Iran does not have the fissile material to build nuclear weapons that could be put atop any of those missiles. Preventing such a nuclear capability is, of course, what the JCPOA is all about. It thus would be a stupidly counterproductive approach to let issues about missiles endanger the implementation and longevity of the JCPOA.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community