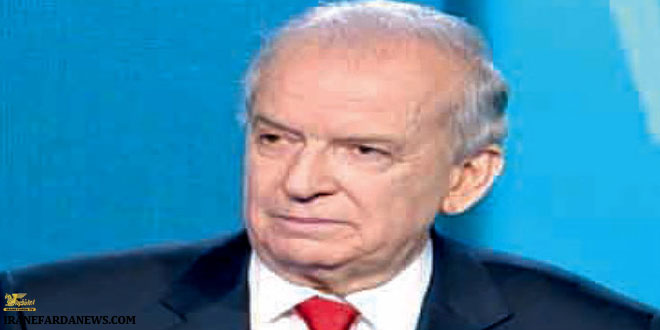

Marwan Hamadeh is uniquely placed to explain complex situation that Lebanon is going through, with country unable to elect president.

by:Mohamed Kawas

Beirut – Sitting with Marwan Hamadeh, it is clear that you are meeting a unique figure in Lebanese politics. Hamadeh has had a number of ministerial portfolios under several prime ministers and has played a pivotal role in Lebanon’s modern history.

He is uniquely placed to explain the complex situation that Lebanon is going through, with the country unable to elect a president and parliamentary elections on hold.

Hamadeh lived through Syrian tutelage over Lebanon, as well as the rise of the rival March 8 and March 14 blocs. Walid Jumblatt’s Progressive Socialist Party, of which Hamadeh is a member, had initially been a part of the March 14 alliance but left the coalition in 2011.

Jumblatt famously described the March 14 alliance as being more like an “atmosphere” than a coalition of parties. Hamadeh concurs, although he said he remembers the atmosphere that surrounded the “popular revolution” and the rise of March 14 clearly.

“This was not just a protest against the assassination of one of the pillars of Lebanon, prime minister Rafik Hariri. It was a protest against the use of assassinations by the Syrian regime in Lebanese politics — a policy that dated back decades,” Hamadeh said.

“Everybody was fed up with the Syrian presence in Lebanon. Over the years, their military presence declined, while their interference in Lebanese politics only increased,” he added.

Following Hariri’s assassination and the Cedar revolution, Syria’s presence in Lebanon ended on April 30th, 2005.

More than 11 years later, Lebanese politics is more divided than ever, with rival political coalitions unable to agree on the election of a new president to replace Michel Suleiman, who left office in May 2014.

More recently, it seemed the deadlock might be close to being broken after an unexpected agreement between Lebanese Forces leader Samir Geagea and rival Free Patriotic Movement leader Michel Aoun. They had been rival candidates for the presidency, which must be held by a Maronite Christian, although the latest agreement saw Geagea — who is part of the March 14 alliance — endorse Aoun — a member of the Hezbollah-led March 8 alliance — for the post.

Despite this, Hamadeh said he did not fear this resulting in a wider schism between Muslims and Christians.

“I do not fear this because Saad Hariri is not, and has never been, sectarian and he has confidence that Samir Geagea, who has experienced alliances with Muslims before, is committed to this,” he said.

As for whether he understands Geagea’s decision to endorse Aoun, Hamadeh said: “No, I do not understand his position, nor do I understand, or accept, Lebanon reaching a position where the only two candidates for the presidency come from within the March 8 alliance.”

The other candidate for president is Suleiman Frangieh. Despite also being a member of the rival political coalition, his candidacy has been endorsed by Saad Hariri in what represents another strange political alliance. A Frangieh presidency, however, would see Hariri retake the post of prime minister.

The latest presidential developments have also raised fears about Iran’s influence in Lebanon, particularly its backing for Hezbollah and the March 8 alliance. Hamadeh dismissed fears that Tehran could be able to take control of Lebanon, stressing the unique nature of Lebanese politics, which is almost defined by a philosophy of contrariness or defiance.

“Even if those allied with Iran took over the government tomorrow and elected a president and had a parliamentary majority, they still would not be able to change the inherent nature of Lebanon’s pluralistic system, which… prevents one party from dominating any other,” Hamadeh said.

However, he did warn that the current system is creating a dangerous sectarian atmosphere in which Lebanon and the Arab world’s Shias are concerned about being isolated and marginalised, an atmosphere that is being exploited by Iran.

Hamadeh stressed that, historically, Arab Shias have taken important positions in support of Arab causes and that the recent sectarianism can be traced to the Iranian revolution. “We did not know a change of regime in Iran would affect the entire region in this way and they are using the wilayat al-faqih [Guardianship of the Jurist] concept to take the Shias away from us,” he said.

Wilayat al-faqih is a Shia concept that states that a jurist, in this case the supreme leader of Iran, must be in charge of worldly affairs, including politics. It is a concept to which Hezbollah and other groups subscribe.

As for Hezbollah’s obstruction of the election of a new president, he said: “Hezbollah wanted a consultative summit to change the political system in Lebanon, but this idea was revoked because the Christians fear the country returning to a numerical, not pluralistic, system.”

“Hezbollah does not want a president, not out of fear of Suleiman Frangieh, for he is of no concern to them, but rather to prevent the early rise of Saad Hariri [as prime minister]. They are exerting all their efforts to postpone this,” he said.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community