by Esfandyar Batmanghelidj 1st January 2018

In February of 2017, I wrote about Iran’s “forgotten man,” the member of the working class who seemed invisible in the talk of the country’s post-sanctions recovery:

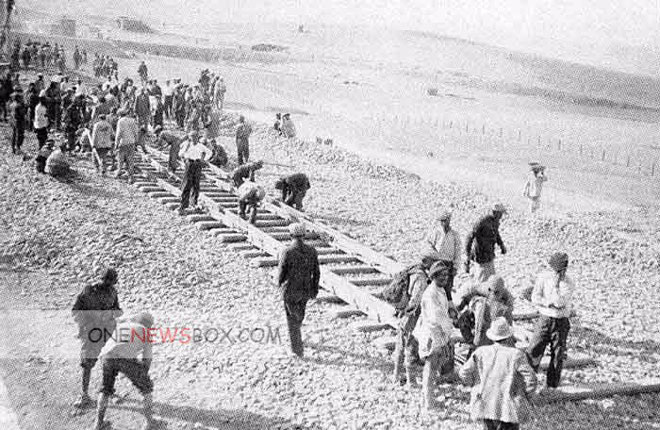

What has been lost is an appreciation that the “normalization” of relations between Iran and the international community is as much about elevating “normal Iranians” into a global consciousness, as it is about matters of international commercial, financial, and legal integration. While there has been progress in building awareness of Iran’s young and highly educated elite, whose start-ups and entrepreneurial verve play into the inherent coverage biases of the international media, a larger swath of society remains ignored. By a similar token, the rise of the “Iranian consumer” with untapped purchasing power and Western tastes has been much heralded, but the reporting fails to appreciate that Iran’s upper-middle class rests upon a much larger base whose primary economic function is not consumption, but rather production.

With the new wave of protests sweeping Iran, it seems that the country’s forgotten men and women may be mobilizing to ensure their voices are heard in Iran and around the world. There is a growing consensus that the protests are comprised primarily of members of the working class, who are most vulnerable to chronic unemployment and a rises in the cost of living.

The idea that these are working class protests has explanatory power. First, if the protests are indeed a working-class mobilization, then they are less surprising, and can be seen as akin to the regular “bread riots” that took place during Ahmadinejad’s second term, when Iran’s economy suffered its sharpest contractions.

Second, a working class outlook may explain why the political slogans and imagery of the Green Movement have not been deployed by the protestors. The Green Movement was a predominately middle class movement focused on civil rights, which emerged in response to a chosen candidate being fraudulently denied an election victory. Solidarity with lower class voters was limited and economic grievances were not a central focus.

Third, such a demographic composition may explain the support conservative political groups in Iran have given to the protestors, despite the spectacle and soundtrack of anti-state slogans that have marked many of the gatherings. Conservative politicians are being careful not to alienate members of their base, while trying to cast the protests the predictable outcome of Rouhani’s economic policies. Moreover, a working class composition of the protests can explain how exactly Iran witnessed a successful presidential election with historic turnout and a clear victor just six months before mass mobilizations in cities across the country to protest the government. It may be that those turning to protest now feel their voice was not heard in the May elections.

A simple comparative review of upper-middle income countries such as Iran—including Brazil, Mexico, Thailand, and Russia, among others—demonstrates that while protests end with political expressions, they usually begin with economic motivations. That Iran’s working classes are ready to mobilize, and that the mobilization was so quick, makes sense within the context of Iran’s current economic malaise.

It is generally overlooked when discussing Iran’s post-sanctions economy that Rouhani has operated an austerity budget since his election in 2013. Some even describe his policies as “neoliberal.” While an imperfect descriptor, his administration’s economic approach does broadly correspond to the neoliberal “Washington consensus,” which seeks economic reform through trade liberalization, privatization, tax reform, and limited public spending, focus on foreign direct investment, among other policies.

Such an economic approach is in many ways understandable. Rouhani is seeking to correct the populist excesses of the Ahmadinejad administration while also addressing longstanding structural issues in Iran’s economy such as its overextended welfare system, a reliance on state-owned enterprise, and cronyism and corruption. But these are, by dint of difficulty, long-term reform projects, which may not fully cohere until after Rouhani’s tenure has ended. In a way, it is laudable that the administration is applying such an outlook for the benefit of what Homa Katouzian has called a “short-term society.” But the near-term political costs are becoming clear.

Rouhani’s budget is ultimately ill-suited to addressing the economic imperative of job creation, which is urgent and at the heart of popular dissatisfaction. As economist Djavad Salehi-Esfahani has written in response to Rouhani’s most recent budget:

One of the main stated goals of this budget is to create jobs, but it is hard to see how it can do that by slashing the development budget at a time that interest rates are very high (they exceed inflation by 5 percentage points or more). The unemployment rate has been rising in the five years that Rouhani has been in office, mainly because of increased supply pressure, but low demand has been an equal culprit. With unfavorable news about the future of the nuclear deal and the removal of sanctions, thanks to the 180-degree turn in US policy toward Iran, the prospects for a foreign-investment driven recovery are dim. With public patience running low, the debates in the parliament over this budget should be more serious than the usual haggling over the needs of special interests.

Most governments in Rouhani’s position pursue expansionary monetary policy and boost public spending to try to drive investment and economic growth. But Iran faces a series of economic challenges that complicate such a response. For example, the principle economic achievement of the Rouhani administration has been to bring inflation under control. The International Monetary Fund expects inflation to sit below 10% this year, down from 40% in 2013. Controlling inflation is critical to bringing stability to prices in Iran’s basket of goods, where other market forces continue to drive up prices. Any attempt to pump money into Iran’s economy to spur investment risks undermining the success on inflation.

Additionally, in the face of low-growth, central banks commonly lower interest rates to make it cheaper to finance new investment. But Iran’s interest rates are being slowly rolled back from a high of 22% to the present level of 18%. Slow adjustments are necessary due to Iran’s banks being overleveraged. Reducing the interest rate too drastically, especially as inflation remains stubborn, would have two effects. First, savers would see their deposits lose value. This would predominately hurt lower-income savers who have a less diversified range of assets. Members of the middle class still benefit from asset appreciation in still robust categories like real estate, stocks, or even gold. Middle class fortunes have improved somewhat following the nuclear deal for this reason. On the contrary, members of the working class rely on interest-bearing deposits accounts to conserve wealth and are therefore very vulnerable to fluctuations in interest rates. The controversy over the unsustainable interest rates offered by unlicensed savings and loan institutions, which spurred protests in cities across Iran in the summer 2017, is indicative of the vulnerability.

Second, a lower interest rate would threaten the financial wellbeing of many of Iran’s banks, which have long skirted reserve ratios and amassed toxic debt. Any attendant drop in deposits would make it even harder for banks to shore up their reserves, making politically fraught recapitalization by the central bank more likely. In the recent assessment of Parviz Aghili, CEO of Iran’s Middle East Bank, it would cost as much as $200 billion to bring Iran’s $700 billion balance sheet in compliance with Basel III standards, which call for a minimum leverage ratio of 6%. By comparison, Rouhani’s total budget for the next Iranian calendar year is $104 billion.

In the face of limited options, the Rouhani administration believed that post-sanctions trade and investment, made possible by the sanctions relief afforded under the Iran nuclear deal, would enable the country to kick-start growth and investment that supports job creation. But the economic dividend of the nuclear deal has not materialized as anticipated. The majority of business leaders believe that this is primarily due to external factors, namely President Trump’s threats to re-impose sanctions on Iran, rather than Iran’s own challenging business environment. The nuclear deal has been so central to Rouhani’s economic plan, with the nuclear deal and investment deals basically conflated in much of the discourse, that the concern around the future of the nuclear deal has also hit confidence in Rouhani’s economic management at large.

Overall, Rouhani is running an austerity budget because he is between a rock and a hard place. The policies he is adopting are economically sensible and necessary—so much so that the budgets have been passed despite pushback from parliament and other corners of the Iranian power structure as to the approach, neoliberal or not. But the policies are politically costly, testing the patience of a people who feel that the hopes for a better livelihood slipping away as the years pass. As Mohammad Ali Shabani writes, the circumstances in Iran can be described by the concept of the J-curve, which posits that mobilizations occur “when a long period of rising expectations and gratifications is followed by a period during which gratifications … suddenly drop off while expectations … continue to rise.”

We cannot fault Iranians for their rising expectations, for they are a people who know their immense potential. This is especially true of the working classes, who have built Iran’s diversified economy with their labor and the country’s rich culture with their values. As Iran has grown richer and more advanced, the burgeoning middle class has come to represent the future. But the recent experiences of wealthier economies offer a cautionary tale about “forgetting” the working classes, and sacrificing their expectations to protect the gratification of others.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community