It’s a rivalry rooted in esoteric religious debate, but this clash – between the two most dominant figures of Shiite religious authority – promises major consequences, both for Iran’s clerical establishment, and their influence over Shite around the globe. The most immediate impact is being felt in next-door Iraq – as it charts its own in the shadow of its neighbor.

It’s a rivalry rooted in esoteric religious debate, but this clash – between the two most dominant figures of Shiite religious authority – promises major consequences, both for Iran’s clerical establishment, and their influence over Shite around the globe. The most immediate impact is being felt in next-door Iraq – as it charts its own in the shadow of its neighbor.

Articles

Science Under Maximum Pressure in Iran

From travel restrictions and publishing bans to currency collapse, the restoration of US sanctions has left researchers in Iran reeling.

BY: DAVID ADAM Sep 13, 2019

As a research scientist, Shahin Akhondzadeh is used to having his papers questioned. But last year, he received a novel reason why a journal was unable to publish his work: his nationality. Akhondzadeh is Iranian and works at the Tehran University of Medical Science. And for the US-based journal and its publisher, that made him a persona non grata.

“A day after I submitted it they told me because you are from Iran we cannot publish this,” he tells The Scientist in a phone interview from Tehran. “We are used to having an unfair situation in politics. But to have an unfair situation in science is very bizarre.”

Akhondzadeh, an expert in psychiatric disease, had previously published in the journal and acted as a peer reviewer for it—and many others—with no concerns raised. And he says he is not the only Iranian scientist affected: medical journals across Europe and the United States are responding in the same way, “Because of the sanctions, we cannot process your manuscript.”

International sanctions against Iran—first imposed by the US after the 1979 hostage crisis and later by the United Nations—were lifted in 2016 after Iran agreed to limit its nuclear program. But President Donald Trump announced last year the US would withdraw from that deal, and restored US controls on trade with the country.

Officially, research activities such as publishing academic papers should be exempt from the restrictions—unless the author is a direct employee of the country’s government. But Akhondzadeh says publishers either don’t know this or they are unwilling to take the risk.

There is also a more practical obstacle that stops Iranian researchers from publishing their work: in November 2018, Iran’s central bank was disconnected from the main global system used to transfer money across borders. Many international banks have followed with their own restrictions and the resulting blockade on currency exchange makes it impractical for Iranian scientists to pay the publication fees required by many open-access journals (although some publishers such as BMJ Publishing Group have waived them).

Such de facto publishing embargoes are highlighted in a new analysis of the negative effects of the US political sanctions on international collaborations and research in Iran published earlier this week. The study—written by several Iranian authors in BMJ Global Health—found that Iranian researchers have been increasingly denied opportunities to publish scientific findings and attend scientific meetings during periods of increased sanctions. And they find it harder to access essential laboratory supplies and information resources.

Money in limbo

In additional to publishing fees, there are journal subscriptions to consider. Akhondzadeh says his university library is overdue on its fees to international publishers, and researchers there expect to lose electronic access to journals at any time. The university has the money and wants to pay its bill, he says, but can’t find a way to do so.

The same problem comes when trying to receive money from outside Iran. Joint projects with scientists in Iran have been suspended by the UK’s Wellcome Trust and the US National Institutes of Health, this week’s study says, because the promised funds can’t be transferred.

The Scientist found another example of stalled scientific endeavors. The International Biology Olympiad (IBO), an organization based in Germany that arranges events for school children, is sitting on $130,000 US collected in registration fees for a 2018 event in Tehran that it cannot transfer to organizers there.

“We have found no bank within the European Union that would enable us to transfer the money to Iran,” says Sebastian Opitz, head of the IBO office in Kiel. “As you can imagine, we as a public benefit organization find this situation highly troubling.” Banks have told him the only way to move the money is as cash. Opitz says his organization has so far refused because the lack of transparency is “unprofessional.”

Travel banned

One casualty of the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” hard line on Iran was a long-running program of the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NAS) that arranged bilateral meetings and organized exchanges of scientists between the two countries. Glenn Schweitzer, director of the NAS Office for Central Europe and Eurasia who ran the engagement program, says it closed down in 2017 when the increased political tensions between the US and Iran along with the Trump administration’s travel ban on residents from a number of Muslim-majority nations made it impractical.

See “As Visa Difficulties Persist, Scientists Push for Change”

Researchers in Iran have also found the travel ban is having a knock-on effect, with colleagues from Europe reluctant to visit because they fear an Iranian stamp in their passport could make it more difficult for them to enter the US. A prior trip to Iran prevents access to common visa waiver schemes that avoid the need to apply for a full US visa.

A biologist at University of Tehran, who wanted to remain anonymous to preserve privacy, says scientists there have resorted to asking colleagues in universities outside Iran to act as intermediates to get basic laboratory services routinely done abroad, such as DNA sequencing. Or they have asked friends traveling outside Iran to take the DNA samples with them and to mail them to the sequencing company from abroad. The biologist says a company that had accepted samples from Iran for sequencing in the past said that “political issues” made it difficult to deal with scientists in Iran directly.

Abbas Edalat, a British-Iranian computer scientist at Imperial College London, says it’s wrong to blame all of the untoward effects on research on President Trump.

“Even after the 2015 treaty, under Obama, there were all these limitations imposed by the United States on Iranians, including Iranian academics,” he says. Under President Barack Obama’s presidency, he says, the US State Department emailed him to say his membership of a visa waiver scheme, commonly used by many visitors to the US because it’s easier than applying for a formal visa, was being canceled because of his nationality. “It’s true that it has become much more accentuated under Trump—there is no comparison—but it all started under Obama.”

The biggest problem for Iranian scientists right now, he says, is the collapse of the country’s currency, the rial. “The budget they have for travel, to go to conferences, to even pay for articles to appear in conference proceedings has been so limited now because of the sanctions that they can’t afford to do that.”

See “Opinion: Broken Promises Caused by the Travel Ban”

Edalat, the founder of the Campaign Against Sanctions and Military Intervention in Iran, was arrested by security officials while visiting Iran in April 2018 and detained for eight months on suspicion of spying. He blames the US and its allies for what he says is understandable nervousness in Iran. “They have created a kind of siege conditions in Iran. All these US military bases surrounding the country and, apart from the sanctions, all these overt and covert operations for regime change. Any country in that kind of condition would have its intelligence services be over-cautious.”

Schweitzer says everybody suffers from the political stand-off. “The Iranians are very good scientific and engineering specialists,” he says. “Global science is missing a piece if the Iranians don’t participate.”

David Adam is a UK-based freelance journalist. Email him at davidneiladam@gmail.com and follow him on Twitter @davidneiladam.

The Secret History of the Push to Strike Iran

By Ronen Bergman and Mark Mazzetti – September 2019

In July of 2017, the White House was at a crossroads on the question of Iran. President Trump had made a campaign pledge to leave the “terrible” nuclear deal that President Barack Obama negotiated with Tehran, but prominent members of Trump’s cabinet spent the early months of the administration pushing the mercurial president to negotiate a stronger agreement rather than scotch the deal entirely. Thus far, the forces for negotiation had prevailed.

But counterforces were also at work. Stephen K. Bannon, then still an influential adviser to the president, turned to John Bolton to draw up a new Iran strategy that would, as its first act, abrogate the Iran deal. Bolton, a Fox News commentator and former ambassador to the United Nations, had no official role in the administration as of yet, but Bannon saw him as an outside voice that could stiffen Trump’s spine — a kind of back channel to the president who could convince Trump that his Iran policy was adrift.

As a top national security official in the George W. Bush administration, Bolton was one of the architects of regime change in Iraq. He had long called not just for withdrawing from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or J.C.P.O.A., as the 2015 nuclear deal was known, but also for overthrowing the Iranian regime that negotiated it. Earlier that July, he distilled his views on the matter in Paris, at an annual gathering in support of the fringe exile movement Mujahedeen Khalq, or the M.E.K., which itself had long called for regime change in Iran. Referring to the continuing policy review in Washington, he repeated his belief that the only sufficient American policy in Iran would be to change the Iranian government and whipped the crowd into a standing ovation by pledging that in two years, Iran’s leaders would be gone and that “we here will celebrate in Tehran.”

The document that Bolton produced at Bannon’s request was not a strategy so much as a marketing plan for the administration to justify leaving the Iran deal. It did little to address what would happen on Day 2, after the United States pulled out of the deal. But Bolton’s views were hardly a secret to those who had spoken to him over the years or read the Op-Ed he wrote in The New York Times in 2015: Once American diplomacy had been set aside, Israel should bomb Iran.

Trump pulled out of the Iran deal in May 2018, just weeks after Bolton took over as his national security adviser, and now the president is navigating a slow-motion crisis. This June, attacks were launched against oil tankers in the Persian Gulf, and the United States pointed the finger at Tehran; in July, Britain impounded an Iranian tanker near Gibraltar, and Iran seized a British-flagged tanker in the gulf. American spy agencies warn of impending attacks by Iranian proxies on American troops in the region, and over the summer, Israel launched flurries of attacks on Iranian proxies in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon. The least surprising outcome of America’s withdrawal from the nuclear agreement with Iran, though, is that Iran now says that it, too, will no longer abide by the terms of the deal — a decision that could lead Tehran to once again stockpile highly enriched uranium, the fuel to build a nuclear bomb.

The president and his advisers have cited all these acts as evidence of Iran’s perfidy, but it was also a crisis foretold. A year before Trump pulled out of the deal, according to an American official, the Central Intelligence Agency circulated a classified assessment trying to predict how Iran would respond in the event that the Trump administration hardened its line. Its conclusion was simple: Radical elements of the government could be empowered and moderates sidelined, and Iran might try to exploit a diplomatic rupture to unleash an attack in the Persian Gulf, Iraq or elsewhere in the Middle East.

Ilan Goldenberg, a senior Pentagon official during the Obama administration, recalls the standoff in the years before the Iran nuclear deal as a kind of three-way bluff. Israel wanted the world to believe that it would strike Iran’s nuclear program (but hadn’t yet made up its mind). Iran wanted the world to believe it could get a nuclear weapon (but hadn’t yet made a decision to dash toward a bomb). The United States wanted the world to know it was ready to use military force to prevent Iran from getting a bomb (but in the end never had to show its hand). All three were taking steps to make the threats more credible, unsure when, or if, the other parties might blink.

Trump’s abrogation of the Iran deal has revived the poker game, but this time with an American president whose tendency to bluster about American power but avoid actually using it has made the situation in recent months even more volatile.

“President Trump cannot expect to be unpredictable and expect others to be predictable,” Javad Zarif, Iran’s foreign minister, said during a speech in Stockholm in August. “Unpredictability will lead to mutual unpredictability, and unpredictability is chaotic.”

Trump’s immediate goal appears to be to batter Iran’s economy with sanctions to the point that the country’s leaders will renegotiate the nuclear deal — and its military support for Hezbollah and other proxy groups — on terms that the administration deems more favorable to the United States. But it is also based on a gamble that Iran will break before November 2020, when the next American election could bring a new president who ends Trump’s hardball tactics.

This is all in aid of what the president’s advisers see as the larger goal, one embraced not only by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu of Israel but also by the Arab states in the Persian Gulf: a realignment of the Middle East, with Israel and select Sunni nations gaining supremacy over Iran and containing the world’s largest Shiite-majority state.

It is a wholly different vision than the one advanced by Obama, who committed to keeping Iran from getting a nuclear weapon but accepted the notion that Iran would become a counterweight to Saudi Arabia’s influence in the region. The two countries would have to “share the neighborhood,” as he put it, an idea that some Trump-administration officials sneer at. As one coolly explains, “We’ve decided to deal with Iran as it is, rather than as we’d like it to be.”

Those who were closest to Obama in the early days of his administration say he had a cleareyed transactional plan for bringing peace to the caldron of the Middle East. “We avoided an unnecessary and uncertain war, brought the Iranians to the table, gained time and space for negotiations and achieved an unprecedented and successful arms-control agreement,” says Tom Donilon, Obama’s national security adviser from 2010 to 2013. The deal, he said, “prevented Iran from obtaining a nuclear weapon and gave the international community unprecedented visibility into Iran’s activities,” all of which is in the “overwhelming interest of the United States.”

Trump’s withdrawal from the deal, compounded by the events of recent months, has revived fears not just that the United States could take military action against Iran or quietly bless an Israeli strike but also that all the parties could stumble into a conflict out of hubris, miscalculation or ignorance. A strike on Iran, however limited in its design, could unspool widespread chaos in the form of retaliation by Iranian proxy groups on American forces in the gulf region, escalating attacks on commercial ships that could send oil prices skyrocketing, waves of Hezbollah terrorist strikes against Israel, cyberattacks against the West and ultimately more American troops being sent to stamp out fires wherever Iran has influence — from Lebanon to Syria to Yemen to Iraq.

The story of how this simmering crisis began is in many ways a story about the complexities of America’s relationship with Israel, a story that has never been fully told. It is the story of a war narrowly averted, an arms agreement negotiated behind Israel’s back, two bedrock allies spying on each other and a battle over who will ultimately shape American foreign policy. Interviews with dozens of current and former American, Israeli and European officials over several months reveal the startling details of how close the Israeli military came to attacking Iran in 2012; the extent to which the Obama administration felt required to develop its own military contingency plans in the event of such an attack, including destroying a full-size mock-up of an Iranian nuclear facility in the western desert of the United States with a 30,000-pound bomb; how Americans monitored Israel even as Israel monitored Iran, with American satellites capturing images of Israel launching surveillance drones into Iran from a base in Azerbaijan; and previously unknown details about the scope of Netanyahu’s pressure campaign to get Trump to leave the Iran deal.

Netanyahu recently eclipsed David Ben-Gurion as Israel’s longest-serving prime minister, but once again he is fighting for political survival, with another vote to determine his future as prime minister set for Sept. 17. In a wrinkle of history, some of his opponents are the same people who vigorously opposed his push to strike Iran several years ago.

Regardless of the outcome of the election, the landscape of the current Iran crisis could change quickly, and Trump even said during the recent Group of 7 summit that he might meet in the coming weeks with President Hassan Rouhani of Iran. That prospect has set off alarms in Israel, where some officials raise fears in private that the American president in whom they had invested so much hope has gone wobbly. But Netanyahu, at least publicly, says he isn’t worried. In an interview in August in his office in Jerusalem, he acknowledged the possibility that Trump, like Obama before him, might try to avoid a war and instead attempt to reach a settlement over Iran’s nuclear program.

“But this time,” Netanyahu said, “we will have far greater ability to exert influence.”

2. ‘Total Mutual Striptease’

The first public revelation about a clandestine uranium-enrichment program in Iran came in the summer of 2002, as America was preparing for war with Iraq. Western intelligence services had found that scientists at a nuclear facility near Natanz, in north-central Iran, had begun an effort to enrich uranium ore. A dossier of these findings leaked to a group affiliated with the M.E.K., which went public with the information at a news conference in Washington. The Bush administration, preoccupied with Iraq, chose to pursue a path of negotiation with Iran, coupled with sanctions. For many Israeli officials, the revelation reinforced a conclusion that they had already drawn: The United States was making war on the wrong country.

The Israeli leadership grew even more concerned in 2005, when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was elected president of Iran. Ahmadinejad immediately made known his views about Israel, unleashing fiery rhetoric calling for the end to the nation and calling the Nazi extermination of Jews a myth. He increased support for militant groups like Hamas and Hezbollah — and, American and Israeli analysts agreed, he also began to accelerate the nation’s nuclear program. In a nation built by survivors of the Holocaust, the moves confirmed for many that Iran presented an existential threat.

Israel’s leadership at that time was going through an uncertain moment. In January 2006, Ariel Sharon, Israel’s prime minister, suffered a stroke that left him in a vegetative state. A deputy, Ehud Olmert, stepping up to replace him, gave a free hand and endless resources to the clandestine campaign that the Mossad, Israel’s civilian intelligence agency, was running to stop, or at least delay, the Iranian nuclear project. In 2007, Ehud Barak, a former prime minister, became Olmert’s defense minister and issued a written order to the Israeli military’s general staff to develop plans for a large-scale attack on Iran. But Olmert thought that many were exaggerating the immediacy of the Iran threat. His own position, he recalls now, “was that it was not Israel that should lead a military operation, even with the knowledge that Iran might indeed succeed in getting a bomb. Just as Pakistan had the bomb and nothing happened, Israel could also accept and survive Iran having the bomb.”

Netanyahu, then in the leadership of the conservative Likud party, took a starkly different position. He had gone to high school and college in the United States, earning a business degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and working at the Boston Consulting Group, where he became friends with the future Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney. During his first term as prime minister — from 1996 to 1999 — he warned a joint session of Congress that only the United States could prevent the “catastrophic consequences” of a nuclear-armed Iran.

Now the Likud leader was once again enlisting Israel’s closest ally into what Uzi Arad, one of his former top advisers, describes as “a personal crusade against the Iranian threat.” Speaking at the annual conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or Aipac, in Washington in 2007, Netanyahu demanded more sanctions on Iran. He also met with Dick Cheney, then the vice president, and, according to Arad, warned that if the West failed to present a credible threat of military action, Iran would surely get the bomb.

In Cheney, Netanyahu had found the right audience. The Pentagon’s military and civilian leadership had little appetite for another war of pre-emption, and by then neither did the president. But Cheney, like Bolton, had long taken a more expansive view, and he continued to argue for military action against Iran well into George W. Bush’s second term.

During a meeting with Bush in May 2008, the vice president sparred with Robert Gates, the defense secretary, over the wisdom of a strike against Iran. Gates argued that a military move against Iran by the United States or Israel would strengthen radical factions in the Iranian government and rally the country behind the Iranian regime. Gates said that Olmert should be told in the most direct terms that Israel should not launch a unilateral attack. Cheney disagreed on every point, saying that a strike on Iran was necessary and that at minimum the White House should enable Israel to act. Gates recalled Cheney’s thinking in his memoir: Twenty years on, “if there was a nuclear-armed Iran, people would say the Bush administration could have stopped it.”

That same month, Bush arrived in Jerusalem for his last visit to Israel as president. Olmert hoped to get American and Israeli spies to share more intelligence about Iran, and he used a private meeting at his residence to make his case. When the aides had cleared the room, according to an official who was familiar with the conversation, Olmert moved in to seal the deal. “Come, let’s open the books and be transparent with each other,” he said. Bush agreed, a decision that led to far greater intelligence cooperation between American and Israeli spy services — a “total mutual striptease” in the words of one of Olmert’s former aides. This cooperation would culminate in the Olympic Games operation, which deployed sophisticated computer malware, including the Stuxnet virus, to sabotage Iranian nuclear facilities. This was one path forward to containing Iran.

But Bush was also made keenly aware of the other path. One night during his visit, Olmert invited him for a dinner at his residence with the members of his national security cabinet, including Barak, the defense minister, who like Cheney had taken an increasingly hawkish position on Iran during internal discussions. As Olmert tells the story, he and Bush walked alone into a side lounge after the dinner. As the two men relaxed in leather armchairs, Olmert smoking a cigar, the prime minister told Bush that Barak was waiting and wanted an audience.

Bush was reluctant, according to Olmert. “I understand that it is politically important for you to let him in,” Olmert recalls Bush explaining, “but you know my position on the Iran issue. I am unequivocally against an attack.”

Olmert persisted. Bush eventually relented, and soon Barak was in the room, smoking a cigar and sipping a whiskey. He delivered a comprehensive lecture about the Iran threat. Finally, Bush cut him off. “He banged on the table like this,” Olmert recalls, “and he said: ‘General Barak, do you know what no means? No is no.”’

Barak, for his part, remembers much about the affair differently, including Bush’s reaction. In Barak’s version, when he finished making his case to the American president, Bush turned to Olmert but pointed a finger directly at Barak. “This guy scares the living shit out of me,” Barak recalls him saying. (A spokesman for Bush says the former president does not recall either of these conversations.)

Looking back at that meeting, Barak now sees Bush’s position as somewhat irrelevant. “The truth is that Bush’s warning did not really make any difference for us,” he says, “because as of the end of 2008, we did not have a real, feasible plan for attacking Iran.”

Barak was already looking toward the future. “We knew that anything that happened after that would, in any case, be under a different president.”

3. ‘Obama Is Part of the Problem’

Netanyahu began his second term as Israel’s prime minister just months after Obama took office in 2009. Despite their ideological differences, Netanyahu had some cause to believe that the new American president might be a more willing partner in his effort against Iran. Though Obama first gained attention for his opposition to the Iraq war, he frequently raised the Iran threat during the campaign and told an Aipac audience in June 2008 that he would “always keep the threat of military action on the table to defend our security and our ally Israel.”

During their first meeting in the White House in May 2009, anxious aides waited outside the Oval Office as the two leaders met alone. It was an interminable meeting, and some may have figured that the savvy, experienced Israeli prime minister was lecturing the young American president about the Palestinians and the hard truths of Israeli security.

But when the door opened, it was Netanyahu who appeared shell-shocked, Arad recalls: “Bibi did not say anything, but he looked ashen.” It was hours later when he told aides that Obama had attacked him and implored him — actually demanded him, in Netanyahu’s view — to freeze Israel’s settlements in the West Bank right away, with “not a single brick” added in the future, according to an Israeli official with direct knowledge of the meeting. “Bibi left that place traumatized,” Arad says. Speaking now, Netanyahu says that “Obama came from another direction, one that adopted most of the Palestinian narrative,” and ruefully cites the “not a single brick” line to argue that the American president was against him from the very beginning. (A former Obama-administration official with knowledge of the White House meeting says that Obama did not in fact use that phrase.)

The relationship between the two governments was warmer at the cabinet level. Netanyahu had brought in Arad to be his national security adviser, and Arad established a direct link with Obama’s own national security advisers — Gen. James L. Jones and then Donilon — to discuss the Iranian nuclear program.

American and Israeli officials met regularly in person and even more frequently over encrypted video conferences. The Obama administration insisted on total secrecy about the meetings, and an urgent issue was already on the agenda: the continuing construction of a secret nuclear facility, buried deep inside a mountain, not far from Iran’s holy city of Qum.

The Fordow fuel enrichment plant was discovered in April 2008 by a source working for British intelligence, which in turn passed rudimentary details about the plant to American and Israeli spy agencies. Unlike the Natanz plant, Fordow was too small to produce usable amounts of civilian nuclear fuel, making it likely that it was created solely for the drive toward a nuclear weapon.

American and Israeli officials were now faced with the fact that ongoing covert operations to sabotage Iran’s nuclear effort had failed to halt the program. The Israeli perspective, as advanced by Barak, was relatively simple: The world was running out of time before Iran entered what Barak called the “zone of immunity,” the point at which the nuclear program was so advanced and so well defended that any strike would have too little impact to be worth the risk. The United States, with its bunker-buster bombs that could penetrate deep into underground facilities, could wait to strike. But, Barak argued, Israel had no such luxury. If it was going to act alone, it would need to do it sooner. Some American military planners derided Barak’s tactic as “mowing the grass” — a small-bore effort that would need to be repeated again and again — but it might have been more like a way to get the United States to move first. “Barak would tell us, ‘We can’t do what you do, so we need to do it sooner,’ ” says Dennis Ross, who handled Iran policy at the National Security Council during Obama’s first term. “We interpreted that as designed to put pressure on us.”

A parade of top American officials began flying to Israel during Obama’s first term to take the measure of the Israeli planning and to convince Netanyahu and Barak that the United States was taking the problem seriously and that Iran was hardly on the brink of getting the bomb. “Our message was that we understand your concerns, and please don’t go off on a hair trigger and start a war, because you’re going to want us to come in behind you,” says Wendy Sherman, a top State Department official in Obama’s administration.

One of the first to make the trip was Robert Gates, whom Obama had asked to stay on at the Pentagon. He arrived in Israel in July 2009, just weeks after the Green Revolution brought thousands of protesters into the streets of Tehran. The Iranian government seemed fragile, and Netanyahu told Gates he was convinced that a military strike on Iran would do more than set back its nuclear program; it could instigate the overthrow of a regime loathed by the Iranian people. Besides, Netanyahu said, as Gates recalls in his memoir, the Iranian response to the attack would be limited. Gates pushed back, just as he had a year earlier against Cheney.

He said Netanyahu was misled by history. Perhaps Iraq did not retaliate after Israel bombed the Osirak nuclear reactor in 1981, just as Syria did nothing when Israel bombed a suspected Syrian nuclear reactor in 2007. But Iran was very different from Iraq and Syria, he said. His meaning was clear: Iran was a powerful country with a capable military and proxy groups like Hezbollah that could unleash serious violence from just over Israel’s borders.

The relationship between Obama and Netanyahu continued to fracture. Michael Oren, the Israeli ambassador in Washington at the time, recalls that Netanyahu began to say that “Obama is part of the problem, not the solution.” The uncomfortable relationship was apparent to all sides. Arad recalls that when he accompanied Netanyahu to Washington in 2010 for another meeting with Obama, Vice President Joe Biden threw his arm around Arad and said with a smile, “Just remember that I am your best fucking friend here.”

4. ‘A Highly Complicated Affair’

Obama took the possibility of a sudden Israeli strike seriously. American spy satellites watched Israeli drones take off from bases in Azerbaijan and fly south over the Iranian border — taking extensive pictures of Iran’s nuclear sites and probing whether Iranian air defenses spotted the intrusion. American military leaders made guesses about whether the Israelis might choose a time of the month when the light was higher or lower, or a time of the year when sandstorms occur more or less regularly. Military planners ran war games to forecast how Tehran might respond to an Israeli strike and how America should respond in return:

Would Iran assume that any attack had been blessed by the United States and hit American military forces in the Middle East? The results were dismal: The Israeli strikes dealt only minor setbacks to Iran’s nuclear program, and the United States was enmeshed in yet another war in the Middle East.

The White House eventually made the decision that the United States would not join a pre-emptive strike. If Israel launched such a strike, the Pentagon wouldn’t assist in the operation, but it wouldn’t stand in Israel’s way. At the same time, Obama was quietly ordering a buildup of America’s arsenal around the Persian Gulf. If Israel was going to trigger a war, the thinking went, it was better to have forces in the region beforehand rather than rush them there after the fact, when Iran would surely interpret the deployments as a surge to support Israel. Aircraft-carrier strike groups and destroyers with Aegis ballistic-missile defense systems moved through the Strait of Hormuz; F-22 jets arrived in the United Arab Emirates, and Patriot missile batteries were sent to the United Arab Emirates and other gulf allies. Some of the deployments were announced as routine moves to support the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. “We didn’t want the Israelis to mistake it for a green light,” one Obama-administration official says.

What they didn’t know was, at least at that time, whether Netanyahu had the ability — or even the real will — to pull off a strike.

It was a complicated question, and one that was the subject of considerable debate even at the highest levels of the Israeli government. In November 2010, Netanyahu and Barak convened a private meeting at Mossad headquarters to discuss a recently devised Iran attack plan with the chiefs of Israel’s defense establishment.

According to Barak, the conversation quickly became contentious when Lt. Gen. Gabi Ashkenazi, the military chief of staff, told the room that despite major advancements, the Israel Defense Forces had not yet crossed the threshold of “operational capability.”

Ashkenazi’s statement punctured the optimism that had been building around a strike. “The moment he says there’s no operational capability, then you have no choice,” Barak recalls now. “Hypothetically, you can fire him if you want to, but you can’t say, ‘Let’s go.’ ”

Another influential official spoke up: Meir Dagan, the longtime head of the Mossad, who had been directing Israel’s secret war on Iran. His credentials as an Iran hawk were hardly in dispute, and he was coming to the end of a national security career that began in the mid-1960s, so he had plenty of political capital to burn. He told Netanyahu and Barak that a military campaign would be foolish and could undo all the progress the covert campaign had made. Dagan saw the proposed campaign as a scheme by two cynical politicians seeking the widespread public support that an attack would give them in the next election.

Yuval Diskin, the head of Shin Bet, Israel’s domestic intelligence service, was also against an attack. Barak and Netanyahu may not have been interested in the guidance of their advisers, but they did “not have the authority,” Diskin told them, to go to war without government approval. Netanyahu had to back down.

The Israeli prime minister became increasingly suspicious of his senior advisers. He now accuses Dagan of leaking the attack plan to the C.I.A., “intending to disrupt it,” a betrayal that to Netanyahu’s mind was “absolutely inconceivable.” Within a year, Dagan, Ashkenazi and Diskin, along with Uzi Arad, were no longer in their posts.

If Netanyahu hoped his handpicked replacements would be more compliant, however, he would soon be disappointed. Many others in the government, including Benny Gantz, the chief of staff who succeeded Ashkenazi, were also against the attack, according to three officials who were part of the decision-making process at that time. For Gantz, who is now running against Netanyahu for the job of prime minister, it was a practical matter. “Even those who have not seen the intelligence understand that it would be a highly complicated affair and — if the impact it would have on other countries is taken into account — a strategic affair of the highest level,” he says.

5. ‘We Were Running Out of Time’

Netanyahu’s relentless pressure on Obama may have had an unintended consequence. The American president, with limited information about what the Israelis might do, increased his urgent pursuit of a major new initiative: a clandestine negotiation with Iran.

For Obama, the J.C.P.O.A. would be the centerpiece of his foreign-policy legacy; it was not just a deal but a framework for regional stability — a way to shut the Pandora’s box his predecessor blew open in 2003. For Netanyahu, though, it would be the ultimate betrayal — Israel’s closest ally negotiating behind its back with its most bitter enemy.

The effort began in late 2010, with Dennis Ross and Puneet Talwar, two of Obama’s top national security advisers, aboard a commercial aircraft bound for Muscat, Oman. The country’s ruler, Sultan Qaboos bin Said, was helping mediate the sensitive negotiations around the release of several American backpackers who had been detained in Iran under suspicion of being spies. Now Oman would help the United States open a back channel for far more ambitious discussions.

Inside one of the sultan’s palaces, Ross and Talwar delivered a message that Obama wanted the Omani ruler to give to only Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei: The United States thought there was a chance for a peaceful denouement to the nuclear standoff with Iran but was prepared to take military action if Iran rejected diplomacy. The United States could accept Iran’s harnessing nuclear power for civilian use, but any military purpose for its nuclear program was intolerable.

Obama had long believed that there might be a sliver of hope for a nuclear deal, and the White House had already begun a campaign of punishing economic sanctions designed to pressure Tehran into negotiations. But some former administration officials said the prospect of an Israeli military operation gave energy to the diplomatic push. “Did the Israeli pressure affect our decision to begin talks?” Ross says. “Without a doubt. Unless we could do something that changed the equation, the Israelis were going to act militarily.” Ilan Goldenberg, the former Pentagon official handling Iran issues, says, “We felt we were running out of time.”

Others within the administration disagreed that Israeli pressure played a significant role in the effort. “President Obama’s push for a diplomatic resolution to the Iranian nuclear challenge long predated Prime Minister Netanyahu’s saber-rattling,” says Ned Price, who served as a spokesman for Obama’s National Security Council. “In fact, it even predated his current stint as prime minister.

Candidate Obama pledged in 2007 to seek the very type of diplomatic achievement he, together with many of our closest allies and partners, struck as president in 2015.”

Obama decided to keep the Israelis — and, for that matter, every other American ally — in the dark about the secret discussions. Some in his administration feared that if Obama told Netanyahu about the nascent talks, the Israelis would leak word of them to tank any future deal. “It was too big a risk,” one former senior Obama-administration official said. “The trust between the two leaders was badly frayed by this point. That introduced an element of uncertainty about what Bibi or people around him would do if they had the information.”

The secrecy around the talks remains a freighted subject among many former Obama officials, one that few are willing to discuss on the record. Some believed that the Obama-Netanyahu relationship had grown so toxic that the Israeli prime minister couldn’t be trusted. And, they argue, the strategy worked: Talks stayed quiet long enough for them to mature into serious negotiations and, ultimately, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action. Others say it was needlessly provocative, sowing further distrust in an already dismal relationship and creating the appearance that the Obama White House wasn’t confident enough in its strategy to defend it to the Israelis. “That was an ongoing debate,” says Wendy Sherman, who was closely involved in the negotiations. “I was on the side of telling them sooner rather than later. It was a very hard call.”

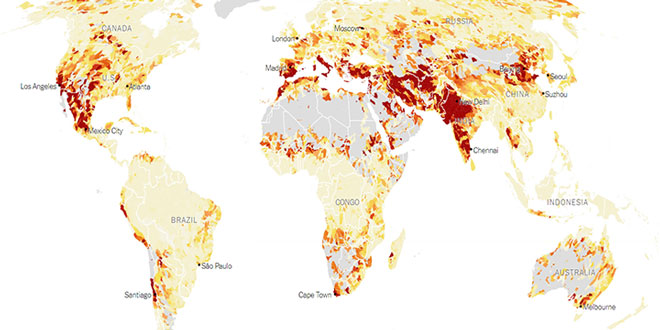

A Quarter of Humanity Faces Looming Water Crises

By Somini Sengupta and Weiyi CaiAug. 6, 2019

BANGALORE, India — Countries that are home to one-fourth of Earth’s population face an increasingly urgent risk: The prospect of running out of water.

From India to Iran to Botswana, 17 countries around the world are currently under extremely high water stress, meaning they are using almost all the water they have, according to new World Resources Institute data published Tuesday.

Many are arid countries to begin with; some are squandering what water they have. Several are relying too heavily on groundwater, which instead they should be replenishing and saving for times of drought.

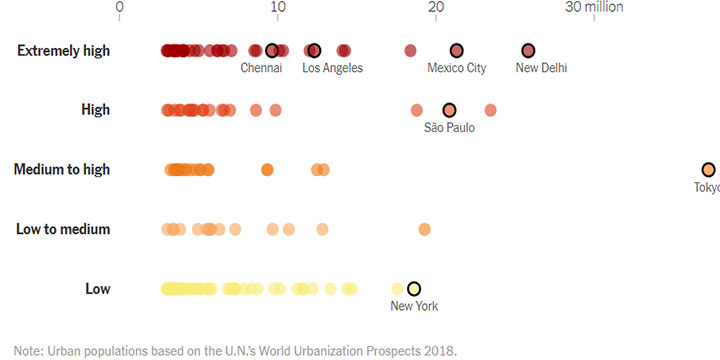

In those countries are several big, thirsty cities that have faced acute shortages recently, including São Paulo, Brazil; Chennai, India; and Cape Town, which in 2018 narrowly beat what it called Day Zero — the day when all its dams would be dry.

Water Stress Levels of Urban Areas with Population Bigger than 3 Million

More than a third of major urban areas with more than 3 million people are under high or extremely high water stress.

“We’re likely to see more of these Day Zeros in the future,” said Betsy Otto, who directs the global water program at the World Resources Institute. “The picture is alarming in many places around the world.”

Climate change heightens the risk. As rainfall becomes more erratic, the water supply becomes less reliable. At the same time, as the days grow hotter, more water evaporates from reservoirs just as demand for water increases.

Water-stressed places are sometimes cursed by two extremes. São Paulo was ravaged by floods a year after its taps nearly ran dry. Chennai suffered fatal floods four years ago, and now its reservoirs are almost empty.

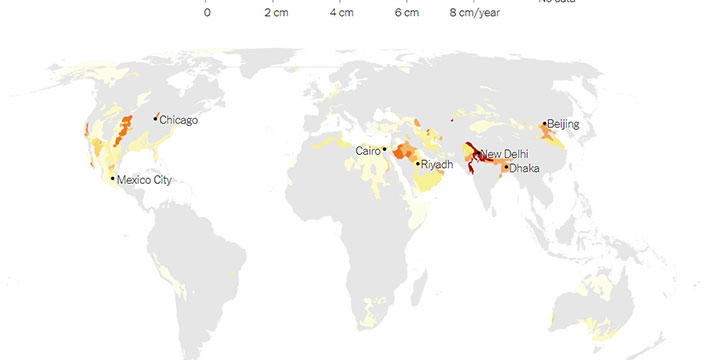

Groundwater is going fast

Mexico’s capital, Mexico City, is drawing groundwater so fast that the city is literally sinking. Dhaka, Bangladesh, relies so heavily on its groundwater for both its residents and its water-guzzling garment factories that it now draws water from aquifers hundreds of feet deep. Chennai’s thirsty residents, accustomed to relying on groundwater for years, are now finding there’s none left. Across India and Pakistan, farmers are draining aquifers to grow water-intensive crops like cotton and rice.

More stress in the forecast

Today, among cities with more than 3 million people, World Resources Institute researchers concluded that 33 of them, with a combined population of over 255 million, face extremely high water stress, with repercussions for public health and social unrest.

By 2030, the number of cities in the extremely high stress category is expected to rise to 45 and include nearly 470 million people.

World Water Stress Projection

Extremely high High Medium to high Low to medium Low No data

How to fix the problem?

The stakes are high for water-stressed places. When a city or a country is using nearly all the water available, a bad drought can be catastrophic.

After a three-year drought, Cape Town in 2018 was forced to take extraordinary measures to ration what little it had left in its reservoirs. That acute crisis only magnified a chronic challenge. Cape Town’s 4 million residents are competing with farmers for limited water resources.

Likewise, Los Angeles. Its most recent drought ended this year. But its water supply isn’t keeping pace with its galloping demand and its penchant for private backyard swimming pools doesn’t help.

For Bangalore, a couple of years of paltry rains revealed how badly the city has managed its water. The many lakes that once dotted the city and its surrounding areas have either been built-over or filled with the city’s waste. They can no longer be the rainwater storage tanks they once were. And so the city must venture further and further away to draw water for its 8.4 million residents, and much of it is wasted along the way.

A lot can be done to improve water management, though.

First, city officials can plug leaks in the water distribution system. Wastewater can be recycled. Rain can be harvested and saved for lean times: lakes and wetlands can be cleaned up and old wells can be restored. And, farmers can switch from water-intensive crops, like rice, and instead grow less-thirsty crops like millet.

“Water is a local problem and it needs local solutions,” said Priyanka Jamwal, a fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment in Bangalore.

US spies say Trump’s G7 performance suggests he’s either a ‘Russian asset’ or a ‘useful idiot’ for Putin

Current and former spies are floored by President Donald Trump’sfervent defense of Russia at this year’s G7 summit in Biarritz, France.

“It’s hard to see the bar anymore since it’s been pushed so far down the last few years, but President Trump’s behavior over the weekend was a new low,” one FBI agent who works in counterintelligence told Insider.

At the summit, Trump aggressively lobbied for Russia to be readmitted into the G7, refused to hold it accountable for violating international law, blamed former President Barack Obama for Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and expressed sympathy for Russian President Vladimir Putin.

One former senior Justice Department official, who worked closely with the former special counsel Robert Mueller when he was the FBI director, told Insider Trump’s behavior was “directly out of the Putin playbook. We have a Russian asset sitting in the Oval Office.”

A former CIA operative told Insider the evidence is “overwhelming” that Trump is a Russian agent, but another CIA and NSA veteran said it was more likely Trump was currying favor with Putin for future business deals.

Meanwhile, a recently retired FBI special agent told Insider that Trump’s freewheeling and often unfounded statements make it more likely that he’s a “useful idiot” for the Russians. But “it would not surprise me in the least if the Russians had at least one asset in Trump’s inner circle.”

“It’s hard to see the bar anymore since it’s been pushed so far down the last few years, but President Trump’s behavior over the weekend was a new low.”

That was the assessment an FBI agent who works in counterintelligence gave Insider of President Donald Trump’s performance at this year’s G7 summit in Biarritz, France. The agent requested anonymity because they feared that speaking publicly on the matter would jeopardize their job.

Trump’s attendance at the G7 summit was peppered with controversy, but none was more notable than his fervent defense of Russia’s military and cyber aggression around the world, and its violation of international law in Ukraine.

Trump repeatedly refused to hold Russia accountable for annexing Crimea in 2014, blamed former President Barack Obama for Russia’s move to annex it, expressed sympathy for Russian President Vladimir Putin, and castigated other G7 members for not giving the country a seat at the table.

Since being booted from the G8 after annexing Crimea, Russia’s done little to make up for its actions. In fact, by many accounts, it’s stepped up its aggression.

In addition to continuing to encroach on Ukraine, the Russian government interfered in the 2016 US election and was behind the attempted assassination of a former Russian spy in the UK. US officials also warn that as the 2020 election looms, the Russians are stepping up their cyberactivities against the US and have repeatedly tried to attack US power grids.

“What in God’s name made Trump think it would be a good idea to ask to bring Russia back to the table?” the FBI agent told Insider. “How does this serve US national-security interests?”

Trump’s advocacy for Russia is renewing concerns among intelligence veterans that Trump may be a Russian “asset” who can be manipulated or influenced to serve Russian interests, although some also speculate that Trump could just be currying favor for future business deals.

A former senior Justice Department official, who worked closely with the former special counsel Robert Mueller when he was FBI director, didn’t mince words when reacting to Trump’s performance at the G7 summit: “We have a Russian asset sitting in the Oval Office.”

“There is no fathomable explanation for why the president said these things,” the former official said. “Letting Russia off the hook for bullying smaller countries and then blaming Obama for it? It’s directly out of the Putin playbook.”

While arguing for Russia to be invited back into the G7, Trump said the country would be helpful in addressing hot-button issues like Iran, Syria, and North Korea and that the alliance was better off with Russia “inside rather than outside.”

But Russia is a staunch ally of Syria’s Assad regime, and it’s also cozied up to Iran in recent years. US military and intelligence officials view Russia as one of the US’s foremost rivals and believe it generally stands in opposition to American interests.

Glenn Carle, a former CIA covert operative and frequent Trump critic, told Insider there’s been “no question” in his mind for years that the president is behaving like “a spy for the Russians.”

“The evidence is so overwhelming that in my 35 years in intelligence, I have never seen anything so certain,” Carle said, adding that he’s spoken with several intelligence veterans about the matter in the four years since Trump first launched his presidential campaign, many of whom believe Trump’s actions are a threat to national security.

Read more: Russia came out the winner of this year’s G7 summit despite being kicked out, and Trump looked like ‘Putin’s puppet’

“Intelligence assets become convinced to be spies for multiple reasons,” Carle, who specialized in getting foreign spies to become turncoats when he was at the CIA, said in an earlier interview with Insider. “It might start with kompromat or financial hooks, and the asset may be convinced he is acting as a patriot until he becomes accustomed to his role.”

“Trump clearly responds favorably to praise,” he said. “And over the years, the handling officer — Putin, in this case — realizes what the asset wants, and that’s what they provide. Trump wants to be told he’s the greatest, so that’s what you tell him, over and over again, until he comes to believe that is the motivation for his actions.”

Frank Montoya Jr., a recently retired FBI special agent, told Insider it’s “hard not to think the Russians have an asset in the White House.”

But he added that Trump’s freewheeling and often false statements imply he’s “not playing with a full deck on any matter of state these days. Still, those same delusions are what give me pause when conclusions are reached about the likelihood he is a Russian asset.”

“Useful idiot is more like it,” Montoya said. But he added that given the abundance of meetings and contacts between Trump associates and Russians before, during, and after the election, “it would not surprise me in the least if the Russians had at least one asset in Trump’s inner circle.”

Robert Deitz, a former top lawyer at the CIA and the National Security Agency, agreed that Trump was catering to Putin’s interests, but he disagreed on why.

“I think what’s going on right now is an Occam’s razor scenario,” he told Insider, referring to the philosophical theory that the simplest explanation for an event is often the correct one.

“Trump wants to do deals with Russia when he leaves the presidency,” Deitz said. “We already know he was interested in building a Trump Tower in Moscow before and during the election. The best way of doing a deal with Putin is to be nice to him, so I think what Trump is doing is currying favor.”

He emphasized, however, that regardless of Trump’s motives for being subservient to Putin, “it’s still harmful” to US interests.

“When Trump goes to bed each night, what do you think his last thoughts are: the welfare of the United States, or the size of his bank account?” Deitz added.

Trump’s defense of Putin at the G7 summit didn’t go unnoticed in Russia.

According to The Washington Post, one show on the state-run Rossiya-1 network played a celebratory soundtrack as it showed six video clips of Trump demanding that Putin be given a seat at the table.

The Russian media analyst Julia Davis said that Kremlin-controlled media reacted to Trump’s G7 performance with laughter and mockery.

One anchor rejoiced that “Trump is dancing to Putin’s tune,” while others were amused by the “maniacal persistence” with which Trump was lobbying for Russia.

This isn’t the first time the president has been accused of working to advance Russia’s interests ahead of the US’s.

Perhaps the sharpest example of this was when Trump and Putin held a bilateral summit in Helsinki last year. After the meeting, Trump stunned the US national-security apparatus and foreign allies when he sided with Russia over the US intelligence community, blamed “both sides” for the deterioration of US-Russia relations, and praised Putin as being “extremely strong and powerful.”

In 2017, Trump refused to accept the US intelligence-community finding that Moscow meddled in the 2016 race to propel Trump to the presidency.

That May, he fired FBI director James Comey, who was overseeing the FBI’s investigation into Russia’s election interference and cited “this Russia thing” as the reason. Two days after firing Comey, Trump shared classified intelligence with two Russian officials in the Oval Office and told them firing Comey had taken “great pressure” off of him.

Shortly after, the FBI began investigating whether Trump was a Russian agent.

The UAE’s ambitions backfire as it finds itself on the front line of U.S.-Iran tensions

By Liz Sly August 11 at 7:12 PM

ABU DHABI, United Arab Emirates — One of America’s staunchest allies in the Middle East and a driving force behind President Trump’s hard-line approach to Iran is breaking ranks with Washington, calling into question how reliable an ally it would be in the event of a war between the United States and Iran.

In the weeks since the United States dispatched naval reinforcements to the Persian Gulf to deter Iranian threats to shipping, the government of the United Arab Emirates has sent a coast guard delegation to Tehran to discuss maritime security, putting it at odds with Washington’s goal of isolating Iran. After limpet mines exploded on tankers off the UAE’s coast in June, the UAE stood apart from the United States and Saudi Arabia and declined to blame Iran.

It also announced a drawdown of troops from Yemen, where, alongside Saudi Arabia, it has been battling Iranian-backed Houthis for control of the country. That opened the door this past weekend to a takeover by UAE-backed separatist militias of the U.S.-supported government in the city of Aden, a further divergence from U.S. policy.

Former U.S. defense secretary Jim Mattis once nicknamed the UAE “Little Sparta” because of its stalwart support for U.S. military ventures around the world, including in Somalia and Afghanistan. Much of the recent war against the Islamic State was launched from the U.S. air base located at al-Dhafra in the UAE, an integral part of America’s security footprint in the Middle East.

But as its relationship with Washington puts the UAE on the front line of a potential war, the Emiratis are shifting gears, calling for de-escalation with Iran and distancing themselves from the Trump administration’s bellicose rhetoric.

“The UAE does not want war. The most important thing is security and stability and bringing peace to this part of the world,” said an Emirati official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive foreign policy issues.

Whether the United States could count on Emirati support should the current tensions lead to war with Iran may now be in doubt, diplomats and analysts say.

“The UAE is increasingly tilting away from U.S. objectives,” said Theodore Karasik of the Washington-based Gulf State Analytics. “Is it the weak link in the Trump policy of maximum pressure? It may be.”

This is not the first time UAE policies have diverged from those of Washington. The small but fabulously wealthy country has over the past decade steadily expanded its reach across the Middle East in pursuit of an agenda driven largely by the staunch opposition of its powerful crown prince, Mohammed bin Zayed, to all forms of political Islam.

The UAE sponsored the 2013 coup in Egypt that overthrew country’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, whose Muslim Brotherhood government was supported by the United States. It has backed the renegade warlord Khalifa Hifter against the U.S.- and U.N.-backed government in Libya, which is aligned with Islamist militias. It spearheaded a blockade alongside Saudi Arabia against Qatar, an ally of the United States that has promoted Islamist movements in the region.

Abu Dhabi has also embarked on an influence campaign in Washington that has given the UAE a potent voice in the White House, helping shape Middle East policy at the highest levels. The UAE was a vocal critic of the 2015 nuclear pact signed by the United States and other world powers with Iran, and it supported Trump’s decision to walk away from the deal last year.

The UAE never intended the U.S. withdrawal from the deal to lead to confrontations such as those that have taken place in the Persian Gulf, Emirati officials say. Rather, they say, the UAE continues to hope, in line with Washington’s declared policy, that the tough sanctions imposed on Iran by the Trump administration will bring Iran back to the negotiating table.

Instead, Iran has pushed back, embarking on a campaign of threats and harassment against shipping in the Persian Gulf that has drawn U.S. and British naval reinforcements to the area — and appears to have caught the UAE off guard.

The UAE’s location, economy and reputation as a safe haven for foreigners make it uniquely susceptible to the fallout from even a low-level confrontation, perhaps more than any other country in the region, analysts say. The Strait of Hormuz, where war is most likely to break out, envelops the Emirati coastline and the UAE depends on the waterway for the trade on which its economy has soared.

To build the skyscrapers and service the hotels that have attracted tourists and business executives less welcome in many other parts of the Middle East, the country has recruited foreigners from around the world. Expatriates account for about 90 percent of the UAE’s population, and they sustain almost all of its vital infrastructure, including hospitals and the armed forces.

The entire country could be brought to a halt if foreigners were to become frightened and leave, said Elizabeth Dickinson of the International Crisis Group.

“The stakes for the UAE are stupendously high. An attack that hit Emirati soil or damaged their critical infrastructure would be devastating,” she said. “It would symbolically compromise the reputation of one of the region’s most economically dynamic countries.”

That the UAE would be considered a target should war break out was underscored by Hasan Nasrallah, the leader of the Lebanese Shiite Hezbollah militia and Iran’s closest regional ally, in an interview in July. “What will be left of the UAE’s glass towers if a war breaks out?” he asked, in a barely veiled threat. “If the UAE was destroyed . . . would that be in the interests of the Emirati rulers and people?”

Emirati officials dispute that they are switching course and say they intend to remain engaged in the wider region.

The troop drawdown in Yemen had been signaled by senior officials for months, they say, and came about because peace talks sponsored by the United Nations are underway, a goal of the military intervention.

The UAE delegation’s visit to Tehran came in the context of negotiations over fishing rights in the Strait of Hormuz and was not linked to the current crisis, they add. The appeals for de-escalation don’t change the Emiratis’ position on Iran: that its regional expansionism is dangerous and its program to develop an advanced ballistic-missile capability must be curtailed, according to the officials.

But there have been whispered recriminations among Emiratis that the UAE has overreached, that the regional ambitions of Mohammed bin Zayed, the de facto leader, have strayed too far from the country’s vision of itself as a beacon of prosperity and stability, according to residents and diplomats.

“It looks like it was overreach, and they didn’t calculate the consequences,” said a Dubai businessman, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the UAE’s authoritarian system of government prescribes harsh punishments for those who criticize the leadership.

“Their military expansion destroyed the idea of the UAE being a safe haven, and now they’re feeling the danger of going along with the Americans.”

The UAE’s support for Trump’s retreat from the Iran deal is only the latest in a string of ventures that haven’t worked out quite as the Emiratis intended.

The Yemen war bogged down, dragged on and drew international criticism for the high civilian death toll, even though it was Saudi Arabia that carried out most of the airstrikes that caused the casualties. The two-year-old blockade of Qatar has failed to isolate Qatar from the international community but helped drag down the UAE’s economy. The UAE’s military support for the Libyan warlord Hifter contributed to his stalled offensive on the capital, Tripoli, that has caused bloodshed but no shift in the balance of power in Libya.

In Washington, an apparent attempt by the crown prince to forge ties between Russia and the Trump administration backfired, drawing the UAE into Robert S. Mueller III’s investigation into Russian attempts to influence the 2016 U.S. election. Mohammed is the only foreign leader aside from Russian President Vladimir Putin to feature in the report, mostly in connection with a 2017 meeting he arranged at his Four Seasons hotel in the Seychelles between Trump associate Erik Prince and Russian financier Kirill Dmitriev.

Investigations into the actions of some of the crown prince’s associates are continuing, including those of Republican fundraiser Thomas J. Barrack Jr., who last week was accused by congressional Democrats of seeking to influence a Trump campaign speech by running parts of it by Emirati officials.

If the UAE made any mistake, it was to align itself too closely with Trump, who has proved highly unpredictable, said Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, an Emirati political scientist who is based in Dubai. The Emirates welcomed Trump as an alternative to President Barack Obama, whose pursuit of a nuclear deal with Iran ignored the concerns of the UAE. Trump has proved an equally unreliable ally, he said.

“Do you really want to have all your eggs in Trump’s basket?” he said. When Trump threatened in June to retaliate against Iran for shooting down an American drone and then changed his mind, “it was a big moment for the UAE and for the region, too. Everyone assumed Trump is someone who carries through with his word, and when the moment came, he just pulled back.”

UAE officials appeared, however, to have been more dismayed by the fact that Trump claimed he was 10 minutes away from striking Iran but did not inform his Emirati allies, diplomats say.

Emirati officials won’t comment on whether they will allow the United States to launch attacks on Iran in the event of a war. They have not yet committed to support a quest by U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to form a global maritime security force under U.S. command to secure the safety of shipping.

That has fed speculation about where the UAE stands in the dispute, said Karasik, the analyst. “It’s the big question. Is the UAE breaking away from the U.S.?” he said. “There are domestic economic problems and divisions over what do about Iran. But at the end of the day, the UAE sits under the American security umbrella, and that is what matters.

US Sanctions Turn Iran’s Oil Industry Into Spy vs Spy

By Farnaz Fassihi – 8 August 2019

They change offices every few months and store documents only in hard copy. They scan their businesses for covert listening devices and divert all office calls to their cellphones. They know they are under surveillance, and assume their electronics are hacked.

They are not spies or jewel thieves but Iran’s oil traders, and they are suddenly in the cross hairs of international intrigue and espionage.

“Sometimes I feel like I am an actor playing in a thriller spy movie,” said Meysam Sharafi, a veteran oil trader in Tehran.

Since President Trump imposed sanctions on Iranian oil sales last year, information on those sales has become a prized geopolitical weapon — coveted by Western intelligence agencies and top secret for Iran. And the business of selling Iranian oil, once a safe and lucrative enterprise for the well connected, has been transformed into a high-stakes global game of espionage and counterespionage.

Last month, Iran said it had dismantled a spy ring and arrested 17 Iranians it said were working for the C.I.A. The Iranian government was vague on the target of the espionage, for which some of the suspects were sentenced to death, but it now appears that it involved clandestine efforts to gather intelligence on oil sales.

President Trump denied that the suspects worked for the C.I.A., a highly unusual statement from a government that almost never confirms or denies such accusations. A spokesman for the C.I.A. declined to comment.

But American officials acknowledged that Iran’s oil sector is of intense interest to the United States and its intelligence agencies.

Whoever is doing the spying, there is little doubt that cloak-and-dagger tactics have buffeted the shrinking Iranian oil trade. Traders say they have been offered all kinds of enticements in exchange for information.

Eastern Europeans showed up in Tehran with cases of vodka and red wine, promising a steady flow of alcohol and cash and offering to double the broker’s fee. A man claiming to be an American academic offered a $5,000-a-month retainer for help with his research on the oil industry. Armenian prostitutes disguised as businesswomen proposed vacation getaways to Shiraz and Isfahan, ancient Iranian cities known for their history and culture.

The oil traders say foreigners, who they assume are working on behalf of the United States, have offered astronomical sums, ranging from $100,000 to $1 million, just for the bank account numbers the Oil Ministry used in a sale. Some of the foreigners have promised visas to the United States, the traders said.

One trader admitted to having been duped: The Armenian prostitutes persuaded him to use their names to register front companies in Armenia to facilitate banking transactions. After the women were caught soliciting clients in Iran, he said, Iranian security forces called him in for questioning and he ended the relationship.

Foreign clients, too, are paranoid because of the secondary sanctions that the United States would place on them if they are caught buying Iranian oil. Traders said that on trips abroad, clients asked them to switch hotels in the middle of the night. Traders said it was not uncommon to be questioned at airports overseas. In at least one case, a foreign customer dispatched female agents, dressed in tight dresses and heels, to test what information a trader might divulge.

If the spying charges were intended to send a message to Iran’s oil traders, the message was heard.

One trader said he called the intelligence branch of the Oil Ministry and proactively gave him some information about a suspicious European who had visited his office. Another deleted text messages and blocked the number of a woman who introduced herself as a Swedish Ph.D. student researching Iran’s oil trade.

Hassan Soleimani, the editor in chief of Mashregh, a newspaper affiliated with the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps, confirmed that the spy ring arrests involved oil espionage. So did an Iranian politician and two oil traders, all of whom spoke on condition of anonymity.

Many of the 17 people accused of spying had worked in the oil and energy sector as traders and brokers, the two traders said. They had come under scrutiny because of contacts with foreigners on their trips abroad.

Separately, Iran said in June that it had arrested a woman who worked at a European energy firm, accusing her of obtaining oil sales documents by cultivating senior and middle managers at the Oil Ministry.

Because Iran’s economy depends on oil, and on evading American sanctions, keeping oil sales secret is considered crucial.

“How we evade sanctions to sell our oil and how we move the money is now the country’s most vital and sensitive information,” Mr. Soleimani, the editor, said. “Nothing is more important.”

Iran’s oil minister, Bijan Zanganeh, banned the release of oil data last year after Washington quit the Iran nuclear deal and imposed sanctions on Iran’s oil exports and financial transactions.

“Information about Iran’s oil exports is war information,” he said in July.

Of the 10 people who on average contact the Oil Ministry each day to inquire about purchasing oil, Mr. Zanganeh has said, seven are not genuine customers. “They are after figuring out our entire system,” he told Iranian news media in June.

The White House said the aim of the sanctions, which were tightened in May, was “to bring Iran’s oil exports to zero, denying the regime its principal source of revenue.”

While that goal has not been met, analysts estimate that Iran’s foreign oil sales have fallen steeply, from 2.5 million barrels a day before the first set of sanctions took effect in 2018 to about 500,000 barrels a day now.

The cold conflict has spilled into the seas, where Iran was blamed for sabotage attacks on six oil tankers, and the air, where the United States and Iran have each downed the other’s drone.

Last month, Britain seized an Iranian tanker in Gibraltar that it said was destined for Syria in violation of international sanctions against Syria. Iran retaliated by seizing a British tanker in the Persian Gulf, a pointed reminder that any military effort to enforce the oil sanctions could quickly heat up.

The information war has been quieter but no less vital. Information about Iran’s oil production, prices, sales and exports are a crucial tool for Washington to gauge the effect of the sanctions and carry out its “maximum pressure” campaign against Iran.

“The U.S. wants the information on oil exports so they can have a sense of how much hard currency Iran is earning,” said Elizabeth Rosenberg, an analyst at the Center for a New American Security and a former senior Treasury official in the Obama administration. “Then they can have a sense of how much they have to squeeze Iran to get its leaders to change their political calculus.”

Iran is a tough intelligence target because Iranians work through “personal relationships of trust,” she said, avoiding some of the telltale trappings and mechanisms of the international oil trade and operating with extreme discretion.

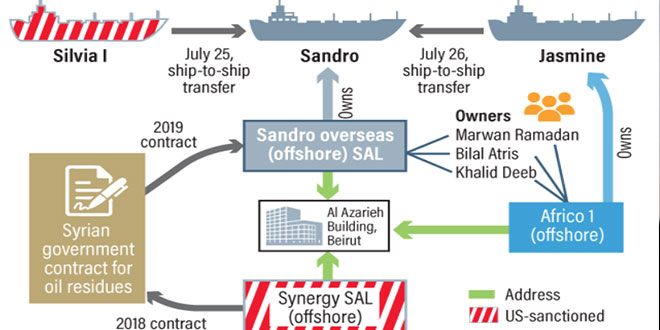

Iran has adopted an array of measures to circumvent sanctions, say traders and oil experts, including turning off the GPS locaters on its oil tankers, transferring oil from ship to ship in open waters, mixing its oil with Iraqi oil leaving the port of Basra, and falsifying shipping manifests to reflect a non-Iranian origin.

Iran has also tightened its oil trading system and increased security to make it more difficult to penetrate and track. Three Iranian oil traders described the changes to The New York Times, requesting anonymity over concerns for their safety.

The thousands of freestyle brokers who put together oil deals between buyers and the Oil Ministry were replaced by a handful of authorized, vetted traders. They report to four senior retired Oil Ministry officials, who have divided the market by region.

A former oil minister and Revolutionary Guards commander, Rostam Ghasemi, took charge of exports to Syria. The other three handled China, India and Europe.

Each purchase plan is customized depending on who is buying, how much they are buying and where the cargo is going — with the goal of constantly changing the method to elude sanctions monitors.

Buyers were required to send representatives to Tehran as a way to protect information and to identify serious clients.

Traders were ordered not to discuss price, shipping or payment with prospective clients. Their main job is to determine whether prospective buyers are legitimate, and then send a proposal to one of the four senior officials.

The Oil Ministry’s security wing holds regular workshops and briefing sessions to train the traders on security and counterespionage tactics.

“The space surrounding us has become intensely security oriented,” said Mr. Sharafi, one of the traders.

To encourage buyers, Iran typically sells its oil about $4 a barrel under the market price. It requires a 10 percent down payment and full payment before allowing the oil barrels to be offloaded at destination ports.

The payment phase is the most closely guarded step. Overseas bank accounts are opened and closed within a few hours, just long enough to make deposits and transfers. While those transactions are taking place, traders and buyers are kept under surveillance at a guesthouse belonging to the Oil Ministry. They are served kebabs and Persian tea and their phones are confiscated to prevent leaks.

Once the deal is complete, they are free to leave.

Oil traders say the new system is doing its job.

“Our worst fears about the economy collapsing did not materialize,” said Farshad Toomaj, a former trader who consults for the Oil Ministry from Sweden. “Iran has become very creative and sophisticated in coming up with dynamic ways to sell oil.”

Iran Owns the Persian Gulf Now

The Trump administration’s nonresponse to Iranian aggression has sent an unmistakable message.

By: Steven Cook – AUGUST 1, 2019

It has long been an accepted fact within the U.S. foreign-policy community that if any country blocked or interfered with shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, the United States and its allies would use the awesome force at their disposal to defend freedom of navigation. Yet like so much else in this era, long-held truths and ironclad laws have turned out to be elaborate fictions.

The United States has invested great sums in the Middle East over many decades to undertake a few important tasks—notably protecting the sea lines—but this task does not seem to be something the current president believes to be a core American interest. After all, on June 24, President Donald Trump tweeted: “China gets 91% of its Oil from the Straight, Japan 62%, & many other countries likewise. So why are we protecting the shipping lanes for other countries (many years) for zero compensation. All of these countries should be protecting their own ships on what has always been a dangerous journey.”

Anyone who still believes that the United States is going to challenge Iran directly should reread Trump’s tweet. It is more than that, however. It is a harbinger of what is to come in U.S. foreign policy.

The United States is leaving the Persian Gulf. Not this year or next, but there is no doubt that the United States is on its way out. Aside from the president’s tweet, the best evidence of the coming American departure from the region is Washington’s inaction in the face of Iran’s provocations.

Officials and analysts will often counter this, conjuring the number of personnel, planes, and ships the United States maintains in and around the Gulf, but leaders in Riyadh, Abu Dhabi, Doha, Manama, and Muscat understand what is happening. They have been worrying about the U.S. commitment to their security for some time and have been hedging against an American departure in a variety of ways, including by making overtures to China, Russia, Iran, and Turkey. On Wednesday, the Emiratis and Iranians met for the first time in six years to discuss maritime security in the Gulf. That is a positive development. And while both sides insist the meeting was routine and low-level, there is no doubt that American inaction has officials in Abu Dhabi rethinking how to deal with the Iranian challenge, which may run counter to U.S. efforts to isolate Tehran.

By all measures, the Persian Gulf had been quiet since Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) took nine American sailors and a naval officer for less than 24 hours after their two small vessels crossed into Iranian territorial water in January 2016. Things changed in May, however. Since then, the United States and others allege that Iranian forces have attacked six oil tankers; IRGC naval forces attempted to impede a British vessel traversing the Strait of Hormuz; the Iranians shot down an American drone; the United States shot down an Iranian drone; and the Iranians have taken the British-flagged oil tanker Stena Impero. (There were two other vessels that the Iranians briefly stopped but permitted to continue on their way.) The impounding of the Stena Impero is a direct response to the British seizure of an Iranian-flagged supertanker on July 4 near Gibraltar on suspicion that it was bound for Syria.