November 18 2019

In MID-OCTOBER, with unrest swirling in Baghdad, a familiar visitor slipped quietly into the Iraqi capital. The city had been under siege for weeks, as protesters marched in the streets, demanding an end to corruption and calling for the ouster of the prime minister, Adil Abdul-Mahdi. In particular, they denounced the outsize influence of their neighbor Iran in Iraqi politics, burning Iranian flags and attacking an Iranian consulate.

The visitor was there to restore order, but his presence highlighted the protesters’ biggest grievance: He was Maj. Gen. Qassim Suleimani, head of Iran’s powerful Quds Force, and he had come to persuade an ally in the Iraqi Parliament to help the prime minister hold on to his job.

It was not the first time Suleimani had been dispatched to Baghdad to do damage control. Tehran’s efforts to prop up Abdul-Mahdi are part of its long campaign to maintain Iraq as a pliable client state.

Now leaked Iranian documents offer a detailed portrait of just how aggressively Tehran has worked to embed itself into Iraqi affairs, and of the unique role of Suleimani. The documents are contained in an archive of secret Iranian intelligence cables obtained by The Intercept and shared with the New York Times for this article, which is being published simultaneously by both news organizations.

The unprecedented leak exposes Tehran’s vast influence in Iraq, detailing years of painstaking work by Iranian spies to co-opt the country’s leaders, pay Iraqi agents working for the Americans to switch sides, and infiltrate every aspect of Iraq’s political, economic, and religious life.

Many of the cables describe real-life espionage capers that feel torn from the pages of a spy thriller. Meetings are arranged in dark alleyways and shopping malls or under the cover of a hunting excursion or a birthday party. Informants lurk at the Baghdad airport, snapping pictures of American soldiers and keeping tabs on coalition military flights. Agents drive meandering routes to meetings to evade surveillance. Sources are plied with gifts of pistachios, cologne, and saffron. Iraqi officials, if necessary, are offered bribes. The archive even contains expense reports from intelligence ministry officers in Iraq, including one totaling 87.5 euros spent on gifts for a Kurdish commander.

According to one of the leaked Iranian intelligence cables, Abdul-Mahdi, who in exile worked closely with Iran while Saddam Hussein was in power in Iraq, had a “special relationship with the IRI” — the Islamic Republic of Iran — when he was Iraq’s oil minister in 2014. The exact nature of that relationship is not detailed in the cable, and, as one former senior U.S. official cautioned, a “special relationship could mean a lot of things — it doesn’t mean he is an agent of the Iranian government.” But no Iraqi politician can become prime minister without Iran’s blessing, and Abdul-Mahdi, when he secured the premiership in 2018, was seen as a compromise candidate acceptable to both Iran and the United States.

The leaked cables offer an extraordinary glimpse inside the secretive Iranian regime. They also detail the extent to which Iraq has fallen under Iranian influence since the American invasion in 2003, which transformed Iraq into a gateway for Iranian power, connecting the Islamic Republic’s geography of dominance from the shores of the Persian Gulf to the Mediterranean Sea.

The trove of leaked Iranian intelligence reports largely confirms what was already known about Iran’s firm grip on Iraqi politics. But the reports reveal far more than was previously understood about the extent to which Iran and the United States have used Iraq as a staging area for their spy games. They also shed new light on the complex internal politics of the Iranian government, where competing factions are grappling with many of the same challenges faced by American occupying forces as they struggled to stabilize Iraq after the United States invasion.

And the documents show how Iran, at nearly every turn, has outmaneuvered the United States in the contest for influence.

The archive is made up of hundreds of reports and cables written mainly in 2014 and 2015 by officers of Iran’s Ministry of Intelligence and Security, or MOIS, who were serving in the field in Iraq. The intelligence ministry, Iran’s version of the CIA, has a reputation as an analytical and professional agency, but it is overshadowed and often overruled by its more ideological counterpart, the Intelligence Organization of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which was formally established as an independent entity in 2009 at the order of Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

In Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria, which Iran considers crucial to its national security, the Revolutionary Guards — and in particular its elite Quds Force, led by Suleimani — determine Iran’s policies. Ambassadors to those countries are appointed from the senior ranks of the Guards, not the foreign ministry, which oversees the intelligence ministry, according to several advisers to current and past Iranian administrations. Officers from the intelligence ministry and from the Revolutionary Guards in Iraq worked parallel to one another, said these sources. They reported their findings back to their respective headquarters in Tehran, which in turn organized them into reports for the Supreme Council of National Security.

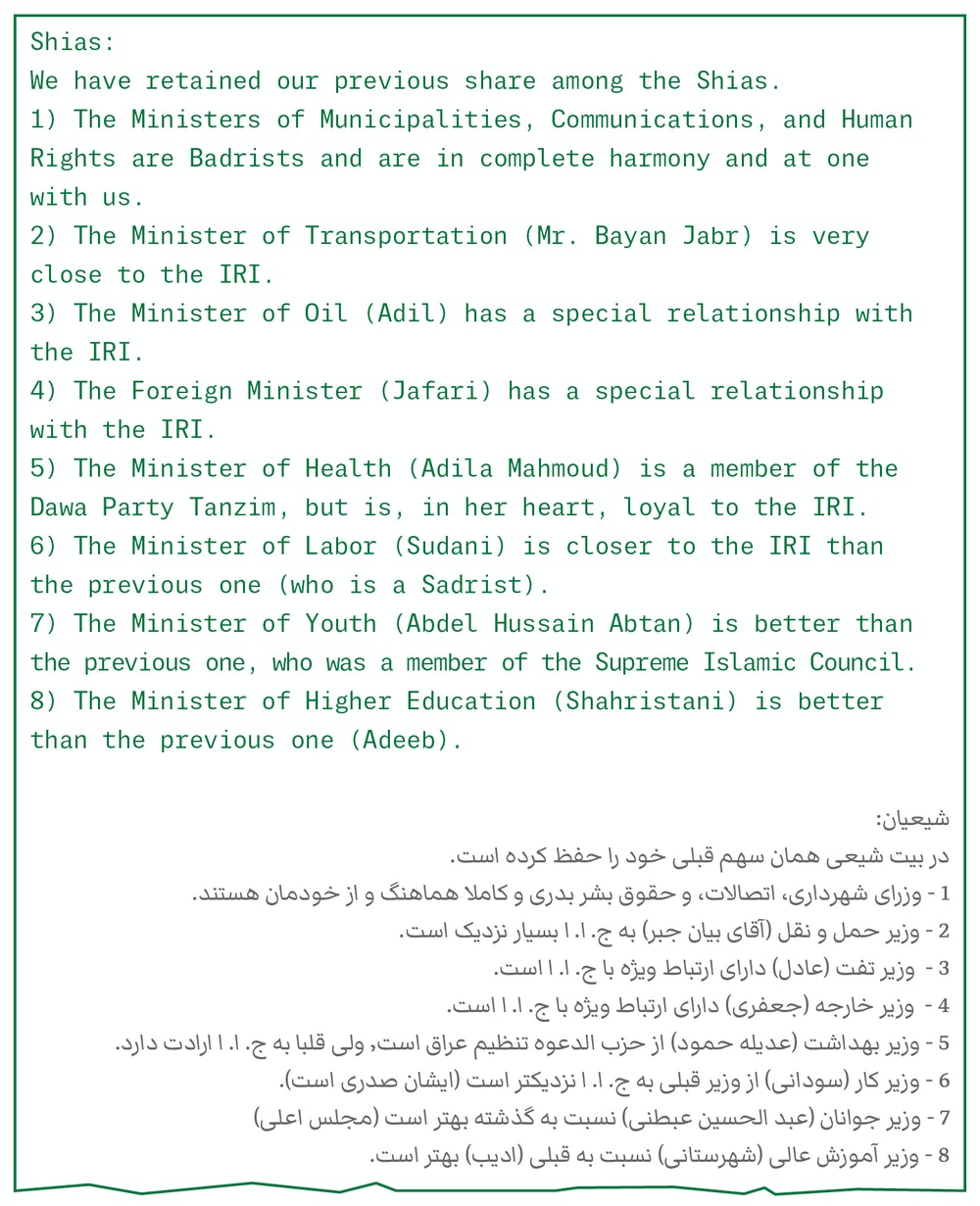

Cultivating Iraqi officials was a key part of their job, and it was made easier by the alliances many Iraqi leaders forged with Iran when they belonged to opposition groups fighting Saddam. Many of Iraq’s foremost political, military, and security officials have had secret relationships with Tehran, according to the documents. The same 2014 cable that described Abdul-Mahdi’s “special relationship” also named several other key members of the cabinet of former Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi as having close ties with Iran.

A political analyst and adviser on Iraq to Iran’s government, Gheis Ghoreishi, confirmed that Iran has focused on cultivating high-level officials in Iraq. “We have a good number of allies among Iraqi leaders who we can trust with our eyes closed,” he said.

Three Iranian officials were asked to comment for this article, in queries that described the existence of the leaked cables and reports. Alireza Miryusefi, a spokesperson for Iran’s United Nations mission, said he was away until later this month. Majid Takht-Ravanchi, Iran’s U.N. ambassador, did not respond to a written request that was hand-delivered to his official residence. Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif did not respond to an emailed request.

When reached by telephone, Hassan Danaiefar, Iran’s ambassador to Iraq from 2010 to 2017 and a former deputy commander of the Revolutionary Guards’ naval forces, declined to directly address the existence of the cables or their release, but he did suggest that Iran had the upper hand in information gathering in Iraq. “Yes, we have a lot of information from Iraq on multiple issues, especially about what America was doing there,” he said. “There is a wide gap between the reality and perception of U.S. actions in Iraq. I have many stories to tell.” He declined to elaborate.

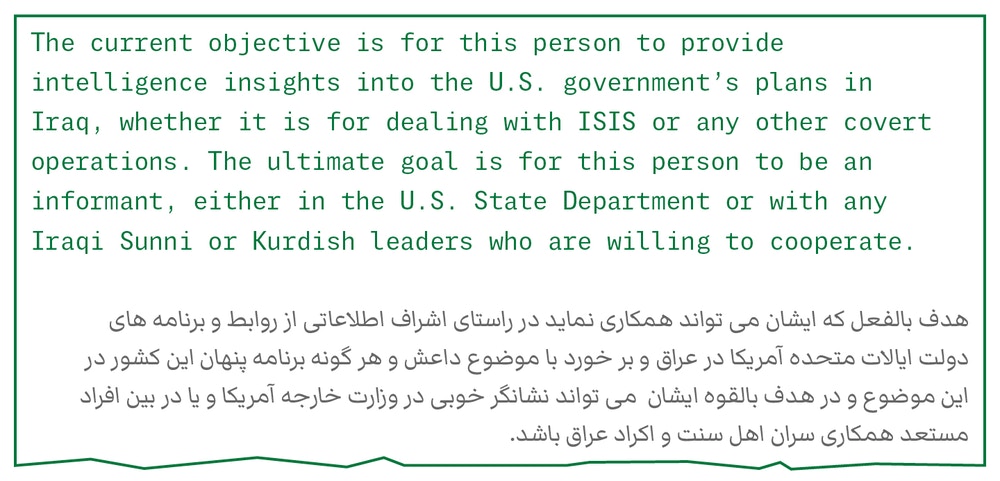

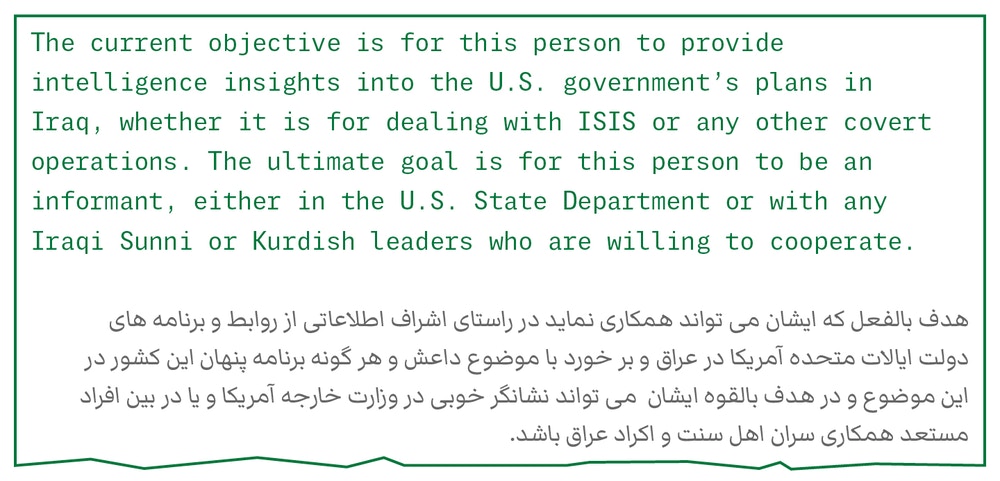

According to the reports, after the American troop withdrawal in 2011, Iran moved quickly to add former CIA informants to its payroll. One undated section of an intelligence ministry cable shows that Iran began the process of recruiting a spy inside the State Department. It is unclear what came of the recruitment effort, but according to the files, Iran had started meeting with the source, and offered to reward the potential asset with a salary, gold coins, and other gifts. The State Department official is not named in the cable, but the person is described as someone who would be able to provide “intelligence insights into the U.S.

government’s plans in Iraq, whether it is for dealing with ISIS or any other covert operations.”

“The subject’s incentive in collaborating will be financial,” the report said.

The State Department declined to comment on the matter.

In interviews, Iranian officials acknowledged that Iran viewed surveillance of American activity in Iraq after the United States invasion as critical to its survival and national security. When American forces toppled Saddam, Iran swiftly moved some of its best officers from both the intelligence ministry and from the Intelligence Organization of the Revolutionary Guards to Iraq, according to the Iranian government advisers and a person affiliated with the Guards. President George W. Bush had declared Iran to be part of an “axis of evil,” and Iranian leaders believed that Tehran would be next on Washington’s list of regime-change capitals after Kabul and Baghdad.

700 PAGE DOCUMENT

AROUND THE WORLD, governments have had to contend with the occasional leak of secret communiqués or personal emails as a fact of modern life. Not so in Iran, where information is tightly controlled and the security services are widely feared.

The roughly 700 pages of leaked reports were sent anonymously to The Intercept, which translated them from Persian to English and shared them with the Times. The Intercept and the Times verified the authenticity of the documents but do not know who leaked them. The Intercept communicated over encrypted channels with the source, who declined to meet with a reporter. In these anonymous messages, the source said that they wanted to “let the world know what Iran is doing in my country Iraq.”

Like the internal communications of any spy service, some of the reports contain raw intelligence whose accuracy is questionable, while others appear to represent the views of intelligence officers and sources with their own agendas.

Some of the cables show bumbling and comical ineptitude, like one that describes the Iranian spies who broke into a German cultural institute in Iraq only to find they had the wrong codes and could not unlock the safes. Other officers were browbeaten by their superiors in Tehran for laziness, and for sending back to headquarters reports that relied only on news accounts.

But by and large, the intelligence ministry operatives portrayed in the documents appear patient, professional, and pragmatic. Their main tasks are to keep Iraq from falling apart; from breeding Sunni militants on the Iranian border; from descending into sectarian warfare that might make Shia Muslims the targets of violence; and from spinning off an independent Kurdistan that would threaten regional stability and Iranian territorial integrity. The Revolutionary Guards and Suleimani have also worked to eradicate the Islamic State, but with a greater focus on maintaining Iraq as a client state of Iran and making sure that political factions loyal to Tehran remain in power.

This portrait is all the more striking at a time of heightened tensions between the United States and Iran. Since 2018, when President Donald Trump pulled out of the Iran nuclear deal and reimposed sanctions, the White House has rushed ships to the Persian Gulf and reviewed military plans for war with Iran. In October, the Trump administration promised to send American troops to Saudi Arabia following attacks on oil facilities there for which Iran was widely blamed.

TELL THEM WE ARE AT YOUR SERVICE

WITH A SHARED FAITH and tribal affiliations that span a porous border, Iran has long been a major presence in southern Iraq. It has opened religious offices in Iraq’s holy cities and posted banners of Iran’s revolutionary leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, on its streets. It supports some of the most powerful political parties in the south, dispatches Iranian students to study in Iraqi seminaries, and sends Iranian construction workers to build Iraqi hotels and refurbish Iraqi shrines.

But while Iran may have bested the United States in the contest for influence in Baghdad, it has struggled to win popular support in the Iraqi south. Now, as the last six weeks of protests make clear, it is facing unexpectedly strong pushback. Across the south, Iranian-backed Iraqi political parties are seeing their headquarters burned and their leading operatives assassinated, an indication that Iran may have underestimated the Iraqi desire for independence not just from the United States, but also from its neighbor.

In a sense, the leaked Iranian cables provide a final accounting of the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq. The notion that the Americans handed control of Iraq to Iran when they invaded now enjoys broad support, even within the U.S. military.

A recent two-volume history of the Iraq War, published by the U.S. Army, details the campaign’s many missteps and its “staggering cost” in lives and money.

Nearly 4,500 American troops were killed, hundreds of thousands of Iraqis died, and American taxpayers spent up to $2 trillion on the war. The study, which totals hundreds of pages and draws on declassified documents, concludes: “An emboldened and expansionist Iran appears to be the only victor.”

Iran’s rise as a power player in Iraq was in many ways a direct consequence of Washington’s lack of any post-invasion plan. The early years following the fall of Saddam were chaotic, both in terms of security and in the lack of basic services like water and electricity. To most observers on the ground, it appeared as if the United States was shaping policy on the go, and in the dark.

Among the most disastrous American policies were the decisions to dismantle Iraq’s armed forces and to purge from government service or the new armed forces any Iraqi who had been a member of Saddam’s ruling Baath Party. This process, known as de-Baathification, automatically marginalized most Sunni men. Unemployed and resentful, they formed a violent insurgency targeting Americans and Shias seen as U.S. allies.

As sectarian warfare between Sunnis and Shias raged, the Shia population looked to Iran as a protector. When ISIS gained control of territory and cities, the Shias’ vulnerability and the failure of the United States to protect them fueled efforts by the Revolutionary Guards and Suleimani to recruit and mobilize Shia militias loyal to Iran.

According to the intelligence ministry documents, Iran has continued to take advantage of the opportunities the United States has afforded it in Iraq. Iran, for example, reaped an intelligence windfall of American secrets as the U.S. presence began to recede after its 2011 troop withdrawal. The CIA had tossed many of its longtime secret agents out on the street, leaving them jobless and destitute in a country still shattered from the invasion — and fearful that they could be killed for their links with the United States, possibly by Iran. Short of money, many began to offer their services to Tehran. And they were happy to tell the Iranians everything they knew about CIA operations in Iraq.

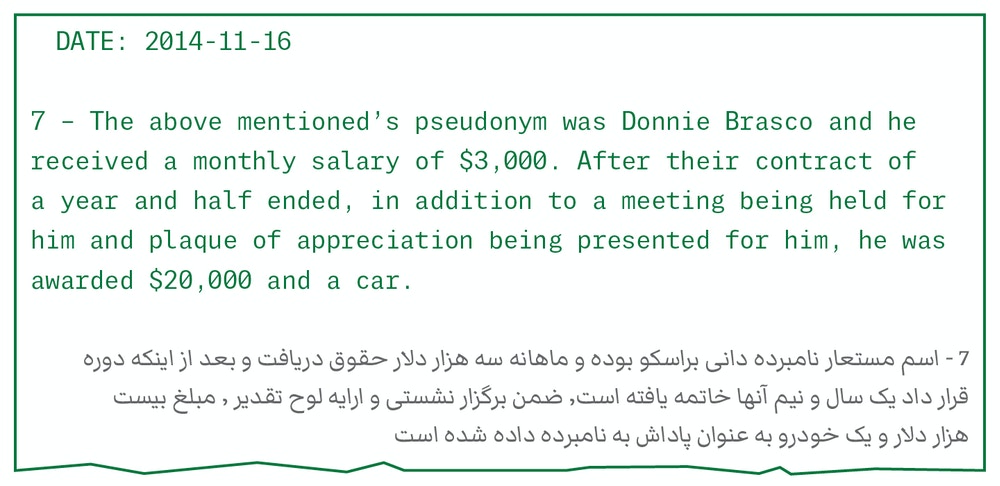

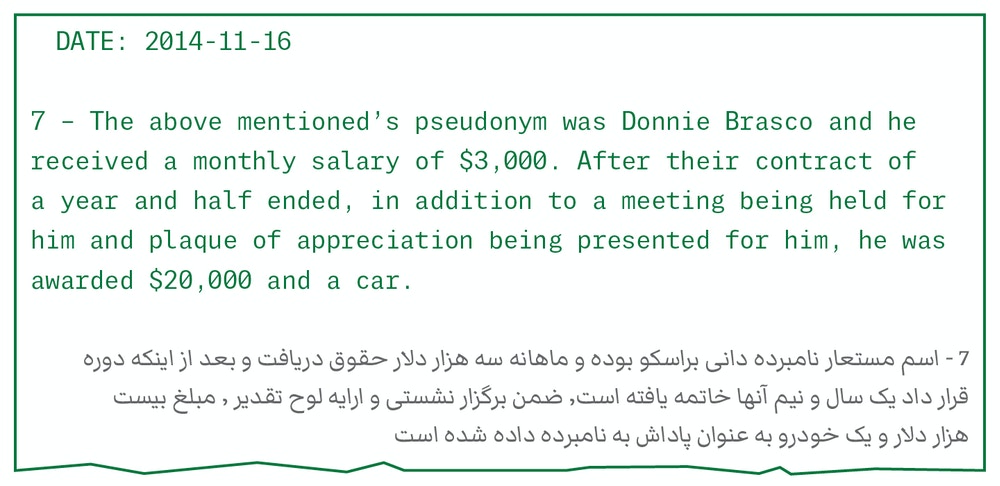

In November 2014, one of them, an Iraqi who had spied for the CIA, broke and terrified that his ties to the Americans would cost him his life, switched sides. The CIA, according to the cable, had known the man by a nickname: “Donnie Brasco.” His Iranian handler would call him, simply, “Source 134992.”

Turning to Iran for protection, he said that everything he knew about American intelligence gathering in Iraq was for sale: the locations of CIA safe houses; the names of hotels where CIA operatives met with agents; details of his weapons and surveillance training; the names of other Iraqis working as spies for the Americans.

Source 134992 told the Iranian operatives that he had worked for the agency for 18 months starting in 2008, on a program targeting Al Qaeda. He said he had been paid well for his work — $3,000 per month, plus a one-time bonus of $20,000 and a car.

But swearing on the Quran, he promised that his days of spying for the United States were over, and agreed to write a full report for the Iranians on everything he knew from his time with the CIA.

“I will turn over to you all the documents and videos that I have from my training course,” the Iraqi man told his Iranian handler, according to a 2014 Iranian intelligence report. “And pictures and identifying features of my fellow trainees and my subordinates.”

The CIA declined to comment.

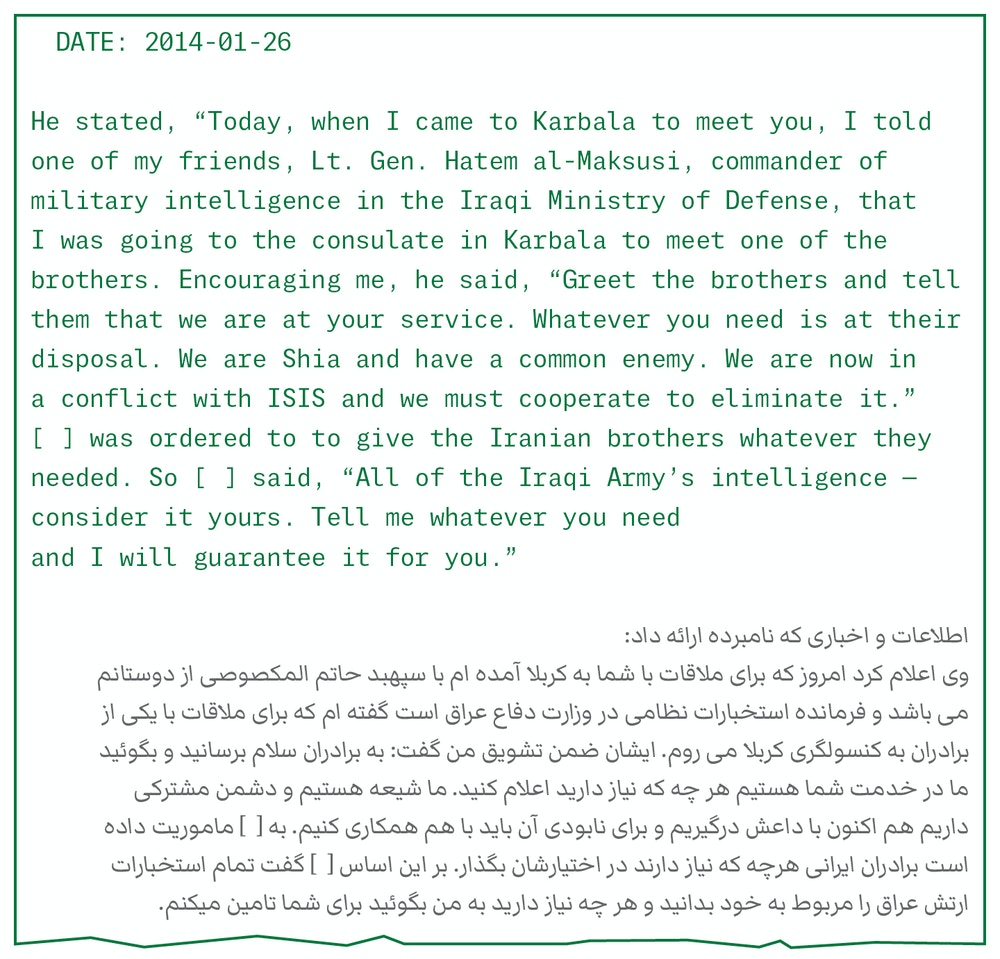

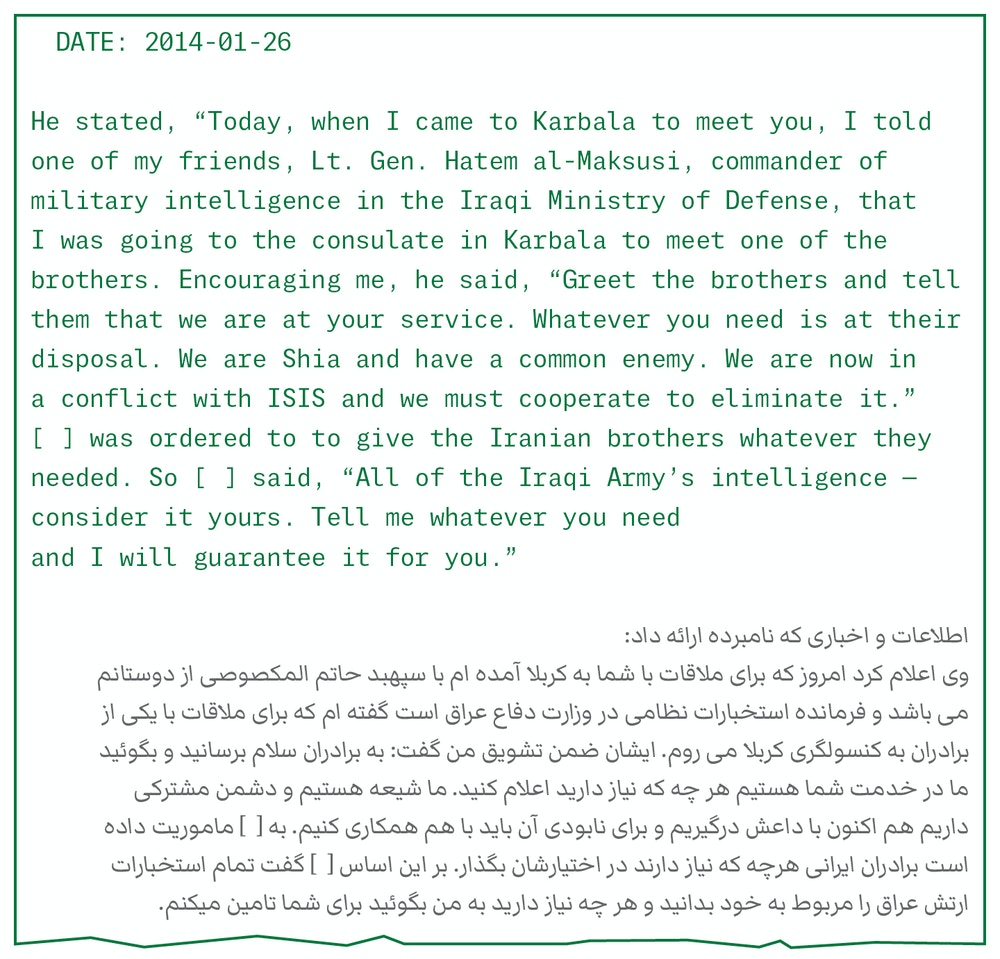

Iranian spies, Iraqi officials say, are everywhere in the south, and the region has long been a beehive of espionage. It was there, in Karbala in late 2014, that an Iraqi military intelligence officer, down from Baghdad, met with an Iranian intelligence official and offered to spy for Iran — and to tell the Iranians whatever he could about American activities in Iraq.

“Iran is my second country and I love it,” the Iraqi official told the Iranian officer, according to one of the cables. In a meeting that lasted more than three hours, the Iraqi told of his devotion to the Iranian system of government, in which clerics rule directly, and his admiration for Iranian movies.

He said he had come with a message from his boss in Baghdad, Lt. Gen. Hatem al-Maksusi, then commander of military intelligence in the Iraqi Ministry of Defense: “Tell them we are at your service. Whatever you need is at their disposal. We are Shia and have a common enemy.”

Maksusi’s messenger continued, “All of the Iraqi Army’s intelligence — consider it yours.” He told the Iranian intelligence officer about secret targeting software the United States had provided to the Iraqis, and offered to turn it over to the Iranians. “If you have a new laptop, give it to me so I can upload the program onto it,” he said.

And there was more, he said. The United States had also given Iraq a highly sensitive system for eavesdropping on mobile phones, which was run out of the prime minister’s office and the headquarters of Iraqi military intelligence. “I will put at your disposal whatever intelligence about it you want,” he said.

In an interview, Maksusi disputed saying the things attributed to him in the cables and denied ever working for Iran. He praised Iran for its help in the fight against ISIS, but said he had also maintained a close relationship with the United States. “I worked for Iraq and did not work for any other state,” he said. “I was not the intelligence director for the Shias, but I was intelligence director for all of Iraq.”

When asked about the cable, a former American official said the United States had become aware of the Iraqi military intelligence officer’s ties to Iran and had limited his access to sensitive information.

THE AMERICAN’S CANDIDATE

By late 2014, the United States was once again pouring weapons and soldiers into Iraq as it began battling the Islamic State. Iran, too, had an interest in defeating the militants. As ISIS took control of the west and the north, young Iraqi men traveled across the deserts and marshes of the south by the busload, heading to Iran for military training.

Some within the American and Iranian governments believed that the two rivals should coordinate their efforts against a common enemy. But Iran, as the leaked cables make clear, also viewed the increased American presence as a threat and a “cover” to gather intelligence about Iran.

“What is happening in the sky over Iraq shows the massive level of activity of the coalition,” one Iranian officer wrote. “The danger for the Islamic Republic of Iran’s interests represented by their activity must be taken seriously.”

The rise of ISIS was at the same time driving a wedge between the Obama administration and a large swath of the Iraqi political class. Barack Obama had pushed for the ouster of Prime Minister Nouri Kamal al-Maliki as a condition for renewed American military support. He believed that Maliki’s draconian policies and crackdowns on Iraqi Sunnis had helped lead to the rise of the militants.

Maliki, who had lived in exile in Iran in the 1980s, was a favorite of Tehran’s. His replacement, the British-educated Haider al-Abadi, was seen as more friendly to the West and less sectarian. Facing the uncertainty of a new prime minister, Hassan Danaiefar, then Iran’s ambassador, called a secret meeting of senior staffers at the Iranian Embassy, a hulking, fortified structure just outside Baghdad’s Green Zone.

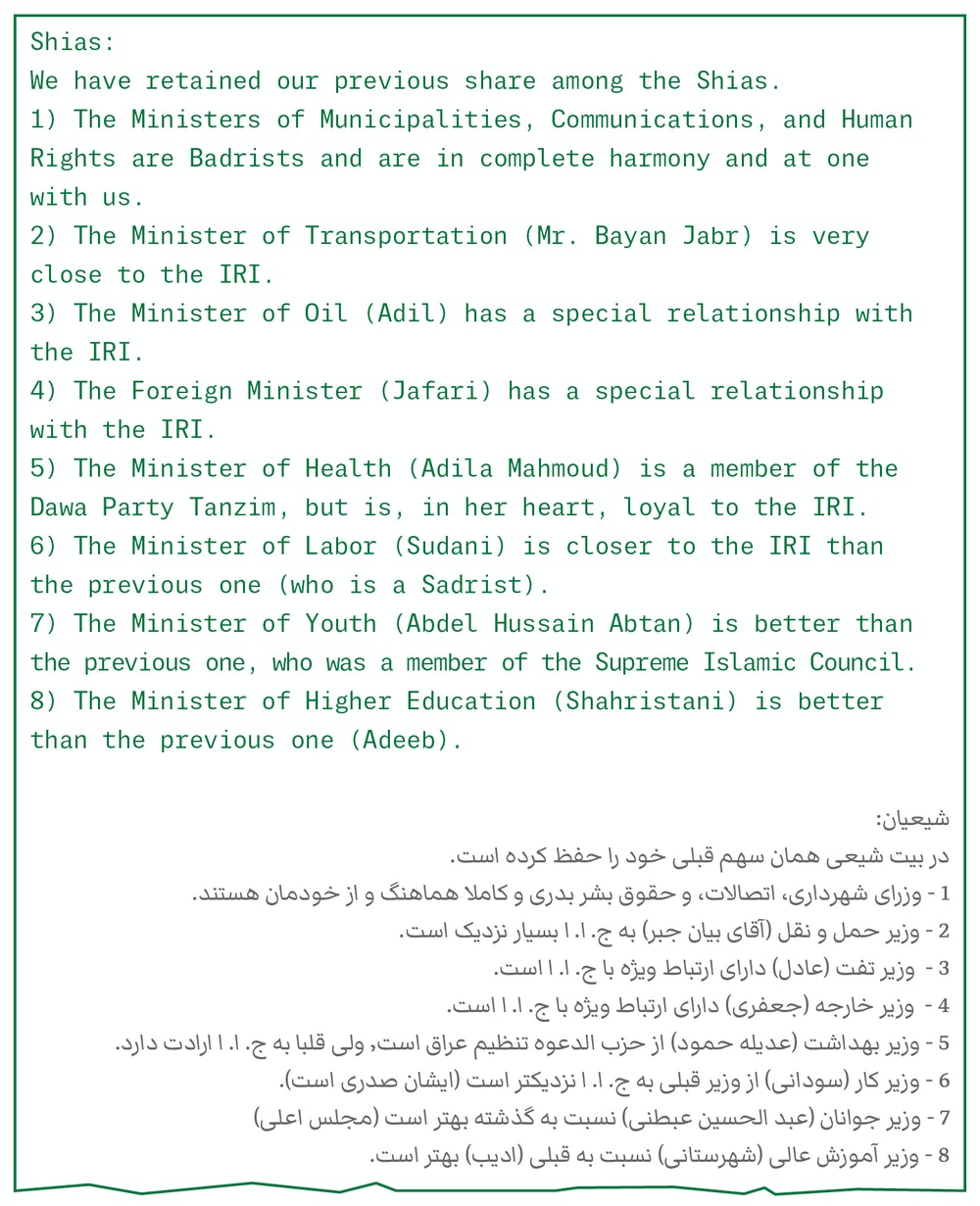

As the meeting progressed, it became clear that the Iranians had little cause to worry about the new Iraqi government. Abadi was dismissed as “a British man,” and “the Americans’ candidate,” but the Iranians believed that they had plenty of other ministers in their pocket.

One by one, Danaiefar went down the list of cabinet members, describing their relationships to Iran.

Ibrahim al-Jafari — who had previously served as Iraqi prime minister and by late 2014 was the foreign minister — was, like Abdul-Mahdi, identified as having a “special relationship” with Iran. In an interview, Jafari did not deny that he had close relations with Iran, but said he had always dealt with foreign countries based on the interests of Iraq.

Iran counted on the loyalty of many lesser cabinet members as well.

The report said the ministers of municipalities, communications, and human rights “are in complete harmony and at one with us and are our people.” The environment minister, it said, “works with us, although he is Sunni.” The transportation minister — Bayan Jabr, who had led the Iraqi Interior Ministry at a time when hundreds of prisoners were tortured to death with electric drills or summarily shot by Shia death squads — was deemed to be “very close” to Iran. When it came to Iraq’s education minister, the report says, “we will have no problem with him.”

The former ministers of municipalities, communications, and human rights were all members of the Badr Organization, a political and military group established by Iran in the 1980s to oppose Saddam. The former minister of municipalities denied having a close relationship with Iran; the former human rights minister acknowledged being close to Iran, and praised Iran for helping Shia Iraqis during Saddam’s dictatorship and for help defeating ISIS. The former minister of communications said that he served Iraq, not Iran, and that he maintained relationships with diplomats from many countries; the former minister of education said that he had not been supported by Iran and that he served at the request of Abadi. The former environment minister could not be reached for comment.

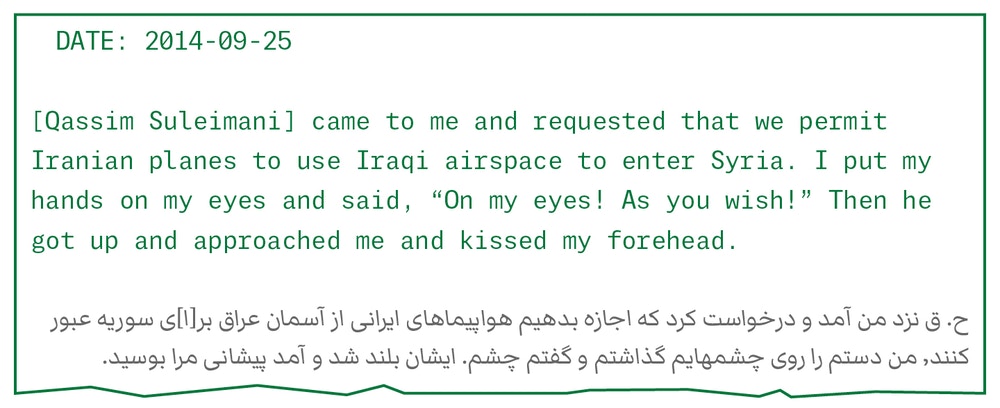

Iran’s dominance over Iraqi politics is vividly shown in one important episode from the fall of 2014, when Baghdad was a city at the center of a multinational maelstrom. The Syrian civil war was raging to the west, ISIS militants had seized almost a third of Iraq, and American troops were heading back to the region to confront the growing crisis.

Against this chaotic backdrop, Jabr, then the transportation minister, welcomed Suleimani, the Quds Force commander, to his office. Suleimani had come to ask a favor: Iran needed access to Iraqi airspace to fly planeloads of weapons and other supplies to support the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad in its fight against American-backed rebels.

It was a request that placed Jabr at the center of the longstanding rivalry between the United States and Iran. Obama administration officials had been lobbying hard to get the Iraqis to stop Iranian flights through their airspace, but face to face with the Quds chief, Iraq’s transportation minister found it impossible to refuse.

Suleimani, Jabr recalled, “came to me and requested that we permit Iranian airplanes to use Iraqi air space to pass on to Syria,” according to one of the cables. The transportation minister did not hesitate, and Suleimani appeared to be pleased. “I put my hands on my eyes and said, ‘On my eyes! As you wish!’” Jabr told the intelligence ministry officer. “Then he got up and approached me and kissed my forehead.”

Jabr confirmed the meeting with Suleimani, but said the flights from Iran to Syria carried humanitarian supplies and religious pilgrims traveling to Syria to visit holy sites, not weapons and military supplies to aid Assad as American officials believed.

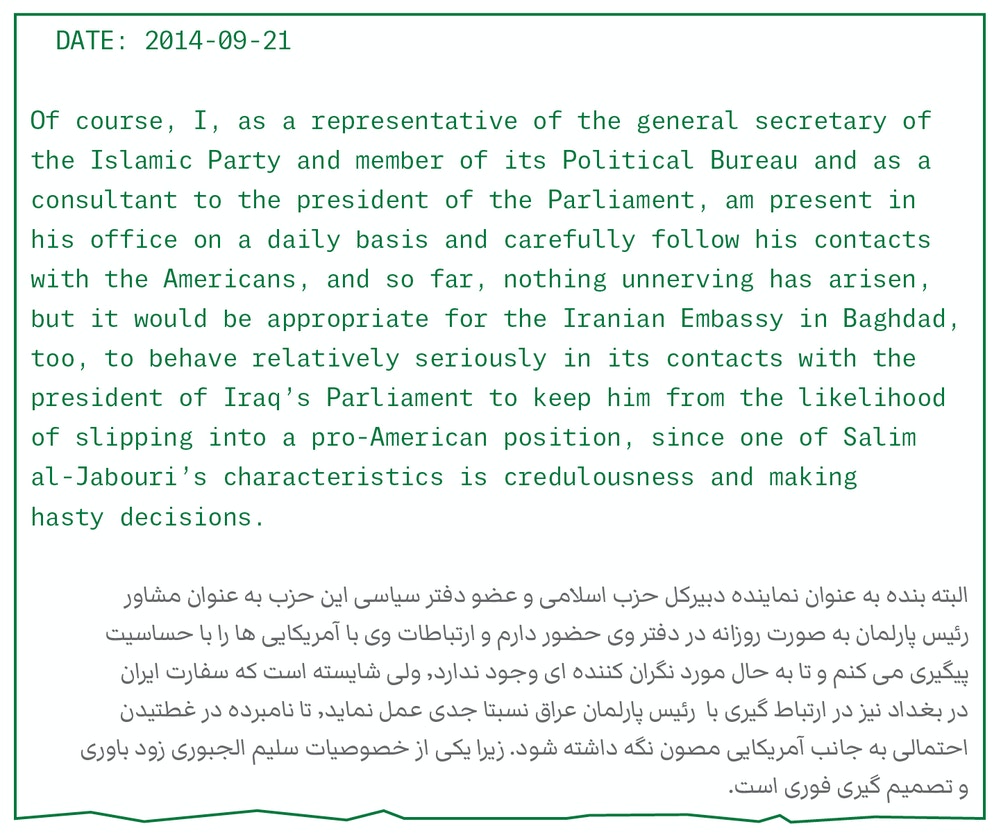

Meanwhile, Iraqi officials known to have a relationship with the United States came under special scrutiny, and Iran took measures to counter American influence. Indeed, many of the files show that as top American diplomats met behind closed doors with their Iraqi counterparts in Baghdad, their conversations were routinely reported back to the Iranians.

Throughout 2014 and 2015, as a new Iraqi government settled in, the American ambassador, Stuart Jones, met often with Salim al-Jabouri, who was speaker of the Iraqi Parliament until last year. Jabouri, although he is Sunni, was known to have a close relationship with Iran, but the files now reveal that one of his top political advisers — identified as Source 134832 — was an Iranian intelligence asset. “[I] am present in his office on a daily basis and carefully follow his contacts with the Americans,” the source told his Iranian handler. Jabouri, in an interview, said he did not believe that anyone on his staff had worked as an agent for Iran, and that he fully trusted his aides. (Jones declined to comment.)

The source urged the Iranians to develop closer ties to Jabouri, to blunt American efforts to nurture a new class of younger Sunni leaders in Iraq and perhaps bring about reconciliation between Sunnis and Shias. The source warned that Iran should act to keep the parliament speaker from “slipping into a pro-American position, since one of Salim al-Jabouri’s characteristics is credulousness and making hasty decisions.”

Another report reveals that Nechervan Barzani, then the prime minister of Kurdistan, met with top American and British officials and Abadi, the Iraqi prime minister, in Baghdad in December 2014, and then went almost immediately to meet with an Iranian official to tell him everything. Through a spokesperson, Barzani said he did not recall meeting with any Iranian officials at the time and described the cable as “baseless and unfounded.” He said he “absolutely denies” telling the Iranians details about his conversations with American and British diplomats.

Sometimes, the Iranians also saw trade value in the information they received from their Iraqi sources.

One report from the Jabouri adviser revealed that the United States was interested in gaining access to a rich natural gas field in Akkas, near Iraq’s border with Syria. The source explained that the Americans might eventually try to export the natural gas to Europe, a major market for Russian natural gas. Intrigued, the intelligence ministry officer, in a cable to Tehran, wrote, “It is recommended that the aforementioned information be used in exchange with the Russians and Syria.” The cable was written just as Russia was significantly stepping up its involvement in Syria, and as Iran continued its military buildup there, in support of Assad.

And although Iran was initially suspicious of Abadi’s allegiances, a report written a few months after his rise to the premiership suggested that he was quite willing to have a confidential relationship with Iranian intelligence. A January 2015 report details a private meeting between Abadi and an intelligence ministry officer known as Boroujerdi, held in the prime minister’s office “without the presence of a secretary or a third person.”

During the meeting, Boroujerdi homed in on Iraq’s Sunni-Shia divide, probing Abadi’s feelings on perhaps the most sensitive subject in Iraqi politics. “Today, the Sunnis find themselves in the worst possible circumstances and have lost their self-confidence,” the intelligence officer opined, according to the cable. “The Sunnis are vagrants, their cities are destroyed and an unclear future awaits them, while the Shias can retrieve their self-confidence.”

Iraq’s Shia were “at a historical turning point,” Boroujerdi continued. The Iraqi government and Iran could “take advantage of this situation.”

According to the cable, the prime minister expressed his “complete agreement.” Abadi declined to comment.

SWEETNESS INTO BITTERNESS

EVER SINCE THE start of the Iraq War in 2003, Iran has put itself forward as the protector of Iraq’s Shias, and Suleimani, more than anyone else, has employed the dark arts of espionage and covert military action to ensure that Shia power remains ascendant. But it has come at the cost of stability, with Sunnis perennially disenfranchised and looking to other groups, like the Islamic State, to protect them.

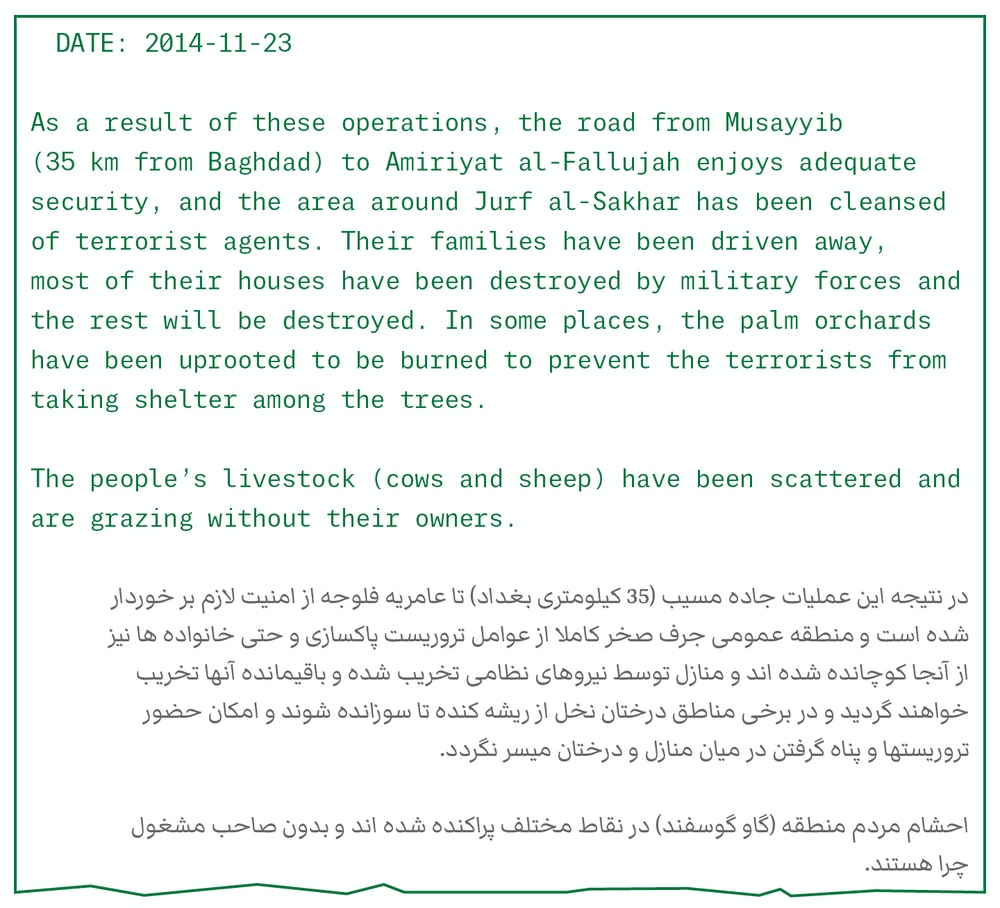

A 2014 massacre of Sunnis in the farming community of Jurf al-Sakhar was a vivid example of the kinds of sectarian atrocities committed by armed groups loyal to Iran’s Quds Force that had alarmed the United States throughout the Iraq War, and undermined efforts at reconciliation. As the field reports make clear, some of the Americans’ concerns were shared by the Iranian intelligence ministry. That signaled divisions within Iran over its Iraq policies between more moderate elements under President Hassan Rouhani and militant factions like the Revolutionary Guards.

Jurf al-Sakhar, which lies just east of Fallujah in the Euphrates River Valley, is lush with orange trees and palm groves. It was overrun by the Islamic State in 2014, giving militants a foothold from which they could launch attacks on the holy cities of Karbala and Najaf.

Jurf al-Sakhar is also important to Iran because it lies on a route Shia religious pilgrims use to travel to Karbala during Muharram, the monthlong commemoration of the death of Prophet Muhammad’s grandson, Imam Hussein, a revered figure for Shias.

When Shia militias supported by Iran drove the militants out of Jurf al-Sakhar in late 2014, the first major victory over ISIS, it became a ghost town. It was no longer a threat to the thousands of Shia pilgrims who would pass by, but Iran’s victory came at a high cost to the town’s Sunni residents. Tens of thousands were displaced, and a local politician, the only Sunni member on the provincial council, was found with a bullet hole through his head.

One cable describes the damage in almost biblical terms. “As a result of these operations,” its author reported, “the area around Jurf al-Sakhar has been cleansed of terrorist agents. Their families have been driven away, most of their houses have been destroyed by military forces and the rest will be destroyed. In some places, the palm orchards have been uprooted to be burned to prevent the terrorists from taking shelter among the trees. The people’s livestock (cowsand sheep) have been scattered and are grazing without their owners.”

The Jurf al-Sakhar operation and other bloody actions led by Iran’s proxies and directed by Tehran further alienated Iraq’s Sunni population, according to one report, which notes that “destroying villages and houses, looting the Sunnis’ property and livestock turned the sweetness of these successes” against ISIS into “bitterness.” One of the Jurf al-Sakhar cables cast the impact of Shia militias in particularly stark terms: “In all the areas where the Popular Mobilization Forces go into action, the Sunnis flee, abandoning their homes and property, and prefer to live in tents as refugees or reside in camps.”

The intelligence ministry feared that Iran’s gains in Iraq were being squandered because Iraqis so resented the Shia militias and the Quds Force that sponsored them. Above all, its officers blamed Suleimani, whom they saw as a dangerous self-promoter using the anti-ISIS campaign as a launching pad for a political career back home in Iran. One report, which states at the top that it is not to be shared with the Quds Force, criticizes the general personally for publicizing his leading role in the military campaign in Iraq by “publishing pictures of himself on different social media sites.”

Doing that had made it obvious that Iran controlled the dreaded Shia militias — a potential gift to its rivals. “This policy of Iran in Iraq,” the report said, “has allowed the Americans to return to Iraq with greater legitimacy. And groups and individuals who had been fighting against the Americans among the Sunnis are now wishing that not only America, but even Israel, would enter Iraq and save Iraq from Iran’s clutches.”

11-29-2014

At times, the Iranians sought to counter the ill will generated by their presence in Iraq with soft-power campaigns similar to American battlefield efforts to win “hearts and minds.” Hoping to gain a “propaganda advantage and restore Iran’s image among the people,” Iran devised a plan to send pediatricians and gynecologists to villages in northern Iraq to administer health services, according to one field report. It is not clear, however, if that initiative materialized.

Just as often, Iran would use its influence to close lucrative development deals. With Iraq dependent on Iran for military support in the fight against ISIS, one cable shows the Quds Force receiving oil and development contracts from Iraq’s Kurds in exchange for weapons and other aid. In the south, Iran was awarded contracts for sewage and water purification by paying a $16 million bribe to a member of Parliament, according to another field report.

Today, Iran is struggling to maintain its hegemony in Iraq, just as the Americans did after the 2003 invasion. Iraqi officials, meanwhile, are increasingly worried that a provocation in Iraq on either side could set off a war between the two powerful countries vying for dominance in their homeland. Against this geopolitical backdrop, Iraqis learned long ago to take a pragmatic approach to the overtures of Iran’s spies — even Sunni Iraqis who view Iran as an enemy.

“Not only doesn’t he believe in Iran, but he doesn’t believe that Iran might have positive intentions toward Iraq,” one Iranian case officer wrote in late 2014, about an Iraqi intelligence recruit described as a Baathist who had once worked for Saddam and later the CIA. “But he is a professional spy and understands the reality of Iran and the Shia in Iraq and will collaborate to save himself.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community