Writer Liana Aghajanian Photographer Steve Eggleston & Tino Zahedi

Discover the glamorous ghost of parties past at Iran’s long-abandoned US embassy

Architect: Unknown

Date: 1959

For nearly 40 years, the Iranian Embassy in Washington DC has remained eerily vacant. Just across the street from the Brazilian Embassy and flanked by large trees, it now stands as a piece of lost history, seemingly frozen in time as the world around it moves on.

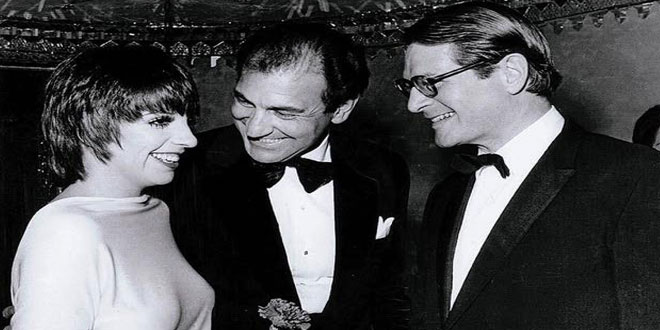

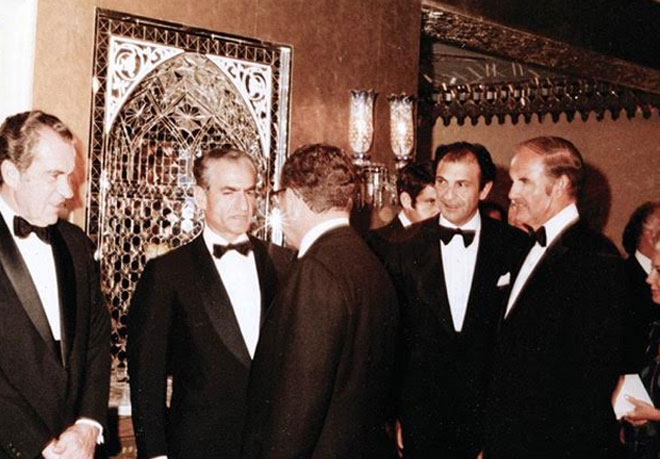

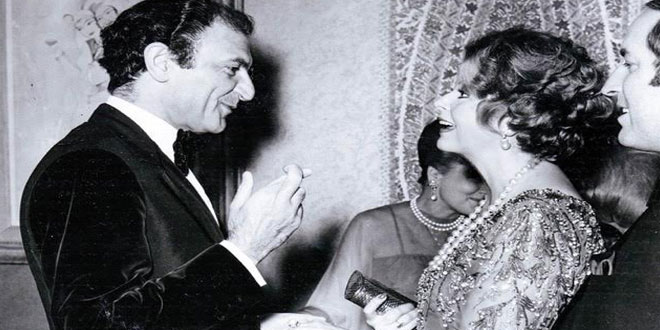

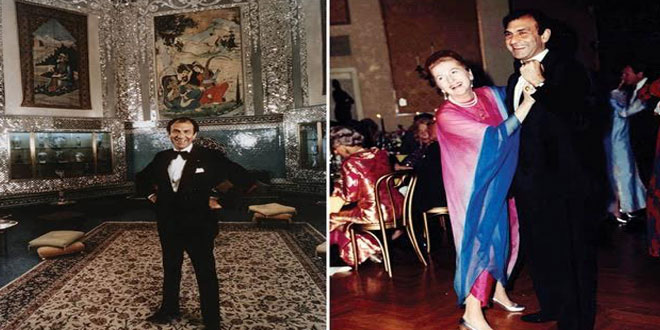

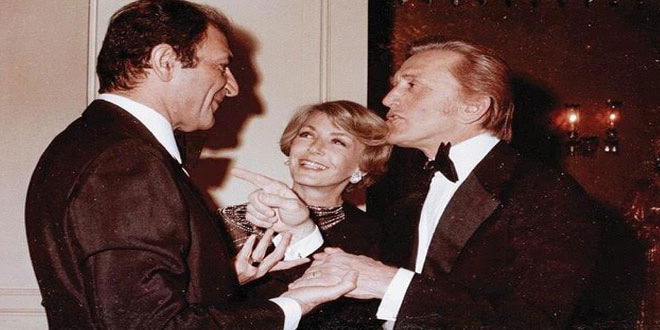

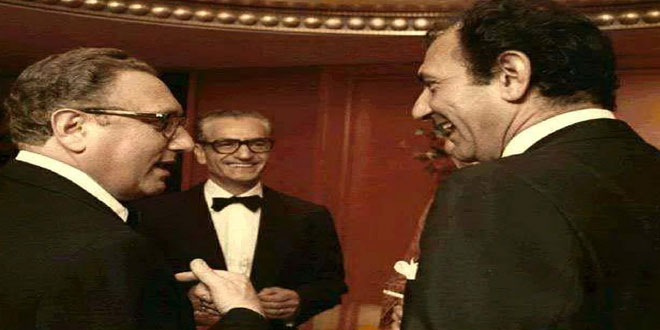

In its heyday, however, when the US and Iran maintained rather friendly relations during the 1960s and 1970s, there was no other place in the country’s capital to be than 3005 Massachusetts Avenue. Back then, Iranian Ambassador Ardeshir Zahedi entertained everyone from Elizabeth Taylor and Frank Sinatra to Henry Kissinger and Andy Warhol at lavish parties held in the impeccably furnished embassy.

“It was Washington’s party place. If you got an invitation to the Iranian Embassy, you had made it”

“It’s like this mid-century Persian structure in the middle of Washington”

Decorated by the late Hungarian-born, London-based designer Michael Szell, the embassy was outfitted with an impressive mix of Iranian cultural motifs and French Second Empire details. Szell, who counted Queen Elizabeth II of England as a client, worked closely with Zahedi to achieve the look.

Steve Eggleston, a photojournalist whose beat in the 1970s included the receptions and parties of Massachusetts Avenue (known as ‘Embassy Row’) says that the Iranian Embassy was the place to go to in Washington DC for a party; the refreshments flowed, the atmosphere was light-hearted and Zahedi spared no expense when it came to entertaining his guests.

‘It was Washington’s party place. If you got an invitation to the Iranian Embassy, you had made it,’ he says. Eggleston first attended Zahedi’s notorious parties at a reception honouring Queen Noor of Jordan, and would often run into Henry Kissinger during subsequent visits, in rooms decorated with rich Persian rugs from regions across Iran.

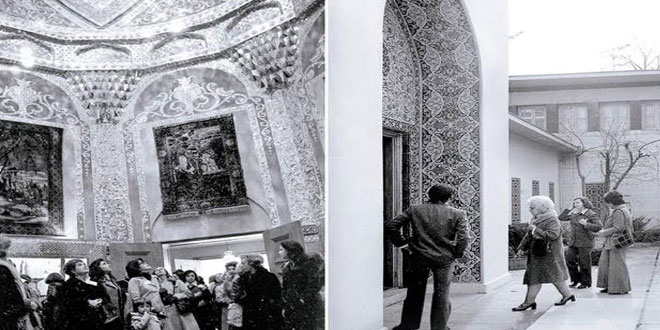

The most legendary suite of the embassy was the Persian Room, or ‘Crystal Tower,’ as Eggleston calls it – a circular, high-domed space lined almost entirely with intricate glass and mirror work, which were hand made by an Iranian craftsman that Szell had flown in especially. The mirror work, known as ‘ayeneh kari’ in Farsi, is associated with 16th century Safavid-era art, when it was often used to decorate the interiors of Iran’s palaces, shrines and mosques.

The ‘Crystal Tower’ was not only the embassy’s most outstanding architectural feature, according to Eggleston, but also the place that earned the Iranian Embassy some of its reputation for being the most coveted ticket in town.

‘In the middle of the room was a water pipe that stood about five feet high and, more than once after the party was over, the hired help and a few trusted people and so forth would hang around. [That’s when] the real party began…’ Eggleston says.

When the embassy closed in April 1980 – the beginning of the end of diplomatic relations between the US and Iran – Washington would never see those legendary, Iranian-infused nights of glitz and glamour again. ‘It was really depressing,’ says Eggleston. ‘You had something that was such a source of joy to so many people and so much fun, and almost overnight it turned into something like a train wreck.’

Thirty three years after it shut, Iranian-American artist Eric Parnes, who regularly explores the East-West dichotomy in his work, gained unprecedented access to the former Iranian Embassy and took photographs that would become an exhibition titled ‘Custodian of Vacancy: The Iranian Embassy in the USA’ at Dubai’s Ayyam Gallery in 2013.

‘It was like opening up a tomb,’ says Parnes of the moment he walked in. ‘It had this smell… If you’ve ever been to a basement that hasn’t been traversed in a period of time, it had that musky scene attached to it. It was very overwhelming. On top of that, it was dark. It’s not being used and it’s a large space – you can’t help but feel that there’s this sense of vacancy that exists there.’

Though Parnes’ photography portrays this emptiness with photographs of everything from a room full of stacked, dusty dining room chairs to broken glass – presumably from the once glorious ‘Crystal Tower’ – the outer structure of the building is also of significance.

‘It’s very Persian, it’s also very modern,’ Parnes says. ‘It’s like this mid-century Persian structure in the middle of Washington, and for that matter, really, in the middle of the United States.’

Talinn Grigor, an associate professor of modern and contemporary architecture at Brandeis University in Massachusetts, and author of ‘Building Iran: Modernism, Architecture, and National Heritage Under the Pahlavi Monarchs’, says the building, which was built in 1959, straddles traditional Persian architecture with attempts to be modern, too. ‘It has this monumentality, but it’s also democratic,’ she says. ‘It’s trying to establish an Iranian modernity, which is exactly what the Shah was doing in the political realm.’

Grigor believes the architect behind the design of the embassy was Mohsen Foroughi, the renowned, pioneering Iranian architect who designed the tomb of famous Persian poet Saadi Shirazi in the city of Shiraz, or ‘at the very least someone trained directly by him,’ she says.

The modern and minimalist similarities between the tomb and the façade of the former embassy are hard to dismiss. Several thin granite columns and detailed blue tiling work at the embassy’s entrance are reminiscent of those at the poet’s tomb, as is the blue dome visible from the side of the abandoned building.

Although the Iranian royal seal on the embassy’s doors has now been removed, as have the striking sculptures of bighorn sheep, lion and deer by American sculptor Ulysses Ricci, the building remains distinctively different in both time and space from its Georgian style neighbours lining ‘Embassy Row.’

In 2011, the US State Department reported in a memo that it had provided essential repairs for the embassy to ‘ensure the safety of mechanical, electrical and plumbing systems,’ which also included maintenance of the blue-tiled dome, making it stable and watertight. Although the structure is being maintained, it still sits in a substantial amount of decay accumulated after decades of desertion.

As for renewed diplomatic relations that could see the embassy come back to life, it might be just a matter of time, says Parnes. ‘It’s just a question of “when,” I don’t think it’s a question of “if,”’ he says. ‘They’re protecting it, I believe, in the anticipation that it will be occupied again.’

This article appears in the Brownbook’s latest Design Directory, Embassy Architecture of the Middle East and North Africa.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community