The case is legally dubious and factually challenged.

By Alex Ward 14-June-2019

The Trump administration keeps saying that it doesn’t want to go to war with Iran. The problem is that some top officials continue to make statements that could pave a dubiously legal and factually challenged pathway to war.

If that’s the intention, a major flare-up between Washington and Tehran could lead the administration to say it has the right to launch what would be one of the nastiest, bloodiest conflicts in modern history — even if it really doesn’t legally have that authorization.

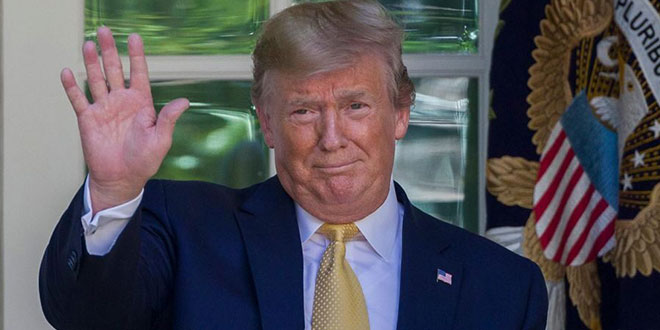

For months, President Donald Trump and some of his top officials have claimed Iran and al-Qaeda, the terrorist group that launched the 9/11 terror attacks, are closely linked. That’s been a common refrain despite evidence showing their ties aren’t strong at all. In fact, even al-Qaeda’s own documents detail the weak connection between the two.

But insisting there’s a nefarious, continual relationship matters greatly. In 2001, Congress passed an Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), allowing the president “to use all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations, or persons he determines planned, authorized, committed, or aided the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001, or harbored such organizations or persons.”

Which means that if the Trump administration truly believes Iran and al-Qaeda have been in cahoots before or after 9/11, then it could claim war with Tehran already is authorized by law.

That chilling possibility was raised during a House Armed Services Committee session early Thursday morning by an unlikely pair: Rep. Matt Gaetz (R-FL), a top Trump ally, and Rep. Elissa Slotkin (D-MI), a Pentagon official in the Obama administration.

“The notion that the administration has never maintained that there are elements of the 2001 AUMF that would authorize their hostilities toward Iran is not consistent with my understanding of what they said to us,” said Gaetz. “We were absolutely presented with a formal presentation on how the AUMF might authorize war on Iran,” added Slotkin right after, although she noted no one said they would use it to greenlight a fight.

It doesn’t help that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, an anti-Iran hardliner, told lawmakers behind closed doors in May that he felt Americans would support a war with Tehran if the US or its allies were attacked, congressional sources familiar with that conversation told me.

The Trump administration already blames Iran for multiple attacks on oil tankers in a strategic Middle Eastern waterway, including two Thursday on Japanese- and Norwegian-owned vessels.

None of this means the US and Iran are going to war anytime soon, or even at all. But it does mean the administration may feel it has the legal basis to do so if it wanted to.

The complicated al-Qaeda-Iran connection, explained

On the surface, al-Qaeda and Iran make an odd pairing. Iran is a Shia Muslim state, and al-Qaeda is a radical Sunni terrorist organization, so it stands to reason that they would have no business interacting with each other.

But it turns out they have worked together before.

Here’s a section from the 9/11 Commission report, the most authoritative account of how the attacks happened and the backstory behind al-Qaeda’s rise:

In late 1991 or 1992, discussions in Sudan between al Qaeda and Iranian operatives led to an informal agreement to cooperate in providing support — even if only training — for actions carried out primarily against Israel and the United States. Not long afterward, senior al Qaeda operatives and trainers traveled to Iran to receive training in explosives. In the fall of 1993, another such delegation went to the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon for further training in explosives as well as in intelligence and security. Bin Ladin reportedly showed particular interest in learning how to use truck bombs such as the one that killed 241 U.S. Marines in Lebanon in 1983. The relationship between al Qaeda and Iran demonstrated that Sunni-Shia divisions did not necessarily pose an insurmountable barrier to cooperation in terrorist operations.

Iran’s proxy group in Lebanon, Hezbollah, also helped train al-Qaeda operatives ahead of its 1998 bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. In 2003, al-Qaeda killed more than 30 people in Saudi Arabia’s capital, Riyadh, and the plotters fled to Iran. Eight years later, the Obama administration said there was a “secret deal” between Iran and al-Qaeda “to funnel funds and operatives through its territory.”

The US government maintains that Iran and al-Qaeda remain linked in that way. Take this, from a 2012 State Department report: Iran “allowed AQ [al-Qaeda] members to operate a core facilitation pipeline through Iranian territory, enabling AQ to carry funds and move facilitators and operatives to South Asia and elsewhere.” A nearly identical passage exists in the latest version of the annual report from 2018, although that one specifically mentions “Syria” as a destination for the “facilitators and operatives.”

Those kinds of statements have led some experts to say the AUMF can be invoked to approve a war with Tehran. “If the facts show Iran or any other nation is harboring al Qaeda, that’s a circumstance which would make the argument for the applicability of the 2001 AUMF quite strong,” retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Charles Dunlap Jr., now at Duke University, told the Washington Times in February.

But there’s also a lot of evidence showing that Iran and al-Qaeda aren’t all that close and, crucially, haven’t colluded to commit terrorist attacks.

Just weeks after 9/11, then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad falsely accused the US of having organized and carried out the attacks. Al-Qaeda wasn’t pleased: “Why would Iran ascribe to such a ridiculous belief that stands in the face of all logic and evidence?” the terror group wrote in its English-language magazine Inspire. “Al Qaeda … succeeded in what Iran couldn’t.”

A 2018 study by the New America think tank, based on roughly 470,000 declassified filesobtained from Osama bin Laden’s Pakistan compound in 2011, showed no links between Iran and al-Qaeda to commit terrorist acts. “In none of these documents did I find references pointing to collaboration between al-Qaeda and Iran to carry out terrorism,” Nelly Lahoud, the study’s author, wrote in a blog post last September.

What the documents do show is that Tehran was deeply uncomfortable having al-Qaeda on its soil, and that bin Laden fiercely distrusted Iran.

For example, Iran detained al-Qaeda members — and some in bin Laden’s family — for abusing the conditions of their stay in the country. An al-Qaeda operative thought Tehran was keeping some of its members hostage: “Iranian authorities decided to keep our brothers as a bargaining chip” after the US invaded Iraq in 2003, a document reviewed in the study read.

In other words, Iran wasn’t holding al-Qaeda operatives just for fun; it was doing so as a way to possibly strike a deal with America down the line.

It turns out that Iran and al-Qaeda actually have been at odds for a long time.

“From his safe house in Abbottabad, Osama bin Laden considered Iran’s increasing regional footprint to be a menace and weighed plans to counter it,” Thomas Jocelyn, an Iran expert at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies in Washington, wrote in the Weekly Standard last year. “Al Qaeda’s branches have also fought Iranian proxies, including Hezbollah fighters, on the ground in Syria and Yemen for years. Anti-Iranian rhetoric is a regular feature of al Qaeda’s propaganda and other statements.”

The question, then, is what one makes of this history. Does it mean that Iran should be forever linked with al-Qaeda? Or is it removed enough from the Sunni group that Iran isn’t covered in the AUMF?

The Trump administration clearly believes the former — but Congress just as clearly doesn’t.

Trump faces stiff resistance against using the AUMF for an Iran war

When Trump withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, he started off his announcement with a striking statement.

“The Iranian regime is the leading state sponsor of terror. It exports dangerous missiles, fuels conflicts across the Middle East, and supports terrorist proxies and militias such as Hezbollah, Hamas, the Taliban, and al Qaeda,” he said.

It’s an argument the administration continues to push.

In April, Pompeo told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that “there is no doubt there is a connection between the Islamic Republic of Iran and al-Qaeda. Period. Full stop.” He continued: “They have hosted al-Qaeda. They have permitted al-Qaeda to transit their country.”

When pressed by Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) if he thought the 2001 AUMF applied to Iran, Pompeo refused to answer the question, saying he’d “rather leave that to lawyers.”

Also in April, the administration labeled Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, Iran’s hugely influential security and military organization responsible for the protection and survival of the regime, as a “foreign terrorist organization.” That means if evidence surfaced of IRGC members working with al-Qaeda operatives, it’d be easier to say a terror group is aiding another terror group.

And in the same Thursday speech in which Pompeo blamed Iran for attacks on two oil tankers this week, he listed off a series of assaults he said were “instigated by the Islamic Republic of Iran and its surrogates against American and allied interests.” One of them was a May 31 car bombing in Afghanistan that slightly wounded four US troops and killed Afghan civilians. The Taliban, which controlled Afghanistan and harbored al-Qaeda prior to the 9/11 attacks, took responsibility for the bombing.

Pompeo thus linked Iran with the Taliban’s plot without providing any evidence. It’s unclear why he did that, but some — like Sen. Bernie Sanders’s (I-VT) foreign policy adviser Matthew Duss— say the secretary wanted to build a case that the 2001 AUMF covers Iran.

Lawmakers from both parties in Congress, though, have staunchly pushed back against the administration’s argument. Sens. Tom Udall (D-NM) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) put forward an amendment to this year’s must-pass defense bill requiring an entirely new AUMF to approve a war with Iran. Rep. Mac Thornberry (R-TX), the top Republican on the House Armed Services Committee, also has said the 2001 AUMF doesn’t apply to Iran.

Others have also come out asking the administration to reconsider its position.

It’s worth reiterating that the administration continually says it doesn’t seek a war with Iran. Instead, officials claim it has applied immense economic pressure on the Islamic Republic solely in hopes of bringing it to the negotiating table — not as a prelude to conflict.

But if the administration changes its mind and decides war is necessary, it’s possible Trump’s team could use the AUMF to launch a strike — and it would be fair to consider that an illegal attack.

It doesn’t help that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, an anti-Iran hardliner, told lawmakers behind closed doors in May that he felt Americans would support a war with Tehran if the US or its allies were attacked, congressional sources familiar with that conversation told me.

The Trump administration already blames Iran for multiple attacks on oil tankers in a strategic Middle Eastern waterway, including two Thursday on Japanese- and Norwegian-owned vessels.

None of this means the US and Iran are going to war anytime soon, or even at all. But it does mean the administration may feel it has the legal basis to do so if it wanted to.

The complicated al-Qaeda-Iran connection, explained

On the surface, al-Qaeda and Iran make an odd pairing. Iran is a Shia Muslim state, and al-Qaeda is a radical Sunni terrorist organization, so it stands to reason that they would have no business interacting with each other.

But it turns out they have worked together before.

Here’s a section from the 9/11 Commission report, the most authoritative account of how the attacks happened and the backstory behind al-Qaeda’s rise:

In late 1991 or 1992, discussions in Sudan between al Qaeda and Iranian operatives led to an informal agreement to cooperate in providing support — even if only training — for actions carried out primarily against Israel and the United States. Not long afterward, senior al Qaeda operatives and trainers traveled to Iran to receive training in explosives. In the fall of 1993, another such delegation went to the Bekaa Valley in Lebanon for further training in explosives as well as in intelligence and security. Bin Ladin reportedly showed particular interest in learning how to use truck bombs such as the one that killed 241 U.S. Marines in Lebanon in 1983. The relationship between al Qaeda and Iran demonstrated that Sunni-Shia divisions did not necessarily pose an insurmountable barrier to cooperation in terrorist operations.

Iran’s proxy group in Lebanon, Hezbollah, also helped train al-Qaeda operatives ahead of its 1998 bombings of US embassies in Kenya and Tanzania. In 2003, al-Qaeda killed more than 30 people in Saudi Arabia’s capital, Riyadh, and the plotters fled to Iran. Eight years later, the Obama administration said there was a “secret deal” between Iran and al-Qaeda “to funnel funds and operatives through its territory.”

The US government maintains that Iran and al-Qaeda remain linked in that way. Take this, from a 2012 State Department report: Iran “allowed AQ [al-Qaeda] members to operate a core facilitation pipeline through Iranian territory, enabling AQ to carry funds and move facilitators and operatives to South Asia and elsewhere.” A nearly identical passage exists in the latest version of the annual report from 2018, although that one specifically mentions “Syria” as a destination for the “facilitators and operatives.”

Those kinds of statements have led some experts to say the AUMF can be invoked to approve a war with Tehran. “If the facts show Iran or any other nation is harboring al Qaeda, that’s a circumstance which would make the argument for the applicability of the 2001 AUMF quite strong,” retired Air Force Maj. Gen. Charles Dunlap Jr., now at Duke University, told the Washington Times in February.

But there’s also a lot of evidence showing that Iran and al-Qaeda aren’t all that close and, crucially, haven’t colluded to commit terrorist attacks.

Just weeks after 9/11, then-Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad falsely accused the US of having organized and carried out the attacks. Al-Qaeda wasn’t pleased: “Why would Iran ascribe to such a ridiculous belief that stands in the face of all logic and evidence?” the terror group wrote in its English-language magazine Inspire. “Al Qaeda … succeeded in what Iran couldn’t.”

A 2018 study by the New America think tank, based on roughly 470,000 declassified filesobtained from Osama bin Laden’s Pakistan compound in 2011, showed no links between Iran and al-Qaeda to commit terrorist acts. “In none of these documents did I find references pointing to collaboration between al-Qaeda and Iran to carry out terrorism,” Nelly Lahoud, the study’s author, wrote in a blog post last September.

What the documents do show is that Tehran was deeply uncomfortable having al-Qaeda on its soil, and that bin Laden fiercely distrusted Iran.

For example, Iran detained al-Qaeda members — and some in bin Laden’s family — for abusing the conditions of their stay in the country. An al-Qaeda operative thought Tehran was keeping some of its members hostage: “Iranian authorities decided to keep our brothers as a bargaining chip” after the US invaded Iraq in 2003, a document reviewed in the study read.

In other words, Iran wasn’t holding al-Qaeda operatives just for fun; it was doing so as a way to possibly strike a deal with America down the line.

It turns out that Iran and al-Qaeda actually have been at odds for a long time.

“From his safe house in Abbottabad, Osama bin Laden considered Iran’s increasing regional footprint to be a menace and weighed plans to counter it,” Thomas Jocelyn, an Iran expert at the Foundation for the Defense of Democracies in Washington, wrote in the Weekly Standard last year. “Al Qaeda’s branches have also fought Iranian proxies, including Hezbollah fighters, on the ground in Syria and Yemen for years. Anti-Iranian rhetoric is a regular feature of al Qaeda’s propaganda and other statements.”

The question, then, is what one makes of this history. Does it mean that Iran should be forever linked with al-Qaeda? Or is it removed enough from the Sunni group that Iran isn’t covered in the AUMF?

The Trump administration clearly believes the former — but Congress just as clearly doesn’t.

Trump faces stiff resistance against using the AUMF for an Iran war

When Trump withdrew the US from the Iran nuclear deal in May 2018, he started off his announcement with a striking statement.

“The Iranian regime is the leading state sponsor of terror. It exports dangerous missiles, fuels conflicts across the Middle East, and supports terrorist proxies and militias such as Hezbollah, Hamas, the Taliban, and al Qaeda,” he said.

It’s an argument the administration continues to push.

In April, Pompeo told the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that “there is no doubt there is a connection between the Islamic Republic of Iran and al-Qaeda. Period. Full stop.” He continued: “They have hosted al-Qaeda. They have permitted al-Qaeda to transit their country.”

When pressed by Sen. Rand Paul (R-KY) if he thought the 2001 AUMF applied to Iran, Pompeo refused to answer the question, saying he’d “rather leave that to lawyers.”

Also in April, the administration labeled Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps, Iran’s hugely influential security and military organization responsible for the protection and survival of the regime, as a “foreign terrorist organization.” That means if evidence surfaced of IRGC members working with al-Qaeda operatives, it’d be easier to say a terror group is aiding another terror group.

And in the same Thursday speech in which Pompeo blamed Iran for attacks on two oil tankers this week, he listed off a series of assaults he said were “instigated by the Islamic Republic of Iran and its surrogates against American and allied interests.” One of them was a May 31 car bombing in Afghanistan that slightly wounded four US troops and killed Afghan civilians. The Taliban, which controlled Afghanistan and harbored al-Qaeda prior to the 9/11 attacks, took responsibility for the bombing.

Pompeo thus linked Iran with the Taliban’s plot without providing any evidence. It’s unclear why he did that, but some — like Sen. Bernie Sanders’s (I-VT) foreign policy adviser Matthew Duss— say the secretary wanted to build a case that the 2001 AUMF covers Iran.

Lawmakers from both parties in Congress, though, have staunchly pushed back against the administration’s argument. Sens. Tom Udall (D-NM) and Tim Kaine (D-VA) put forward an amendment to this year’s must-pass defense bill requiring an entirely new AUMF to approve a war with Iran. Rep. Mac Thornberry (R-TX), the top Republican on the House Armed Services Committee, also has said the 2001 AUMF doesn’t apply to Iran.

Others have also come out asking the administration to reconsider its position.

It’s worth reiterating that the administration continually says it doesn’t seek a war with Iran. Instead, officials claim it has applied immense economic pressure on the Islamic Republic solely in hopes of bringing it to the negotiating table — not as a prelude to conflict.

But if the administration changes its mind and decides war is necessary, it’s possible Trump’s team could use the AUMF to launch a strike — and it would be fair to consider that an illegal attack.

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community