By Ishaan Tharoor

President Trump’s reintroduction of sanctions on Iran isn’t going over well with the international community. On Wednesday, the United Nations’ highest court ordered the United States to remove any restrictions on the export of humanitarian goods and services to Iran.

Iranian officials had appealed to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague, arguing that Trump’s move to pull out of the nuclear deal with Iran and reimpose sanctions violated, among other things, a 1955 Treaty of Amity between the two countries. The court didn’t give Iran the sweeping ruling against all sanctions that it hoped, but enough to claim a moral victory.

But the ICJ doesn’t have the power to enforce its rulings, and the Trump administration wasn’t about to let foreign judges constrain its actions. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo quickly announced that the United States was withdrawing from the Treaty of Amity. Iran, he said, had been violating it “for an awfully long time,” anyway.

Then, at a White House briefing, national security adviser John Bolton announced that the administration was reviewing all agreements that could subject the United States to future rulings by the court. He said Washington would withdraw from an amendment to the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations, an “optional protocol” that allowed Palestinian officials to file a suit against the United States at the ICJ last week for moving its embassy in Israel to Jerusalem.

“The United States will not sit idly by as baseless politicized claims are brought against us,” Bolton said. When asked about Tehran’s response, he replied that “Iran is a rogue regime . . . so I don’t take what they say seriously at all.”

But other governments still do. During meetings at the United Nations last week, Trump, Pompeo and Bolton railed against Iran and berated various other member states and U.N. bodies for not bending to American interests. Their approach elicited an icy reaction. At a Security Council session chaired by President Trump, every other member of the U.N.’s most powerful body scolded Washington for its rejection of the nuclear deal, an agreement the council had endorsed.

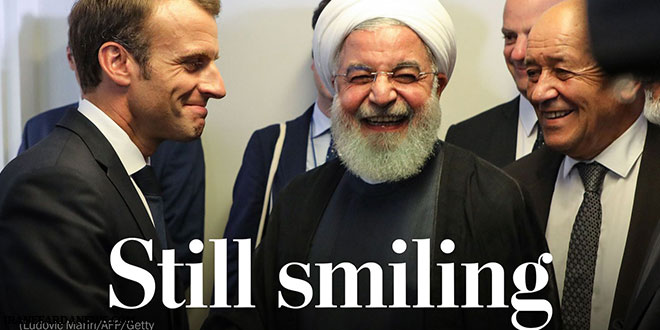

Iran’s political leadership is enjoying its moment of international solidarity. After the ICJ ruling, Foreign Minister Javad Zarif termed the United States an “outlaw regime” in pursuit of a “malign” agenda, parroting U.S. attacks on Tehran. Meanwhile, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani welcomed a European proposal to create a barter system in which companies could trade with Iran without money changing hands, thus skirting U.S. sanctions. “Europe has taken a big step,” he said.

Iran hopes that the ICJ’s announcement, though mostly symbolic, will give a similar boost to its trade prospects. “The decision could encourage European companies, which ceased trading with Iran for fear of falling foul of President Trump, to reconsider their position, specifically those dealing in the humanitarian items outlined by the judges,” wrote Anna Holligan, the BBC’s correspondent in The Hague.

Away from the chambers of U.N. organizations, however, the picture is a bit gloomier for Tehran. Iran’s financial sector has long been a mess. Its currency, the rial, has lost about 70 percent of its value since May. One analysis by a group of economists forecasts that the country’s economy could contract close to 4 percent in 2019 — a collapse driven largely by the reimposition of oil sanctions, which will come into place next month.

“The pressures will have an impact and put [the Trump administration] in position to claim credit for things that would have happened anyway,” said Patrick Clawson, director of research at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, speaking at a panel on Iran held by the Center for the National Interest in Washington.

Trump and the anti-Iran ideologues in his administration have cited the difficulties faced by the regime — as well as the economic protests that have flared up in various parts of the country — as evidence of a nation ready for real political change. They believe the sanctions will galvanize the Iranian opposition and force the country’s leaders to curb their support for their armed proxies across the Middle East.

But some analysts fear the sanctions will have the opposite effect. Figures such as Rouhani and Zarif have drawn popular ire over the country’s economic mismanagement, but they don’t make the final decisions on Iran’s military footprint abroad. The theocratic regime’s hardliners, particularly among its Revolutionary Guard Corps, control that portfolio. And with recent polling suggesting that Iranians still largely support their country’s foreign policy, the mullahs have little incentive to change course.

“We have altered the trajectory of the Islamic Republic, but not in a good way,” said Barbara Slavin of the Atlantic Council, speaking at the same event. She pointed to the surging popularity of Qassem Soleimani, a key leader within the IRGC, whose foreign proxies are engaged in conflicts in Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

“I thought that an Iran that was more engaged with the world would be one that would be more likely to evolve in a more liberal direction,” Slavin said, referring to the hopes of many people who backed the nuclear deal. “Now the military will become stronger.”

Key U.S. allies also fear the dangers of Trump’s path. Speaking with reporters in Washington on Wednesday, Ahmed Mahjoub, Iraq’s chief foreign-affairs spokesman, warned that sanctions will hurt ordinary Iraqis, who are vulnerable to economic chaos next door.

He pointed out the failures of U.S. sanctions imposed on the government of Saddam Hussein in the 1990s. Sanctions “do harm to the people, not the political regime,” he said. “Imposing them is futile and will hurt Iranians who may otherwise be sympathetic to the United States.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community