By JAMES KITFIELD

Who are Trump’s generals? Yesterday, James Kitfield told us what these retired soldiers have in common as products of our post-9/11 wars. Now we’ll go deep into the formative experiences and geopolitical worldview of each man, starting today with the prospective Secretary of Defense, Gen. Jim Mattis. He’s been nicknamed both “Mad Dog” and “Warrior Monk,” but which one is the real Jim Mattis?

Navy sailors captured by Iran in the Persian Gulf

When General Mattis served as the commander of US Central Command in 2013, he took responsibility for a region on fire. The Taliban and Al Qaeda continued to use sanctuaries in Pakistan to destabilize neighboring Afghanistan, where US troops were still fighting. The Syrian civil war was destabilizing its neighbors such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey with unprecedented flows of refugees, and attracting like moths to a flame Islamist extremist groups such as ISIS and the al-Nusra Front. The sectarian rule of Iraqi Prime Minister and Shiite Nouri al-Maliki was threatening to reignite a Shiite versus Sunni civil war there. Libya had descended into chaos after the NATO intervention that toppled the government of Muammar Gaddafi. Yemen was teetering towards all out civil war following its own Arab Spring revolution that ousted its strongman ruler Ali Abdullah Saleh, a US ally.

And yet when he woke up each morning, Mattis recently said that the first three questions he confronted centered on Iran, Iran and Iran.

“The Iranian regime, in my mind, is the single most enduring threat to stability and peace in the Middle East,” Mattis told an audience at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in April. Al Qaeda and the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria remain immediate and serious threats, he noted, and the Palestinian-Israeli conflict remains a concern. “But nothing, I believe, is as serious in the long term, in terms of its enduring ramifications…as Iran.”

At Odds With Obama

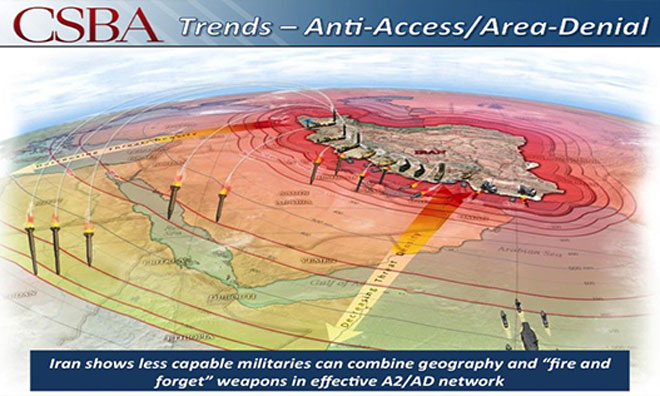

While the rest of the Obama foreign affairs team was focused on reaching a long-sought deal to curtail Iran’s nuclear weapons program, Mattis was monitoring the threat Iran continued to pose in other realms such as maritime security in the Persian Gulf, ballistic missile development and proliferation, cyber insecurity, and, especially, state-sponsored terrorism. With the money Iran has received from the unfreezing of its funds and the relaxation of sanctions as part of the nuclear deal, Mattis believes Iran will invest heavily in those other destabilizing activities.

Iranian Basij militia.

A State Department report in 2012 noted that Iran had already increased the tempo of its support for proxies in the region such as Lebanese Hezbollah and Shiite militias in Iraq. US Navy and allied ships continued to interdict Iranian arms shipments to terrorist and insurgent groups in Yemen, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia. Iranian Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani and his colleagues have called for wiping Israel off the map and annexing Bahrain, and they have boasted publicly of Tehran’s control over four regional capitals in Lebanon, Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

Mattis’ tough rhetoric on Iran led to his being ousted early from his job at CENTCOM in 2013. At CSIS he gave a preview of how his perception of the Iranian threat might manifest itself in policy if he is to become Secretary of Defense. Absent a clear violation of the Iran nuclear agreement that the “P5 plus 1” nations (the United States, Britain, France, China, Russia and Germany) signed in 2015, he doesn’t believe there is any “going back” on that deal.

“I believe we would be alone if we did that, and unilateral economic sanctions from the United States would not have anywhere near the impact of an allied approach,” said Mattis. “But I do think we’re going to have to hold at risk Iran’s nuclear program in the future. In other words, make plans now of what we will do if in fact Iran restarts that program.”

A Secretary of Defense Mattis is likely to advocate for a more assertive strategy designed to deter and contain Iran. That strategy would begin with firmer commitments to nervous allies in the region such as Jordan, the United Arab Emirates, and Saudi Arabia. Other likely elements of a Mattis strategy for the Middle East that he sketched out at CSIS include

stepped-up arms sales to regional allies such as Saudi Arabia, which recently surpassed Russia as the third largest spender on military weapons;

a sharper focus on Iran by a beefed up intelligence community that can use the nuclear deal’s stringent verification regime to develop targets in the event Iran cheats or restarts its nuclear weapons program;

a more capable and integrated allied missile defense system in the region;

a restart of “Radio Farsi” to beam news and information directly to the Iranian people, much as Voice of America countered Soviet propaganda during the Cold War;

more maritime exercises hosted by the US Navy’s 5th Fleet such as a de-mining drill during Mattis’ tenure at CENTCOM that attracted the navies of 39 nations; and continued US sanctions on Iran for its sponsorship of terrorism.

“We’re going to have to return to a strategic view such as we had years ago, because we now know the vacuums left in the Middle East seem to be filled either by terrorists, Iran and its surrogates, or Russia,” Mattis said. “In the future, we need to recognize that to restore deterrence, [the United States] is going to have to show capability, capacity and resolve.”

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community

khalijefars News, Blogs, Art and Community